Nothing is certain except death and taxes, the saying goes — but there’s another sure thing to add to that list: change.

“The more we resist change, the more we suffer. There’s a phrase I like. It says, ‘Let go or be dragged,’” said Robert Waldinger, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the director of the Harvard Study on Adult Development, one of the longest-running studies on human happiness and well-being.

As humans, we are constantly changing. Sometimes change is pursued intentionally, when we set goals, for example. But change also happens subconsciously, and not always for the better. Richard Weissbourd, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and director of Making Caring Common, said that disillusionment is often underappreciated as a factor in change.

“People can respond to disillusionment by becoming bitter and withdrawing — and cynical,” he said. “They can also respond to disillusionment by developing a more encompassing understanding of reality and thriving.”

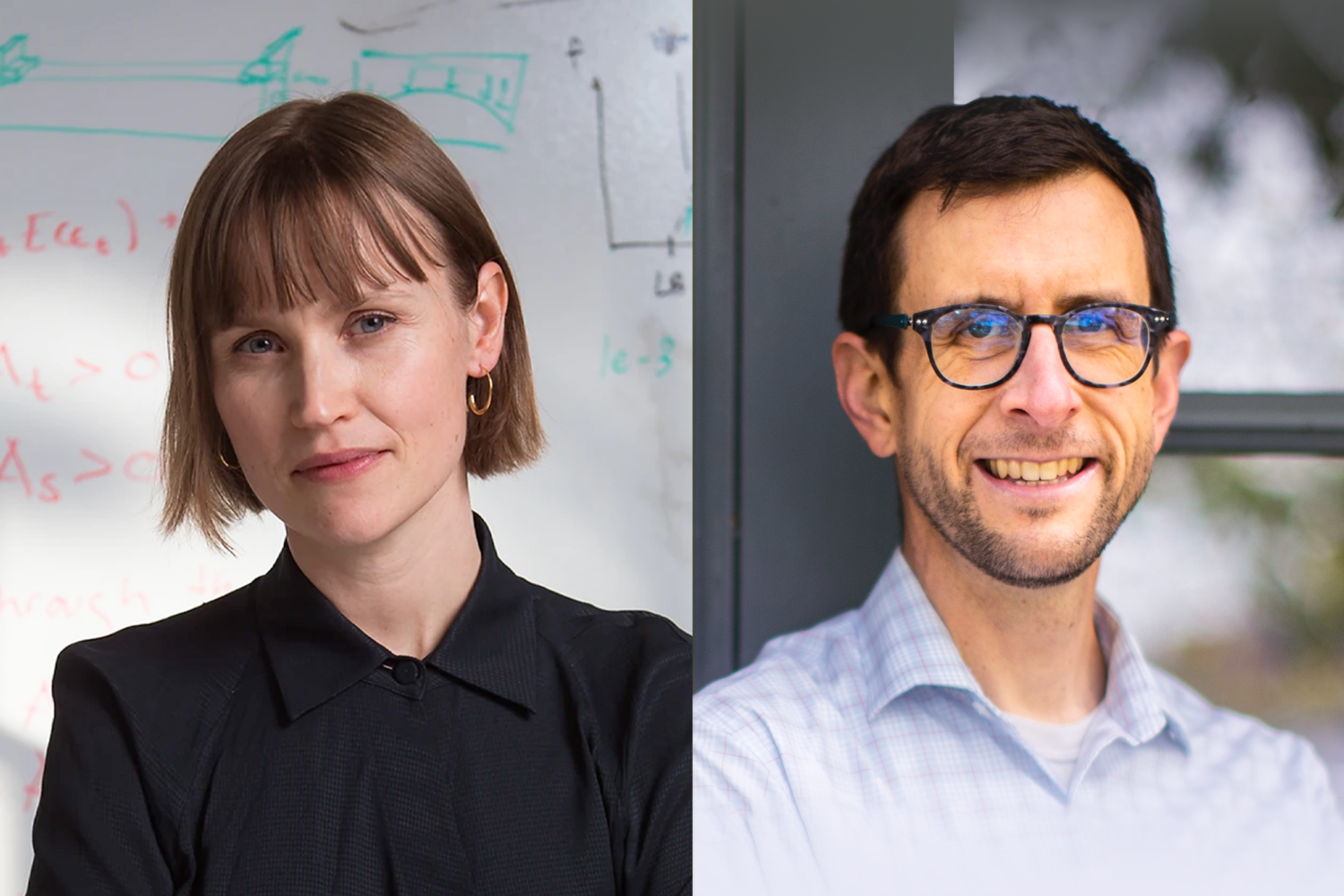

In this episode of “Harvard Thinking,” host Samantha Laine Perfas talks with Waldinger, Weissbourd, and Banaji about the value of embracing change.

Transcript

Robert Waldinger: The more we resist change, the more we suffer. There’s a phrase I like. It says, “Let go or be dragged.” There is just constant movement of the universe and all of us as individuals as part of the universe.

Samantha Laine Perfas: You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, goes the saying, and sometimes this feels true. But the idea that people can’t change is a myth. Research shows that people are capable of making dramatic shifts at nearly every stage of life in spite of our habits and biases.

So how much of that change is within our control and how much is at the mercy of our circumstances?

Welcome to “Harvard Thinking,” a podcast where the life of the mind meets everyday life. Today, we’re joined by:

Mahzarin Banaji: Mahzarin Banaji. I’m an experimental psychologist. I live and work in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University.

Laine Perfas: Her work focuses on implicit bias, and she co-wrote the best-seller “Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People.” Next:

Waldinger: Bob Waldinger. I’m professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School

Laine Perfas: He also directs the Harvard Study on Adult Development, one of the longest-running studies on human happiness and well-being. It tracks the lives of participants over 80 years. And finally:

Richard Weissbourd: Rick Weissbourd. I’m a senior lecturer at the Grad School of Education. I’ve also taught at the Kennedy School of Government for many years.

Laine Perfas: He’s a psychologist and is the director of the Making Caring Common Project at GSE.

And I’m Samantha Laine Perfas, your host, and a writer for The Harvard Gazette. Today, we’ll discuss how, when, and why we change, intentionally and otherwise.

It feels like we live in a culture that is constantly pushing us to do more, be more. Why do we focus on changing ourselves so much?

Waldinger: What’s so striking is that for a long time, developmental scientists focused almost exclusively on children, because children change so dramatically, right before our eyes. And people thought once we got into our 20s, we found work, if we were lucky we found love, and then we were good to go, we were set, and people didn’t change much across adulthood. People began to look more closely and look at their own experience and realize how much change happens psychologically and biologically across the adult lifespan. And so you began to see the kinds of studies of change across adulthood that my study represents that was begun in 1938. But for a long time, adult development was the kind of poor stepchild of developmental science.

Banaji: Psychologists, I think, have been remiss in really studying the two ends of life, right? As Bob said, because we are interested in development for a variety of reasons, we focus on from the day a baby is born and we go through, really, well, the adolescent years because we’re interested in the emotional mind and what happens, the volatility during adolescence, and change and so on. And then we know nothing until again, we get to a much older age where we worry and think about the last decade of life. But every decade we’re changing. We’re entirely different people.

Weissbourd: There’s so many different domains of change, right? And I think we do have a pretty strong belief in our culture that we can become more effective or competent, that we can become happier. There’s a billion-dollar self-help industry out there that is trying to make people feel better.

My work is primarily on moral development, and I don’t think we have strong notions of change in adult life, and that’s a real problem. There’s a notion in many parts of the country that you’re born good or bad, and you’re going to be good or bad your whole life, and I think we’d be a much healthier culture if we saw ourselves as having the capacity to love other people well and more deeply and empathize more deeply. You can have better relationships. And that’s probably the strongest source of happiness we have.

I would just say one other thing, and it’s really partly a question for all of you. But, I think sometimes people don’t think they change because the narrator doesn’t change. Meaning the person, the thing telling the story of their lives doesn’t feel like it changes. And when I ask people about their narrator, do they have the same narrator when they were 8 or 16 or 30 or 50? Most people think the narrator is the same. So if you think of the narrator as the self and the continuity of the self, I think that’s one of the reasons people often think we’re not changing.

Banaji: I’m remembering my good friend Walter Mischel’s theory of personality and this idea that we believe so much that we and other people are largely consistent across different situations. The lovely example that Walter gives is that we meet people in certain roles so we don’t even know the variability of those people. I know the janitor who stops by my office every evening as a janitor, I don’t know him as a father or as a jazz musician or whatever else. These things give us a false sense of continuity. And I think this spills over into feeling change isn’t present or happening when in fact it is. It’s like our skin. I think I’m right that the epidermis, once a month, we have a new skin and even in older people, it’s only a little slower. It’s every two months. But I don’t notice that and that might be an interesting metaphor for us, that something so close to us on our body that we see all the time is going through an entire regeneration every month, but we don’t notice it.

Waldinger: It’s interesting because I think we’re ambivalent about change, that the mind in many ways craves permanence. Rick, as you’re saying, we have this sense of the narrator being the same narrator when I was 8 years old and now when I’m in my 70s, and of course that’s absurd. I’m a Zen practitioner, and the core teachings of Zen and Buddhism is that the self is a fiction. It’s a helpful fiction that we construct to get through the world, but it’s actually fictitious, and constantly changing. But at the same time, as we want permanence, we want something fixed, we say, “Oh, I want to improve.” And so we get on this endless treadmill of self-improvement. So we really have quite a complex relationship with the idea of change, we human beings.

Weissbourd: I’m one of those people who do have a strong sense of self-sameness, that I am the same person when I was 8. Is that not true for you?

Waldinger: When I was 8, I really thought I could be Superman; and I had a cape and I had a Superman outfit, and I ran around and I jumped on and off my bed. I don’t do that anymore, Rick.

Laine Perfas: Maybe you should. Sounds like a great Saturday afternoon.

Banaji: You know, there’s a lovely piece that Robert Sapolsky, the neurobiologist, wrote, in, I think it was in the ’80s. I remember reading it and smiling because I was still in my 20s. And he said something like, “My research assistant colors his hair purple one week and green the other week. He listens to classical music and pop. He eats regular foods and weird foods.” And he said, “Look at me, I’ve had the same shoulder-length ponytail for the last 40 years and I only listen to reggae and so on.” And he concluded that piece by saying if you haven’t changed by a certain age for certain things, you never will. If you haven’t eaten sushi by the age of 22, you never will. If you haven’t had your nose pierced by 17, you never will. So there are certain things that, yes, it feels that way, but maybe there are bigger changes that happen later in life.

Waldinger: One thing that I’ve been impressed by as I study people getting older is that the big change is in our perception of the finiteness of life. That we all know we’re going to die from a pretty young age, but most of us say, “Ah, it’s way in the future” or “I’m going to be the exception here. I won’t die. Everybody else will.” And then what Laura Carstensen’s work shows, and many people’s, is that in about our mid-40s, we really begin to get a more visceral sense of the finiteness of life and that sense of our mortality increases from the mid-40s onward. You can document it pretty precisely and that institutes a whole set of shifts in how we see ourselves, how we see this narrator moving through the world, and how we see our time horizon. There are some things that are going to change just because of the fact of death.

Laine Perfas: It does seem like some people are very open to change, and they’re constantly learning and growing, But then there are other people who are very comfortable with how they are, even if other people maybe think they should change. It makes me wonder, are there some people who are more susceptible to change than others, or more open to it?

Banaji: As with almost any other psychological physical property, yes, there are individual differences and far be it for me to bring up anything political in this moment. But one of the differences between what we consider to be liberal versus conservative, the dictionary definition, is that one group looks forward and wants change and wants to leave behind old ways of doing things. And the other wants tradition and stability. There’s nothing good or bad here. These are both forces. But this is a real difference, I think, in almost every culture. I was born and raised in India, I’ve lived most of my adult life here, and in both cultures, I’ve seen these two big movements pull and push in opposite directions. And I guess at some level, I’d like to think theoretically that it’s good to have a bit of that pull and push.

Waldinger: And as I understand it, there’s some theory and some grounding in empirical data that some of this may be biologically based, that some of us are temperamentally more inclined to resist change. We humans are arrayed on a spectrum, perhaps even biologically, about how much we welcome versus resist change.

Banaji: I can’t help but mention my colleague Jerry Kagan. Jerry’s notion of temperament in early childhood, he had this view that there were certain personality dimensions that are biologically present in early childhood. And I really believe that some of those very much link up to what you’re saying, Bob. So for example, I have a sister who was very shy, anxious, would hold my little frock and hang behind me. And I was so extroverted that at age 6, I wanted to leave home and go off somewhere else. And I feel that this difference in shyness or anxiety or whatever you want to call it, has played a role in our political beliefs. I am open to new experiences. I meet very different people and packed a bag at 21 and with $40 in my pocket took off without knowing anybody in this country. She wouldn’t leave home without thinking for three hours about what she’s going to do. And this does lead to very different outcomes.

Weissbourd: Yeah, there’s some people who are temperamentally very risk-averse and there are other people who are risk junkies.

Laine Perfas: It is worth mentioning, you know, not all change that we experience is desirable or beneficial. You know, if we encounter trauma or negative experiences, if you’ve been in a really bad breakup and the experience leaves you cynical and love-averse. When we’re going through life and we’re experiencing negative experiences that might push us to change ourselves in ways that might be more harmful or cause us to withdraw, how do we wrestle with that tension versus still being open to the world, not really knowing what might happen?

Waldinger: A lot of my clinical work is psychotherapy. That’s my specialty; actually, I still, every day, I see a couple of people in psychotherapy. And what you see is tremendous variability in people’s willingness, interest in, and ability to make internal shifts in how they see the world and how they experience themselves. And some of that, Sam, is based on what you’re describing, which is some people have had negative experiences that seem to have really baked in certain ways of experiencing themselves in the world and certain expectations of the world and of people as being reliable or not reliable, as being intentionally harmful or basically good.

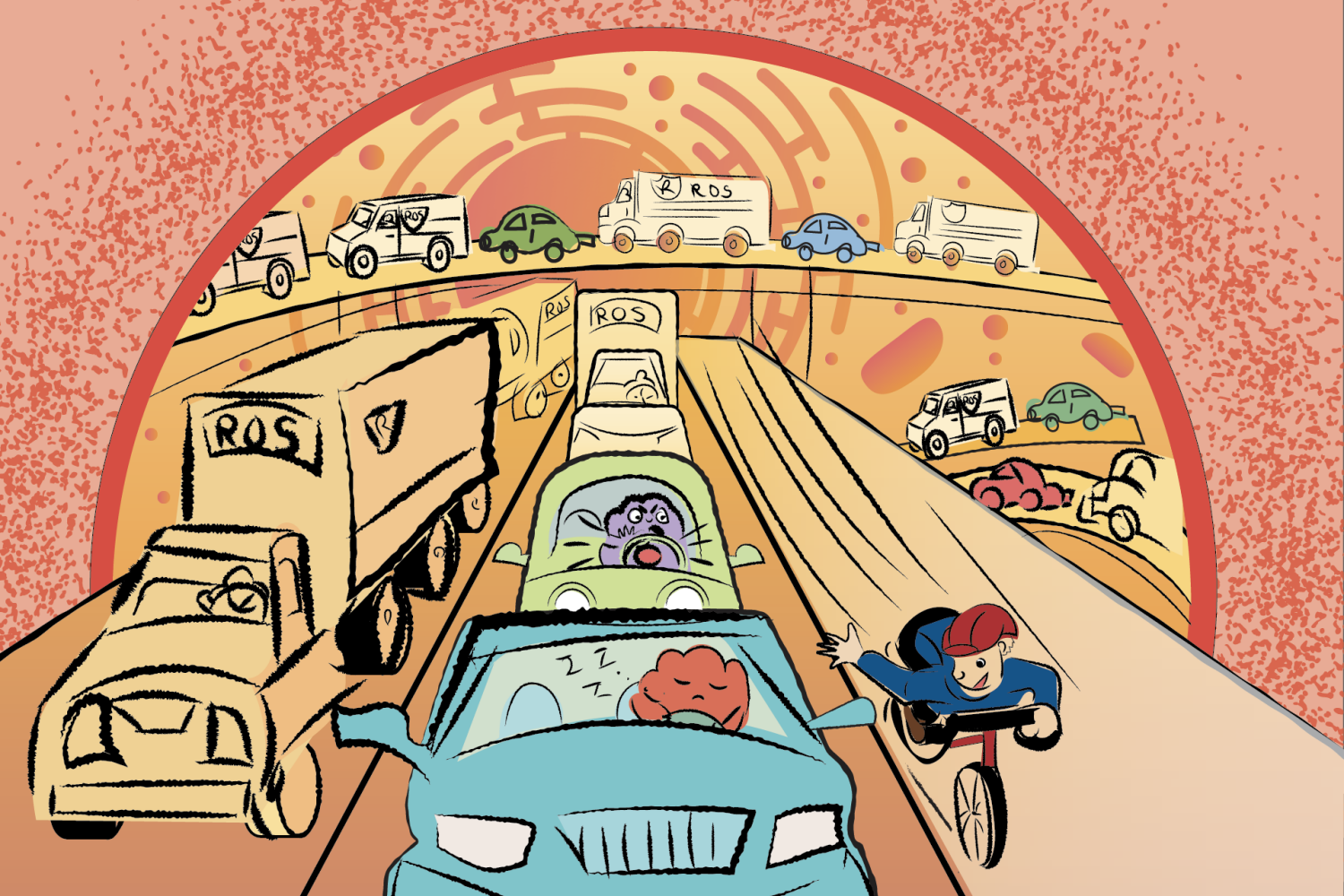

Weissbourd: I would say that most of us experience disillusionment at some point in our lives. My dissertation was on the disillusionment of Vietnam veterans, but I think it’s a very common experience. And I think people can respond to disillusionment by becoming bitter and withdrawing and cynical. They can also respond to disillusionment by developing a more encompassing understanding of reality and thriving, flourishing in the world. We have huge literatures on grief and trauma and depression. We don’t really talk enough about disillusionment, and I think it’s a powerful experience for a lot of people.

Banaji: My colleague Steve Pinker is very fond of pointing out to us something that I think is true, that we may think that we are not changing for the good, but whether you look at women’s rights, whether you look at homicide rates, unemployment, other measures of the economy, happiness — if you take even a 20-year view on most of them, there’s improvement. If you take a 100- or 200-year view, there’s no question that there’s a lot of improvement. Yes, there are pockets where things are getting worse. I’ll put climate in that box and make sure that we don’t forget that. But on many of these things, we are improving. And I come from a country that got independence in ’47, and the remarkable changes I’ve seen over the course of my lifetime in India are just mind-boggling. But our aspirations, I think, for better, which is a very good thing, I think often lead us to not see real progress that has also been made.

Waldinger: And to your point, our cognitive bias that’s built in, our bias to pay more attention to what’s negative and to remember what’s negative longer than what’s positive. When we’re younger, that changes as we get older, but that cognitive bias makes us vulnerable to having this sense that everything’s falling apart and inflamed.

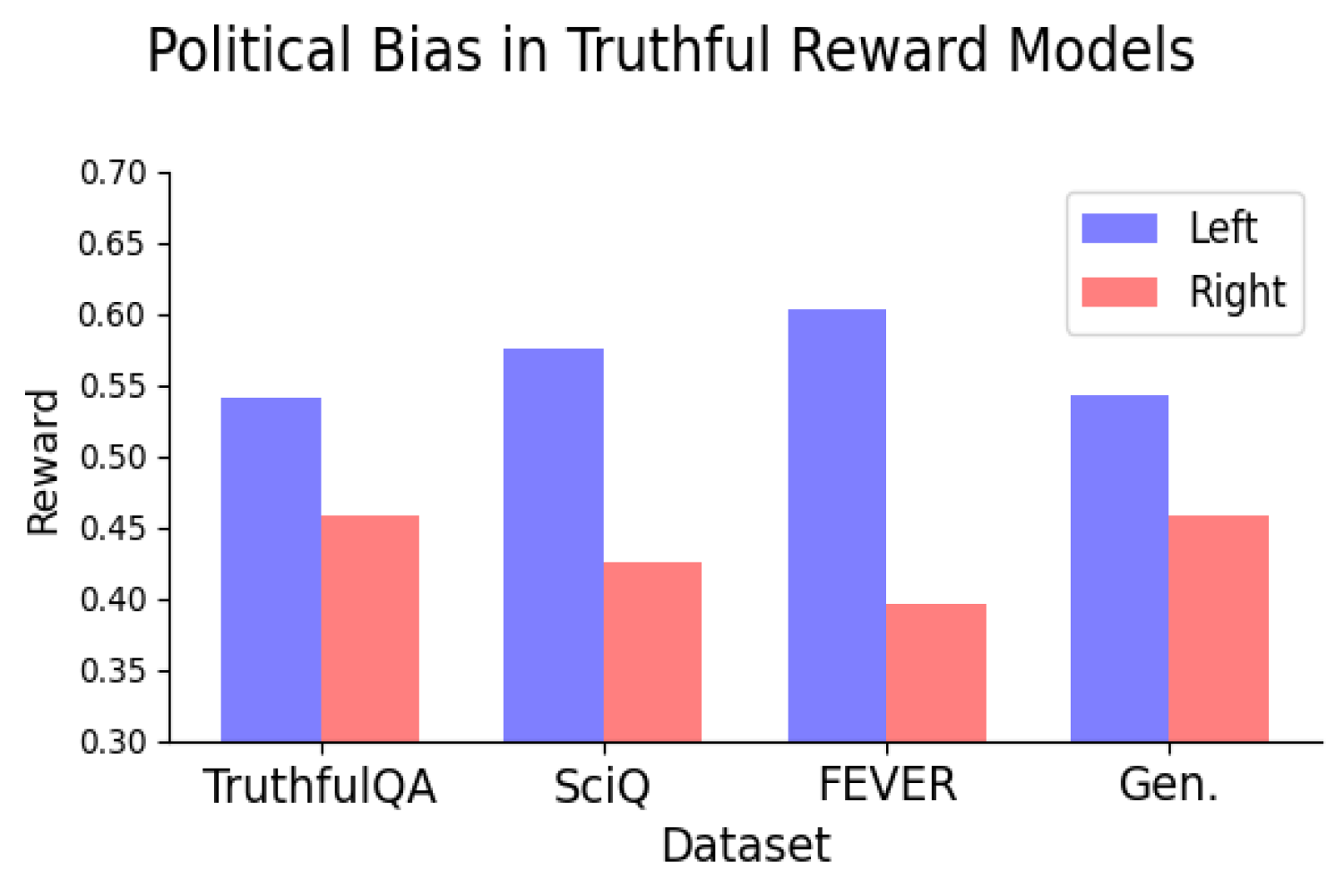

Banaji: I myself showed that bias. When we began to do research on implicit bias, I said to my students, don’t even bother looking for change in it. It’s not going to change. It’s implicit. It’s not controllable. That’s the nature of this beast. We can focus on changing people’s conscious attitudes, but this thing is not going to change, not in my lifetime, and I was completely and utterly wrong on that because even implicit bias, which is not easy to control, we’ve seen something like a 64 percent drop-off in anti-gay bias in a 14-year period. This alone is mind-boggling. How did our culture change so dramatically? How did we go from being so deeply religiously based, all sorts of social pressures, how did grandparents and parents change? All of this happened in a 14-year period, not just on what we say and the rights we’ve given a group of people, but way deep inside of us, our implicit bias has changed.

Weissbourd: Mahzarin, I love this work you’re doing. I’m wondering if you can answer your own question, though. How did this happen?

Banaji: You know, I have many hypotheses, but being an experimentalist makes it really difficult to test these because it doesn’t lend itself to laboratory tests. I think both of you doing the work you’ve done may have better hypotheses, so I would love to hear what they are, but I have a few. The first one is that sexuality had going for it a very positive feature, and that is that sexuality is embedded in all aspects of our society at all levels. There are gay and straight people and everybody in between on the coasts and in the middle of the country, among the rich and the poor, among the educated and the less-educated. I think that’s one of the reasons. I also think that these biases were based in religion, and I think we are becoming a less religious country. So I think perhaps secularism has a small role to play, but I think primarily we are not segregated by sexuality, the way we are on age, the way we are on race. And so I think that just allows for the possibility of change.

Waldinger: One of the things I’ve been impressed by is how powerful stories are. Personal stories, like my son says he’s gay and then, whoa, I’m rethinking a lot of things. But also some of the stories, many people have talked about the influence of media and stories, shows about gay people. And I think that those emotional connections and those very personal stories move us in ways. It’s often when a senator or a congressperson has someone in their family with a mental illness that finally there’s some movement that lessens some of the national policy stigmatization of mental illness. It’s because people have it in their own lives and see it in their own lives in a way.

Laine Perfas: We’ve been talking about the ways that we pursue change or people are open to change. I want to talk a little bit about the people who do not embrace change and who might even fear it.

Banaji: Think about Brexit and also some of what’s going on in this country around immigration and just how much the fear of the outsider has been easy to evoke. There’s certain fears that are just right below the surface. Thinking about groups. It is one of those that I think is a very powerful and easy way to say we don’t want change because it’s so easy to evoke the idea that these people who are not us are going to take our stuff. Somebody just wrote me a week ago and said, do you think there’s a difference between foreign tourists and immigrants? And I said, yes, tourists give us money and we fear that immigrants will take our money. And of course there is a difference. But even within them, there are words that we use. I think this distinction in the word has gone away. But when I was younger, I remember that the word emigre would often be used to refer to white high-status immigrants. And immigrant would be the word to refer to non-white, poorer people coming to our country. So even there, we distinguish to tell ourselves that they come in different kinds, and one is to be feared and the other not.

Waldinger: We also assign these groups who are not us, we assign them the characteristics that we fear are part of us, and we don’t want any part of. So those other people are greedy, those other people are dirty, whatever epithets we apply are often reflections of what we don’t want in ourselves, and we notice glimmers of in ourselves. And so to resist those outsiders, to resist changes that come from the outside, is also saying I’m not going to let this stuff loose.

Weissbourd: I think change also involves grief sometimes and loss, it means a new way of being and foregoing a way of being that’s been very familiar, and the relationships in an old way of being, that you can change in ways that make it so it’s hard to be close to your high school friends. Or you can change in ways that may threaten your romantic relationship.

Laine Perfas: What I was thinking about as I was listening to all of you talk, it’s a fear of the unknown. If I change in some way, I can’t fully predict what that life for me will look like. If it changes, will I even recognize it anymore? Who am I? Do I belong? Is there still a place for me in this new and different world? And I think sometimes that alone can be enough to be like, maybe I’ll just keep doing what I’m doing. It’s a lot to think about.

Banaji: So you’re right, Sam, in bringing this up, because I’ve been worried about a particular issue. You said people for whom their life may not be what they were expecting it to be or had hoped to be, and I think about the group “men” as going through this. Of course, the world still is male-dominated and so on. We just have to look at the disproportionate number of men in power. But I’ve been worried a lot about men being left behind. As somebody who studies bias, I look for it everywhere, especially in places where we would not think to look. And there is something going on in this country. I don’t know how magnified it is elsewhere. But today, 60 percent of college-going people are women. And very soon it will be 65 percent. I think this is terrible for the country. I really believe that we need to hold this to 50/50. It’s not good for the group, but it’s not good for society. In 20 years, I think we will be in a position where we will really regret not having paid attention to this. And it’s not just going to college. There’s just many shifts that are happening for men, that are not getting attention and that I believe should, and it’s a kind of a change, but it’s seemingly having a negative impact on a particular group.

Waldinger: Could you say a little more about that? To hear you say this is really interesting.

Banaji: There’s a book that was written recently, and I wish I were remembering his name, but the book’s name is “Of Boys and Men.”

Laine Perfas: Richard Reeves.

Banaji: Yes, at the Brookings Institute. That book really changed my thinking. I had been feeling this. I had been noticing it because I teach in a concentration, a major, at Harvard that has been slowly turning much more female. And so I began to worry about it because I wondered like, where are the men? Why aren’t they coming to psychology? So when I was the director of undergraduate studies, I started to just collect some back-of-the-envelope data. I said to my colleagues, I’m very concerned about this. I brought it up once in an APA meeting, this is the American Psychological Association group of chairs of psychology departments. And I was slapped down by men and women who said, sorry, we don’t want to worry about this. I was just stunned that we would say such a thing. What can I say? I just feel that there’s now enough evidence that men are saying they’re feeling they’re being left behind. The data are, certainly for college. Now, I know that college is not the be-all and end-all of life and not everybody needs to go to college and so on. But you and I know that going to college changes your life’s trajectory, the way our society is set up currently. It is a very strong path to success. And we’re taking that away from one group of people. To see this happening deserves some attention, in my opinion.

Laine Perfas: I know we’ve been talking at the society level, so I want to bring it a little bit back to the individual. Is it more common for people to change intentionally and purposefully, like they’re pursuing a change in their own life? Or is it more common that we change subconsciously or just simply because of the life experiences that we have?

Waldinger: I would argue it depends on how much pain we’re in. If you have a motivation to change, a conscious motivation, you’re more likely to take steps that are hard and require persistence. But to do that, if things are good, you’re probably not likely to make conscious, deliberate efforts to change because things are good.

Laine Perfas: That’s really interesting. It makes me think about this pursuit of happiness: I still feel unhappy, therefore I’m motivated to constantly keep changing, even though it never actually makes me happier sometimes.

Weissbourd: That’s the kicker, right? That’s the irony, that all the pursuit of happiness often makes you less happy. I certainly agree with Bob about suffering, but I might land differently on the question, just in the sense that I do feel like we’re always evolving, whether we intend to or not. Early adulthood changes you. Parenthood changes you. Midlife often changes people. Aging changes people. So there are inevitable developmental changes that are happening.

Laine Perfas: I was going to ask if we ever get to a point where it’s good to just accept who we are and how we are and to be OK with where we’re at in life.

Weissbourd: I think we have a lifelong responsibility to shield other people from our flaws.

Banaji: I love how you said that.

Waldinger: I also think there’s a distinction between the responsibility to keep trying to be better, to spare other people our worst aspects. And I totally agree with you, Rick. And on the other side, because I see this as a psychiatrist, is this problem of low self-esteem. The Dalai Lama, when he started having more contact with Westerners, said that one of the most striking things for him was that Westerners are much more commonly beset by low self-esteem and harsh self-criticism, much more than the people he encountered in Eastern cultures. Partly because self-esteem is an issue of self-absorption, particularly low self-esteem. And so I think it’s both. I think that we have a responsibility to be better, but that there is also a path to greater self-acceptance, which makes us much more fun to live with when we talk about other people.

Banaji: I never heard the phrase “self-esteem” until I was 24 and arrived in America. And yet there is a positive side to it that I want to point out, and I think this is true of maybe not even Western culture, but the United States. I think Alexis de Tocqueville said something in his book on “Democracy in America” that America was not a better country than other countries, but it had this magnificent ability of looking at its flaws. I feel that this is one of the things that I have loved about this culture. That there is something public about looking at our flaws. And I think it’s the mark of a culture that’s evolving in a very positive direction.

Laine Perfas: Thinking about the coming new year, ’tis the season for New Year’s resolutions and all of these dramatic statements of changes that people are going to make. I’m curious what you all think is beautiful about change and how it can have a healthy place in our lives as we think about changes we might want to make this upcoming year?

Waldinger: Zen perspective? Change is absolutely inevitable. Change is constant. Change is the only constant. And the more we resist change, the more we suffer. There’s a phrase I like, it says, “Let go or be dragged.” That there is just constant movement of the universe and of us as individuals as part of the universe. So I would say, it’s like gravity. It’s just here, it’s with us.

Banaji: But which direction it goes in, the change it’s going to have? That, I think, is for every single one of us to continue to try to shape as best as we see it. And I think in that sense, this year is going to be even more important than other years.

Laine Perfas: Thank you all for joining me for this really wonderful conversation today.

Waldinger: Yeah. What fun.

Laine Perfas: Thanks for listening. To find a transcript of this episode and to listen to all of our other episodes, visit harvard.edu/thinking. This episode was hosted and produced by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was edited by Ryan Mulcahy, Simona Covel, and Paul Makishima, with additional editing and production support from Sarah Lamodi. Original music and sound design by Noel Flatt. Produced by Harvard University, copyright 2024.