Danger ahead

Danger ahead

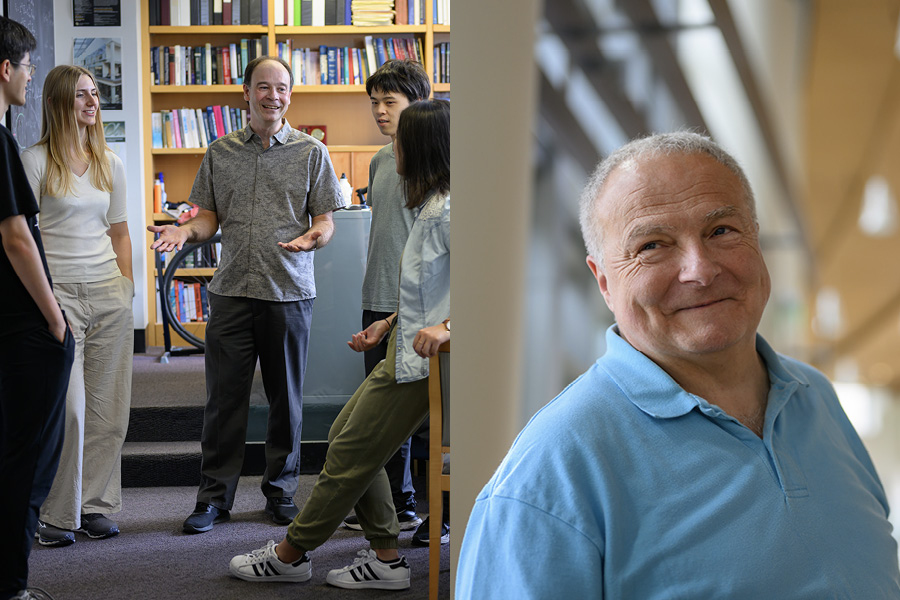

In advance of his lecture at Harvard Thursday, former national security official Ben Rhodes spoke to the Gazette about global trade, hotspots including Syria and Gaza, and the state of U.S. relations with China, Russia, and other nations.

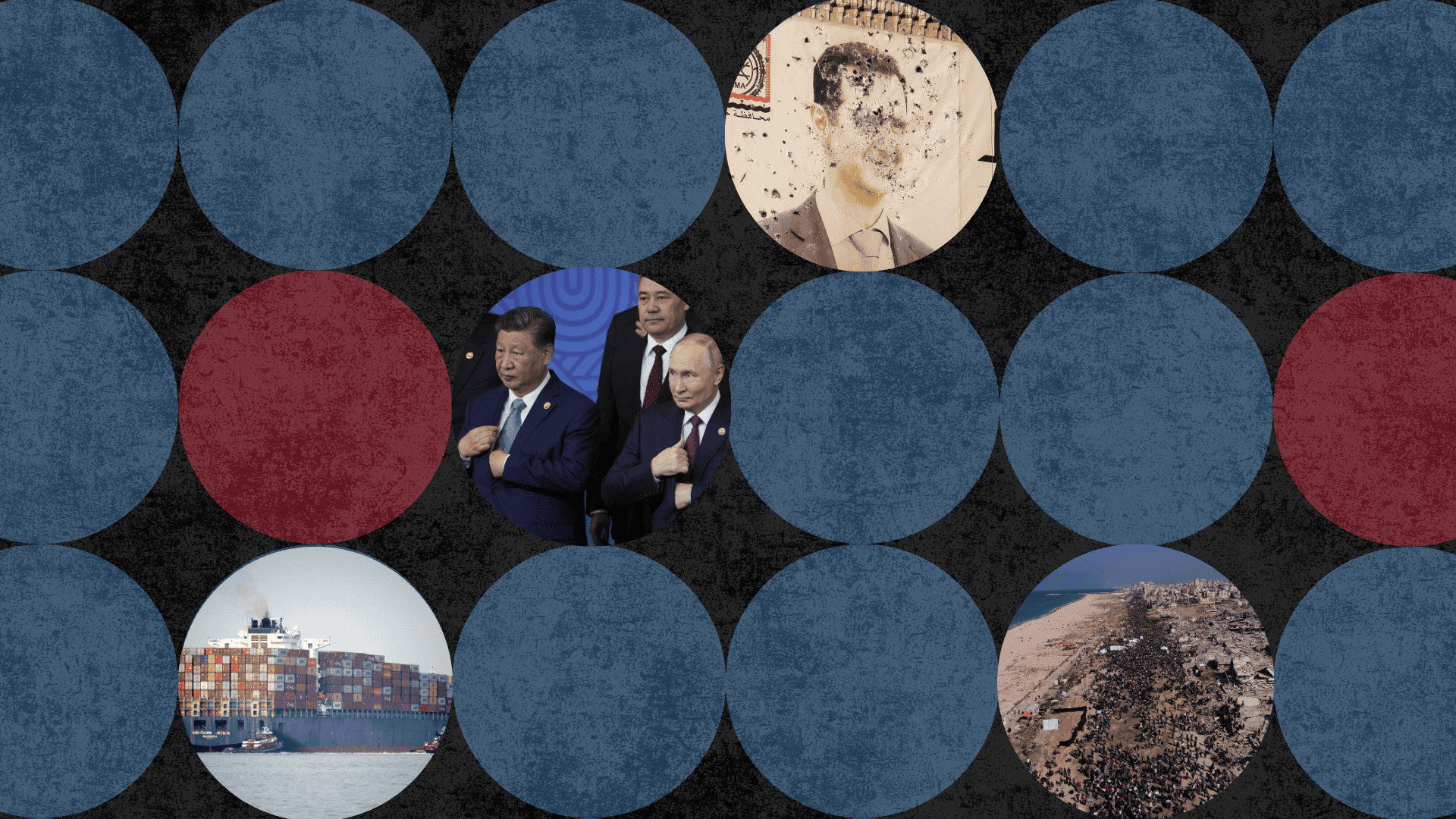

AP photos by Deccio Serrano (from left), Maxim Shipenkov, Omar Albam, and Mohammad Abu Samra; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Christina Pazzanese

Harvard Staff Writer

Former national security official surveys hot spots in Middle East, Asia, Eastern Europe — and how new president’s ideas are being received

Last year was a tumultuous one: conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine, Lebanon, and Sudan; the ouster of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad; increasing tension between Israel and Iran, and China and the U.S. and Taiwan; and a record 4 billion voters who ousted incumbent leaders in numerous countries. What’s in store for 2025?

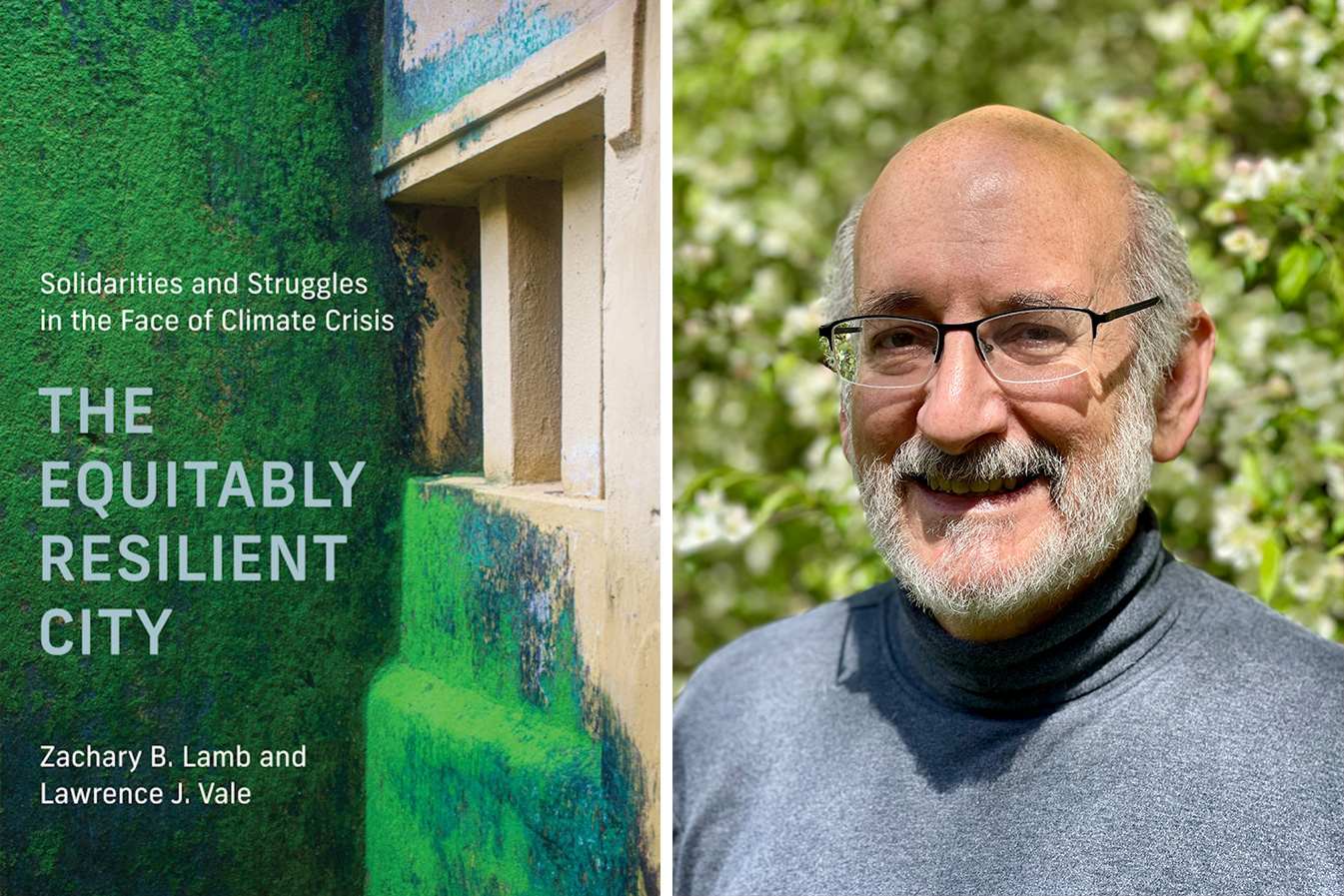

In this edited Jan. 27 conversation, Ben Rhodes, former deputy national security adviser and speechwriter to President Barack Obama, discusses what may lie ahead in key global hotspots and how other countries are reacting to some new foreign policy ideas floated by President Donald Trump. Rhodes, who spoke to the Gazette before Trump’s Feb. 4 meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyanhu, will deliver the Warren and Anita Manshel Lecture in American Foreign Policy on Thursday.

Given the current state of upheaval around the globe, what would you flag as top concerns if you were advising the president on national security today?

I guess there are two things I would point to: We’re in this period where there is no longer the international order that governed geopolitics for the last several decades, and there is a normalization of conflict happening.

When you look at Ukraine, at the Middle East, and Taiwan, the possibility of great power conflict feels uncomfortably high right now. You have a return to a pre-World War I absence of rules, large countries ignoring norms and getting comfortable with territorial conquest without mechanisms to resolve conflicts because the system isn’t working anymore. And so, the first thing is to take seriously the risk of escalating global conflict.

The second thing are structural issues: climate, artificial intelligence, and nuclear weapons once again. We seem to be headed in a direction of a new nuclear arms race, an absence of rules around the proliferation of artificial intelligence, which is going to create all kinds of risks, and an absence of coordinated effort on climate. Those things are connected. In the absence of diplomacy and great working power relations, both the ability to stop conflict and avoid it and to address the defining issues is currently absent. And that, to me, is the biggest risk.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres recently said the Middle East “is in a period of profound transition, rife with uncertainty but also possibility.” What may be on the horizon?

There’s some promising developments. The removal of Assad, obviously, is a very positive development that creates an opening for Syria and Lebanon to have a better future. You have the Gulf states, not just in their relations, but in their autocratic prosperity model, trying to bring about a paradigm of stability and interconnection with the rest of the world.

But I just think you have massive challenges remaining. In addition to the Palestinians, one of the underappreciated risks right now is how brittle the governments are in Egypt and Jordan in a way that I feel some echoes of the pre-Arab Spring times. In Egypt, you have a very unpopular and corrupt military government and a very dissatisfied, if not angry, population. And in Jordan, you have a perennially somewhat-vulnerable monarchy with a large Palestinian population. And so, there’s the potential for surprises in the Middle East beyond what is already happening.

And then, of course, you have the unresolved question of Iran. Yes, Iran is weakened, but to what end when you consider the nuclear program? Does that lead you in the direction of trying to make a diplomatic agreement along the lines of what we did in the 2015 nuclear deal, or does that lead to the potential for a military conflict involving the United States and Iran?

The new administration has to determine whether they are going to pursue a regime-change type approach toward Iran or a military option related to the nuclear program, given how far advanced it is, or are they going to try to resolve that issue diplomatically, thinking they have a stronger hand to play? As clear as Trump has been on a lot of things the last few days, that remains kind of an open question.

“You have a return to a pre-World War I absence of rules, large countries ignoring norms and getting comfortable with territorial conquest.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Trump have signaled they may have an interest in a broader discussion that would include Ukraine but also nuclear arms control and lifting sanctions, according to The New York Times. If accurate, what might that all mean?

Putin would definitely want to enlarge the agenda because he sees Ukraine as connected to this larger conflict with the United States, from the future of NATO to nuclear arms control to the sanctions on the Russian economy. So, Putin has a lot of interest in enlarging that agenda.

It wouldn’t surprise me if Trump is inclined to do that because Trump is less viscerally focused on Ukrainian sovereignty and the right and wrong of the conflict. I don’t even mean that as a criticism: If you take Trump’s transactional worldview, Ukraine is more like a piece of a larger puzzle.

The Biden team did not accept this premise of seeing Ukraine in a bigger context, because to them, it was about the right and wrong of what Russia was doing in Ukraine. But ultimately, that’s the reality, and if it’s easier to make progress in a negotiation that might include some benefit to Ukraine by enlarging the agenda, it’s worth testing. I’m always in favor of diplomacy, or at least exploring it. But we have to be realistic that that may not work unless Trump is willing to trade away things past presidents weren’t willing to trade away in the U.S.-Russia relationship.

U.S.-China relations ran hot and cold during Trump’s first term. Now, with Trump’s willingness to resolve the TikTok ban but also increasing tariffs, the White House is sending more mixed signals. What direction is this relationship headed?

As with the Iran question, this is one where it’s not clear to me exactly where Trump is going to go. He has filled his national security team with people who see us not just in an economic conflict with China, but in a geopolitical and ideological conflict with China.

I took the TikTok ban as an early indication that Trump’s more pragmatic approach is more likely to prevail. TikTok is the ultimate example of an issue that is about ideology and influence, and, to some extent, geopolitics. Trump wasn’t willing to go to the mat on that despite having a piece of legislation that had been passed under the previous administration.

To me, it suggests that he’ll be more focused on the trade piece. I’d expect tariffs; I’d expect a trade war of sorts; but I’m not sure that it’s going to be the Republican Hawk version of a China policy that would have a huge Taiwan focus and be more focused on these ideological questions.

Some of the things Trump is doing are going to help China. Trump’s pivot back to fossil fuels is perfectly aligned with China’s focus on dominating clean energy technologies and supply chains. On AI, as we’ve been seeing, China’s figuring out how to work around all these sanctions and export controls.

If I’m China, what I’m doing in the Trump years is taking advantage of all the things Trump is going to break in Europe, in Africa, and Latin America. There’s more opportunity for China in a Trump presidency than people might see on the surface.

How are allies and adversaries interpreting talk about the U.S. annexing Greenland, the Panama Canal, or Canada?

I think people take the Greenland threat very seriously. I don’t like the idea of returning to territorial expansionism, but there is a credible interest the U.S. has. Greenland is a massive territory; it has enormous natural resources that are going to be more accessible with climate change, and it’s strategically located vis-a-vis Russia and China, to some extent.

Denmark’s hold on that is quite tenuous. So, of the three, Greenland feels like it could become a real source of tension.

The Arctic is incredibly important. It would definitely serve the strategic interest in the United States if Greenland were a part of the United States or a territory of the United States. My concern is that while there’s a lot of strategic interest, the global risk of it being part of a slide toward a larger conflict is real.