Study: Burning heavy fuel oil with scrubbers is the best available option for bulk maritime shipping

When the International Maritime Organization enacted a mandatory cap on the sulfur content of marine fuels in 2020, with an eye toward reducing harmful environmental and health impacts, it left shipping companies with three main options.

They could burn low-sulfur fossil fuels, like marine gas oil, or install cleaning systems to remove sulfur from the exhaust gas produced by burning heavy fuel oil. Biofuels with lower sulfur content offer another alternative, though their limited availability makes them a less feasible option.

While installing exhaust gas cleaning systems, known as scrubbers, is the most feasible and cost-effective option, there has been a great deal of uncertainty among firms, policymakers, and scientists as to how “green” these scrubbers are.

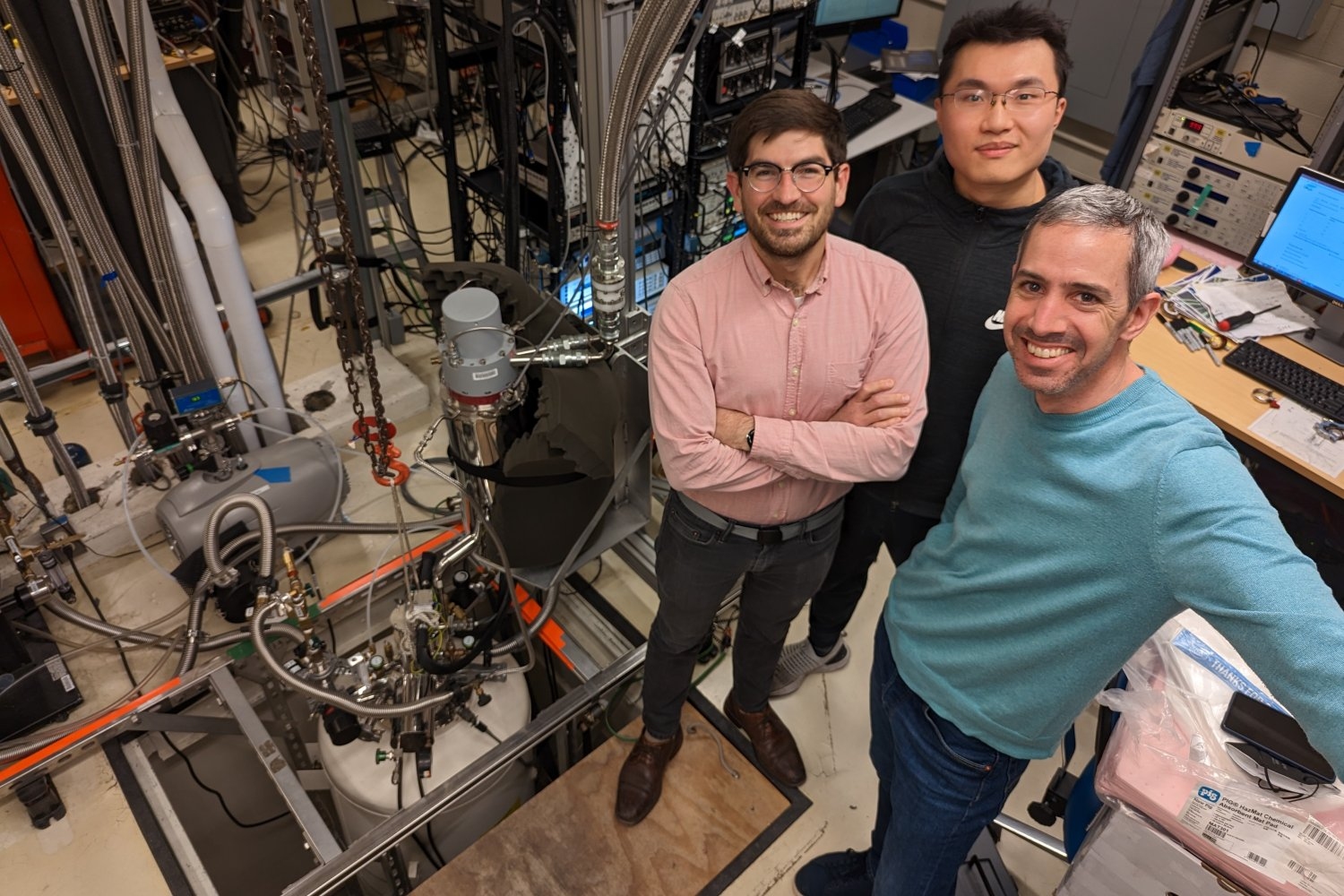

Through a novel lifecycle assessment, researchers from MIT, Georgia Tech, and elsewhere have now found that burning heavy fuel oil with scrubbers in the open ocean can match or surpass using low-sulfur fuels, when a wide variety of environmental factors is considered.

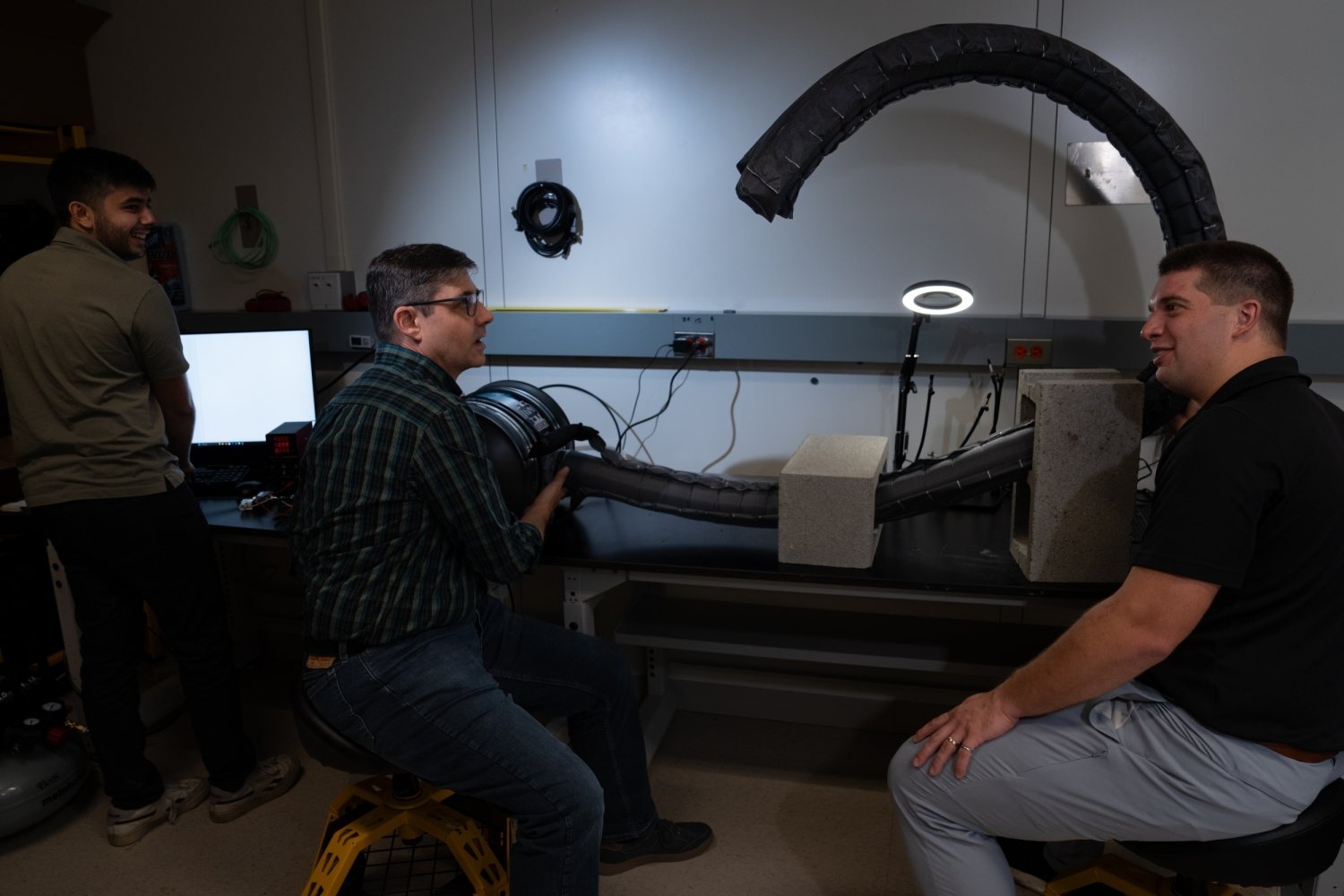

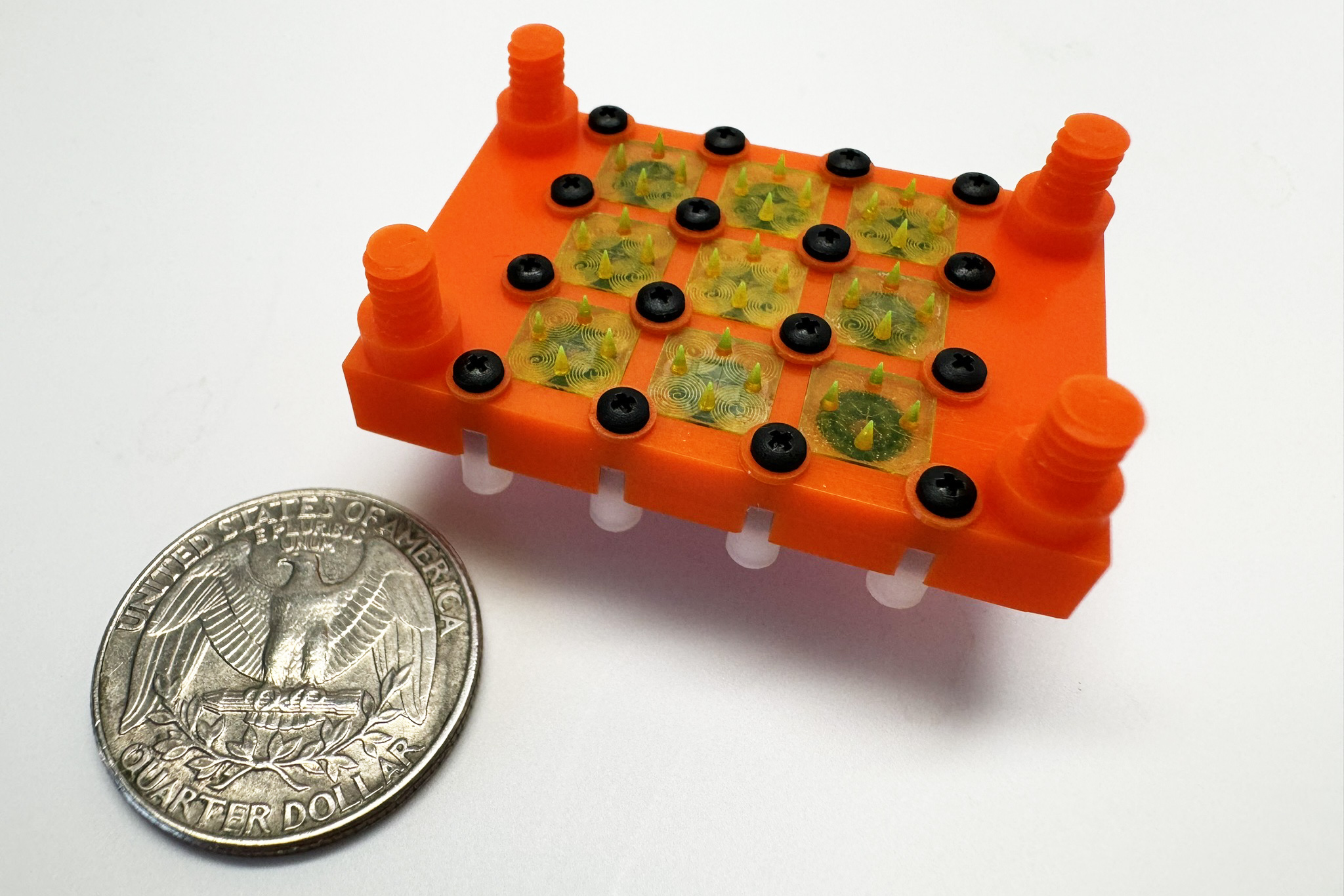

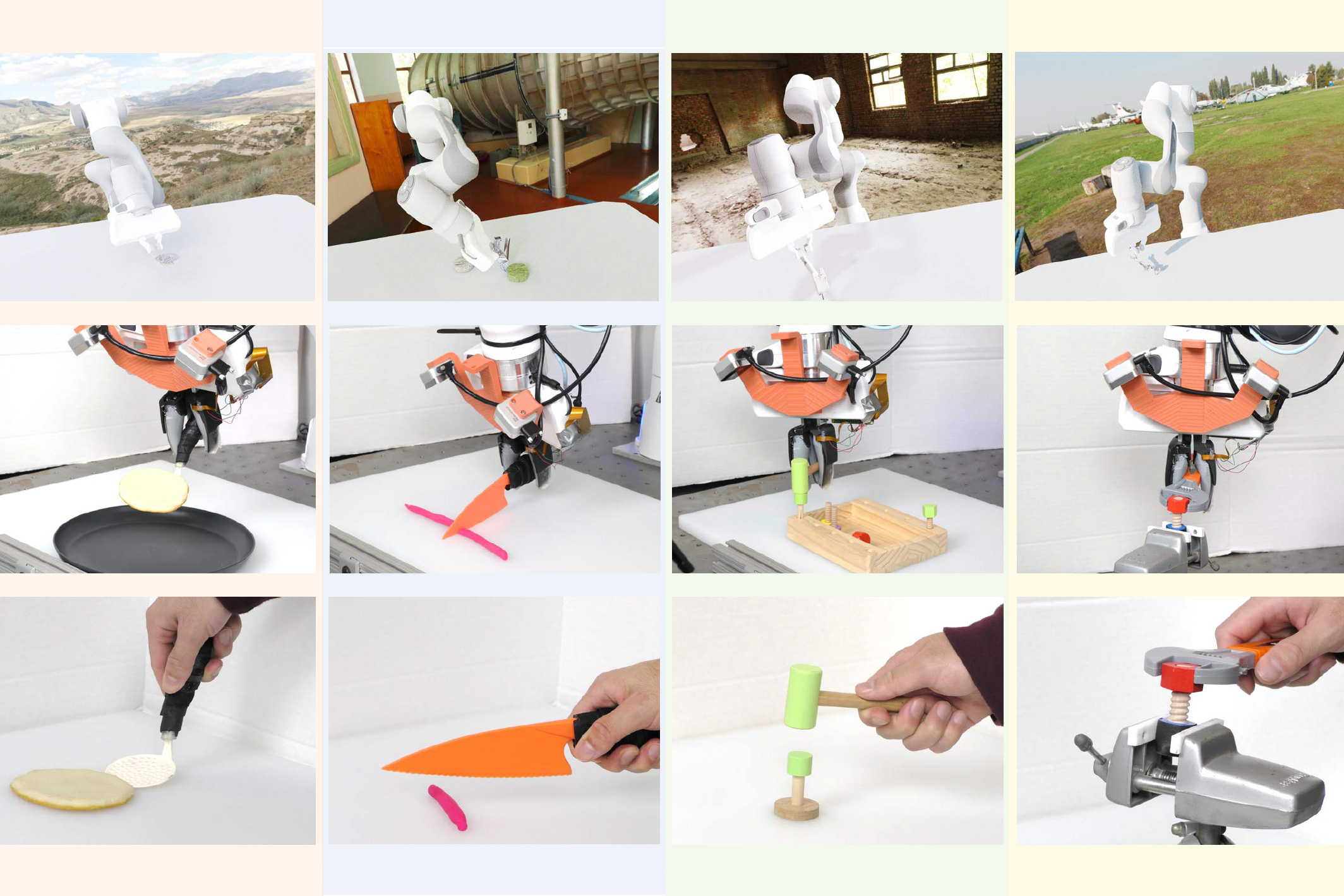

The scientists combined data on the production and operation of scrubbers and fuels with emissions measurements taken onboard an oceangoing cargo ship.

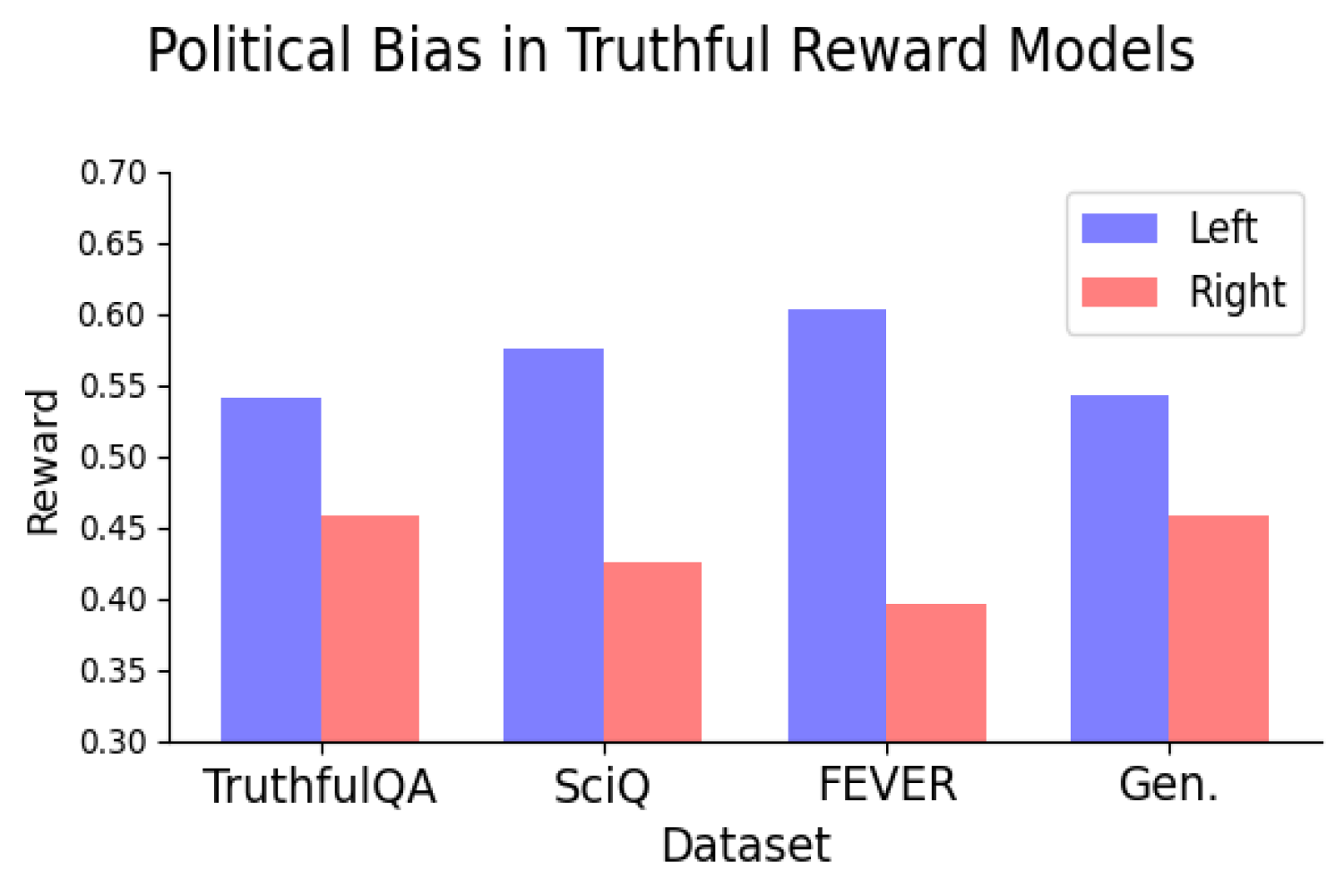

They found that, when the entire supply chain is considered, burning heavy fuel oil with scrubbers was the least harmful option in terms of nearly all 10 environmental impact factors they studied, such as greenhouse gas emissions, terrestrial acidification, and ozone formation.

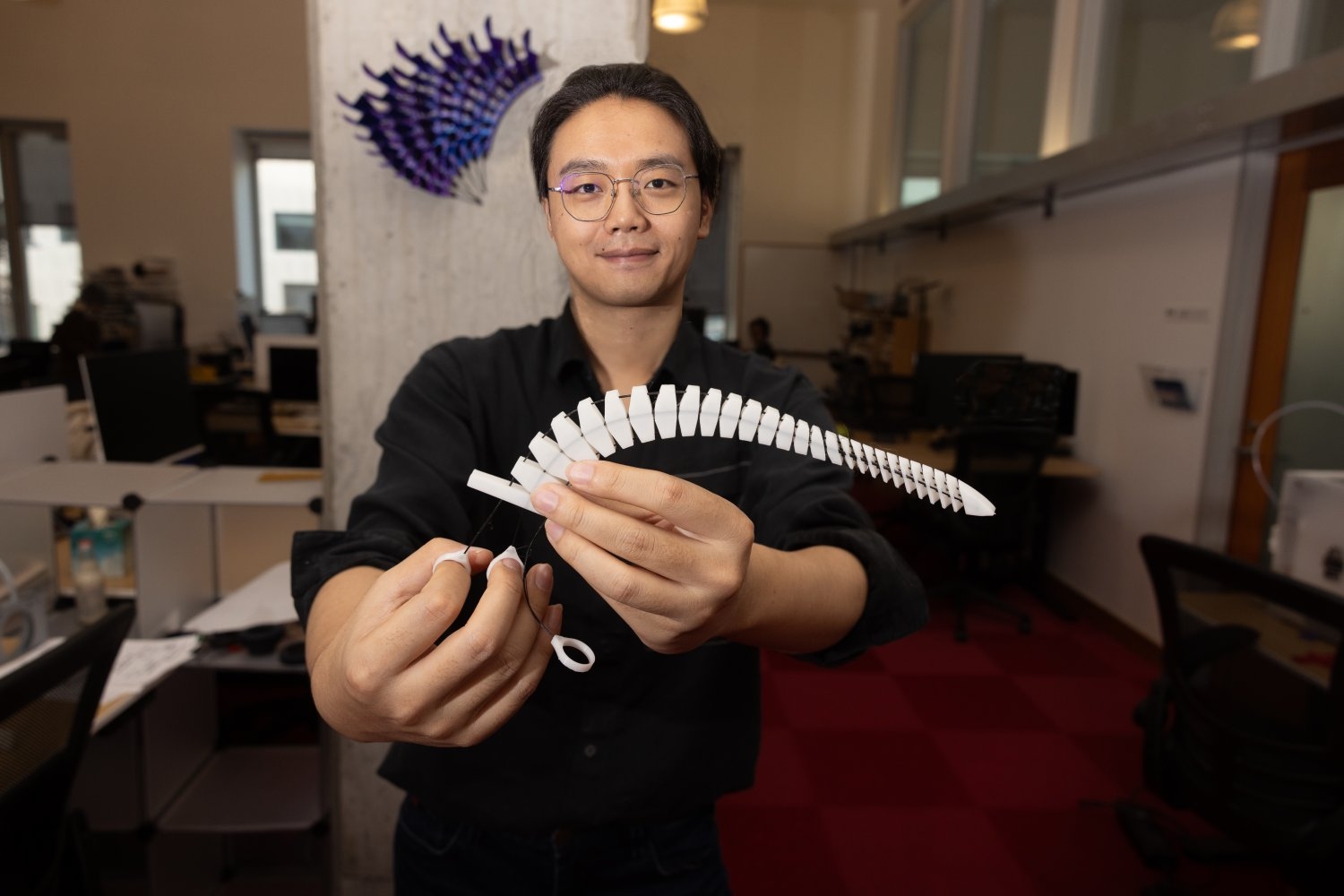

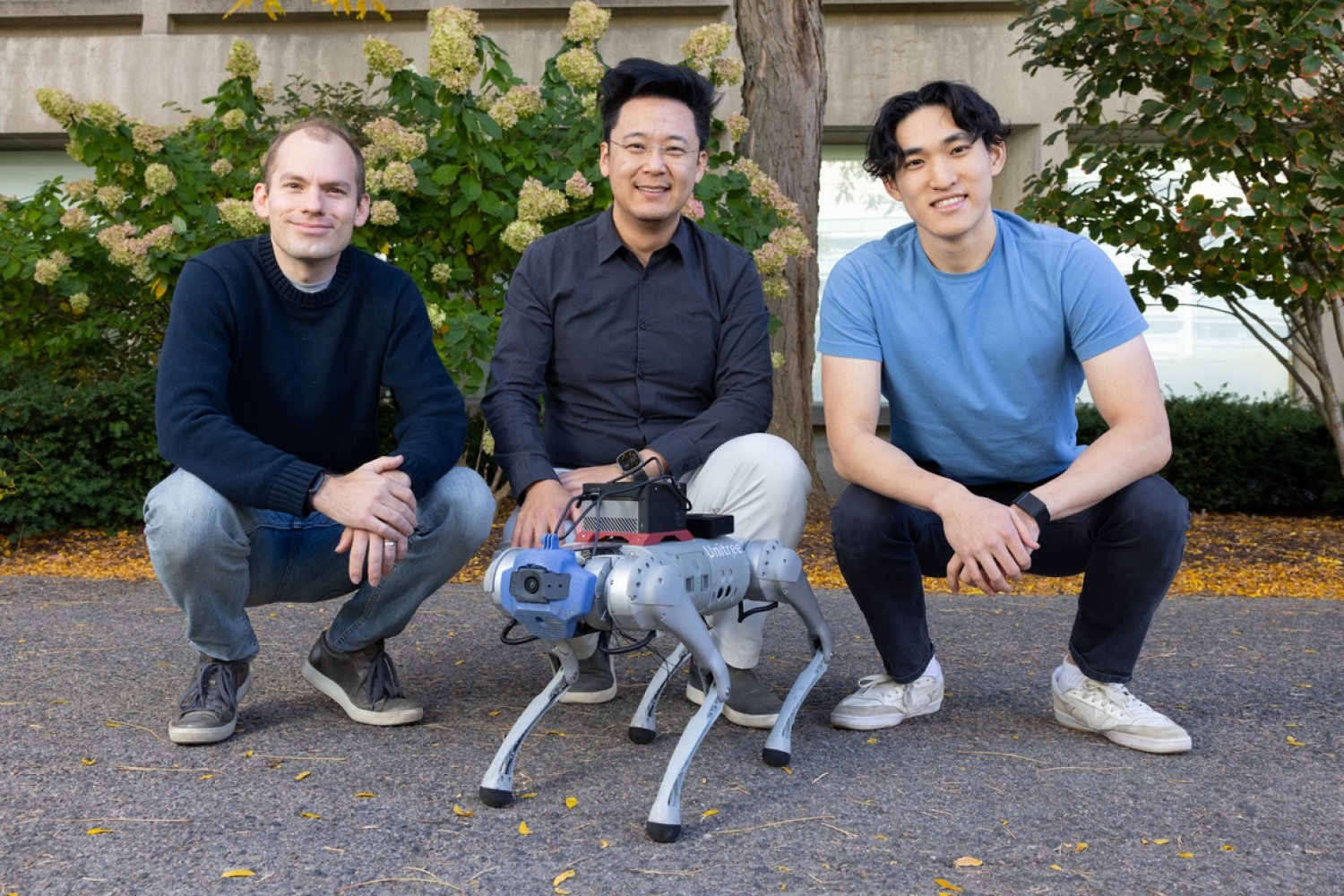

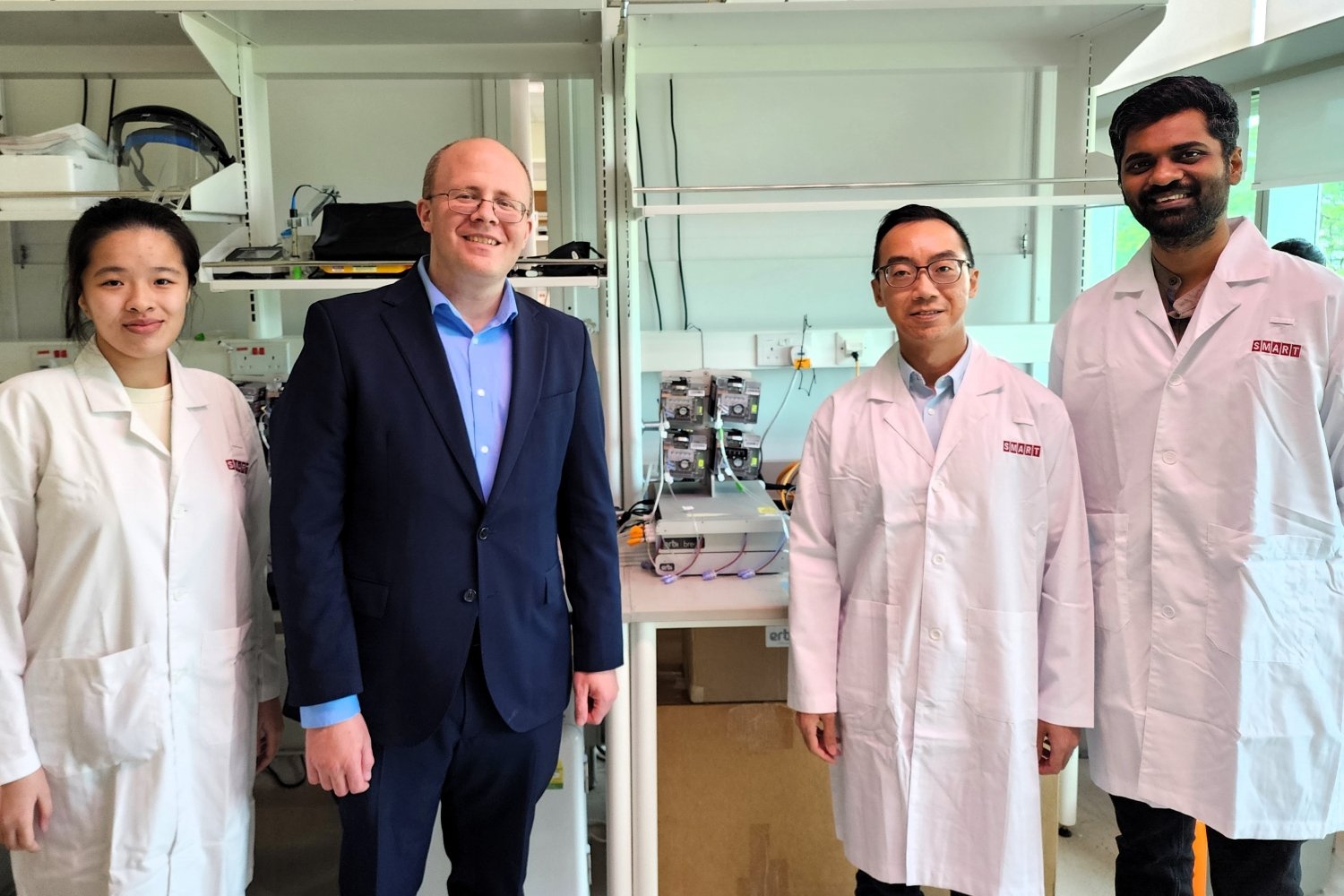

“In our collaboration with Oldendorff Carriers to broadly explore reducing the environmental impact of shipping, this study of scrubbers turned out to be an unexpectedly deep and important transitional issue,” says Neil Gershenfeld, an MIT professor, director of the Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA), and senior author of the study.

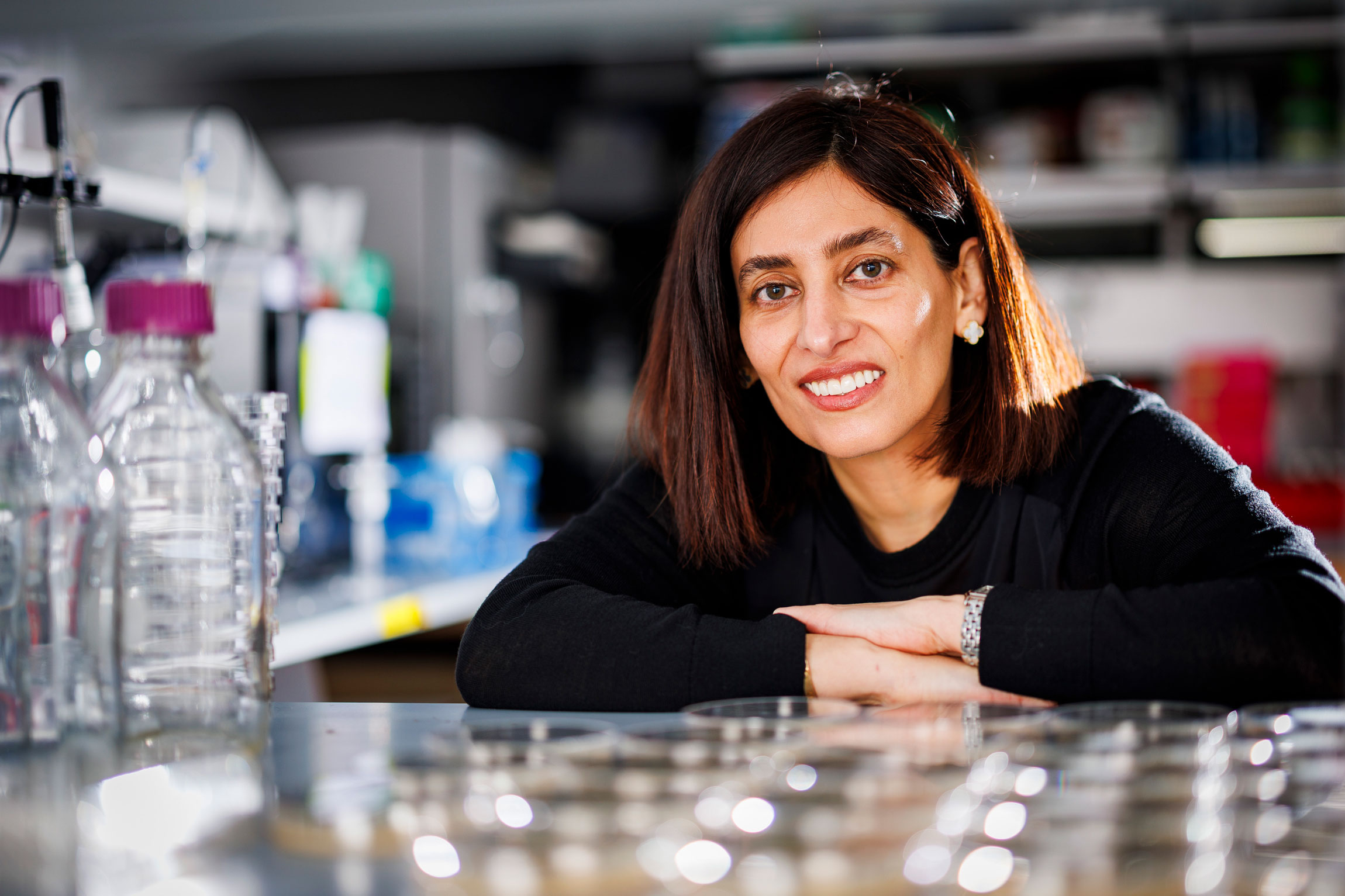

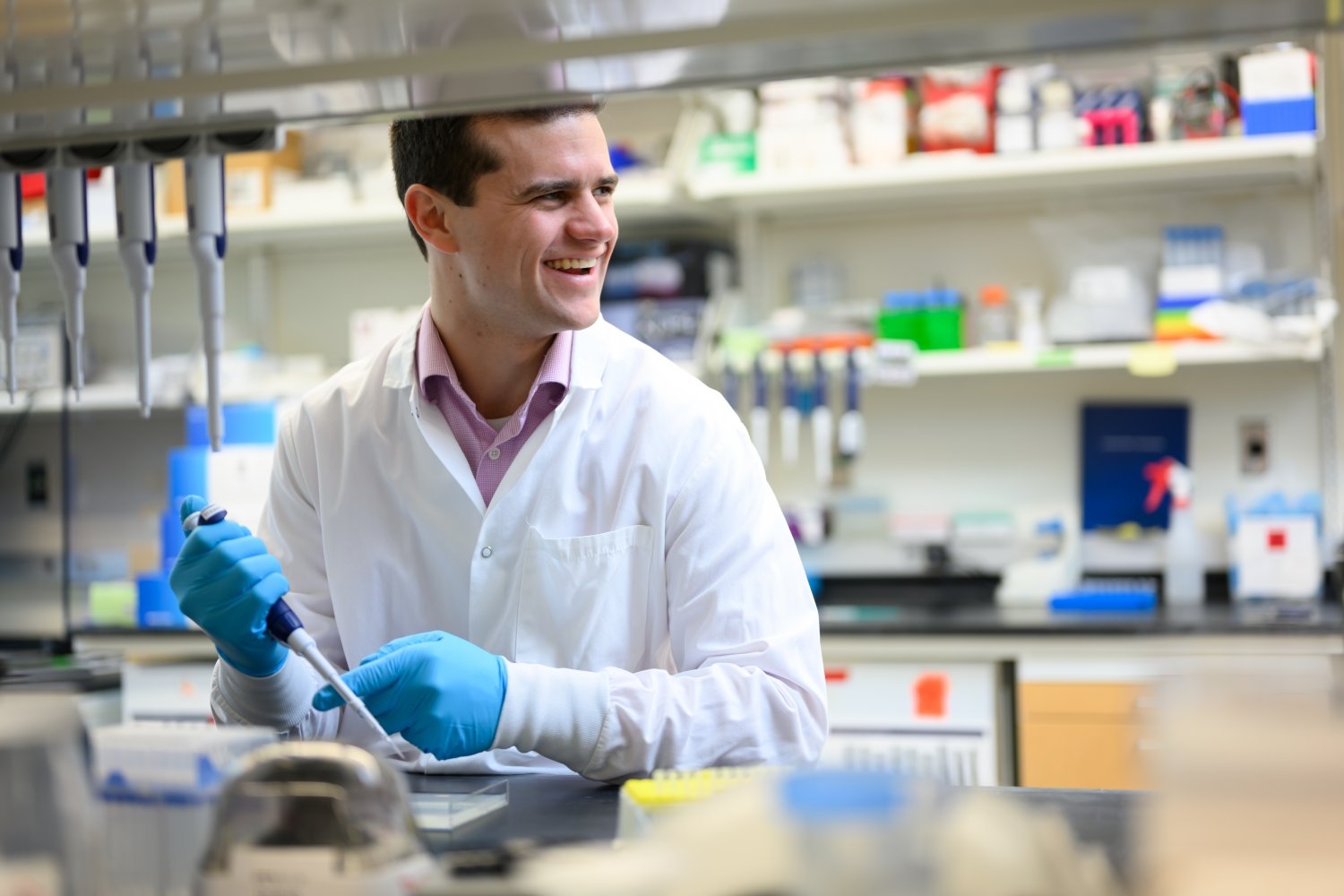

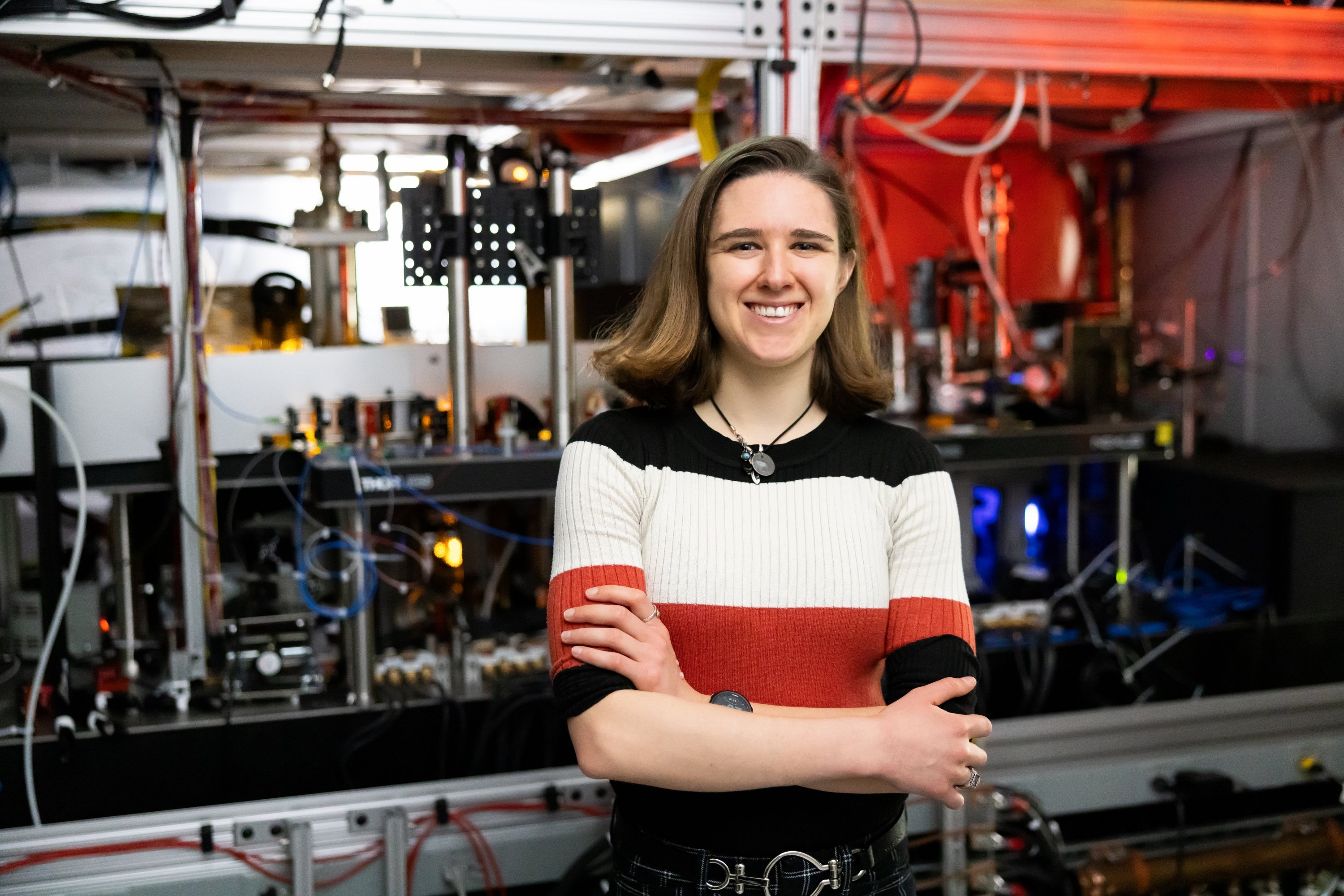

“Claims about environmental hazards and policies to mitigate them should be backed by science. You need to see the data, be objective, and design studies that take into account the full picture to be able to compare different options from an apples-to-apples perspective,” adds lead author Patricia Stathatou, an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, who began this study as a postdoc in the CBA.

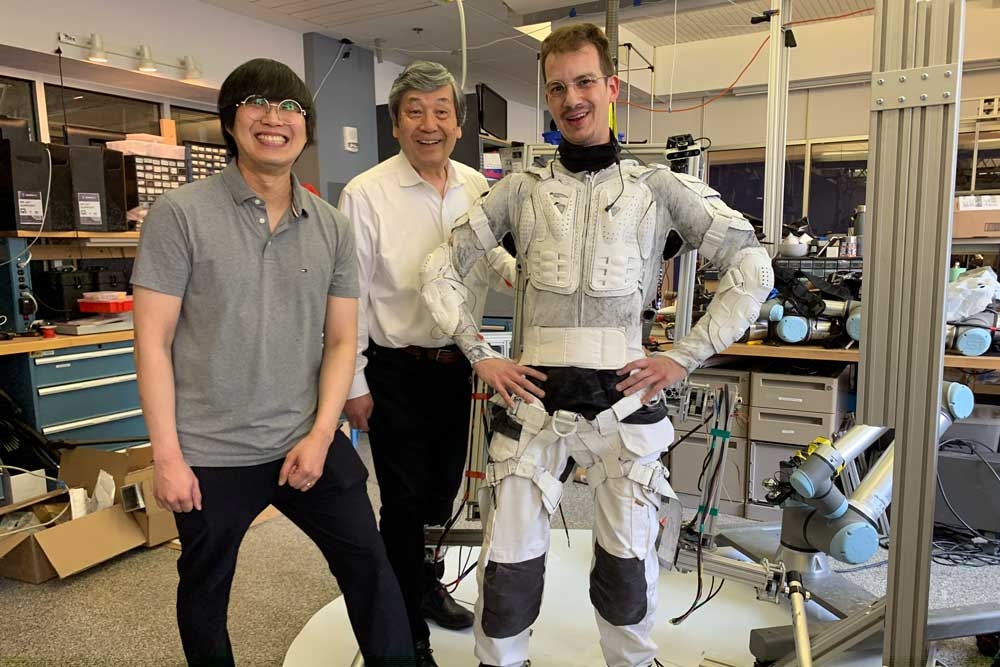

Stathatou is joined on the paper by Michael Triantafyllou, the Henry L. and Grace Doherty and others at the National Technical University of Athens in Greece and the maritime shipping firm Oldendorff Carriers. The research appears today in Environmental Science and Technology.

Slashing sulfur emissions

Heavy fuel oil, traditionally burned by bulk carriers that make up about 30 percent of the global maritime fleet, usually has a sulfur content around 2 to 3 percent. This is far higher than the International Maritime Organization’s 2020 cap of 0.5 percent in most areas of the ocean and 0.1 percent in areas near population centers or environmentally sensitive regions.

Sulfur oxide emissions contribute to air pollution and acid rain, and can damage the human respiratory system.

In 2018, fewer than 1,000 vessels employed scrubbers. After the cap went into place, higher prices of low-sulfur fossil fuels and limited availability of alternative fuels led many firms to install scrubbers so they could keep burning heavy fuel oil.

Today, more than 5,800 vessels utilize scrubbers, the majority of which are wet, open-loop scrubbers.

“Scrubbers are a very mature technology. They have traditionally been used for decades in land-based applications like power plants to remove pollutants,” Stathatou says.

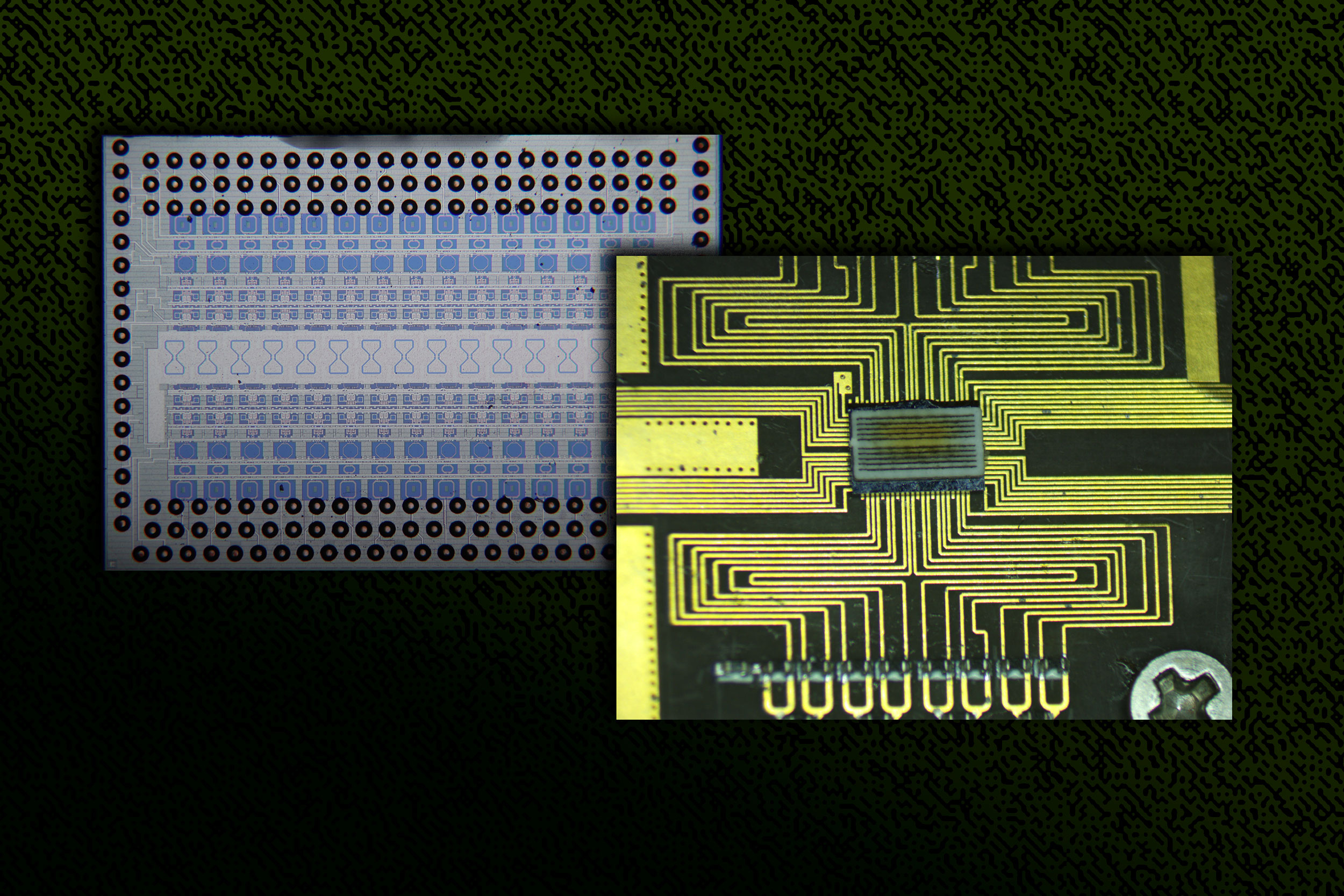

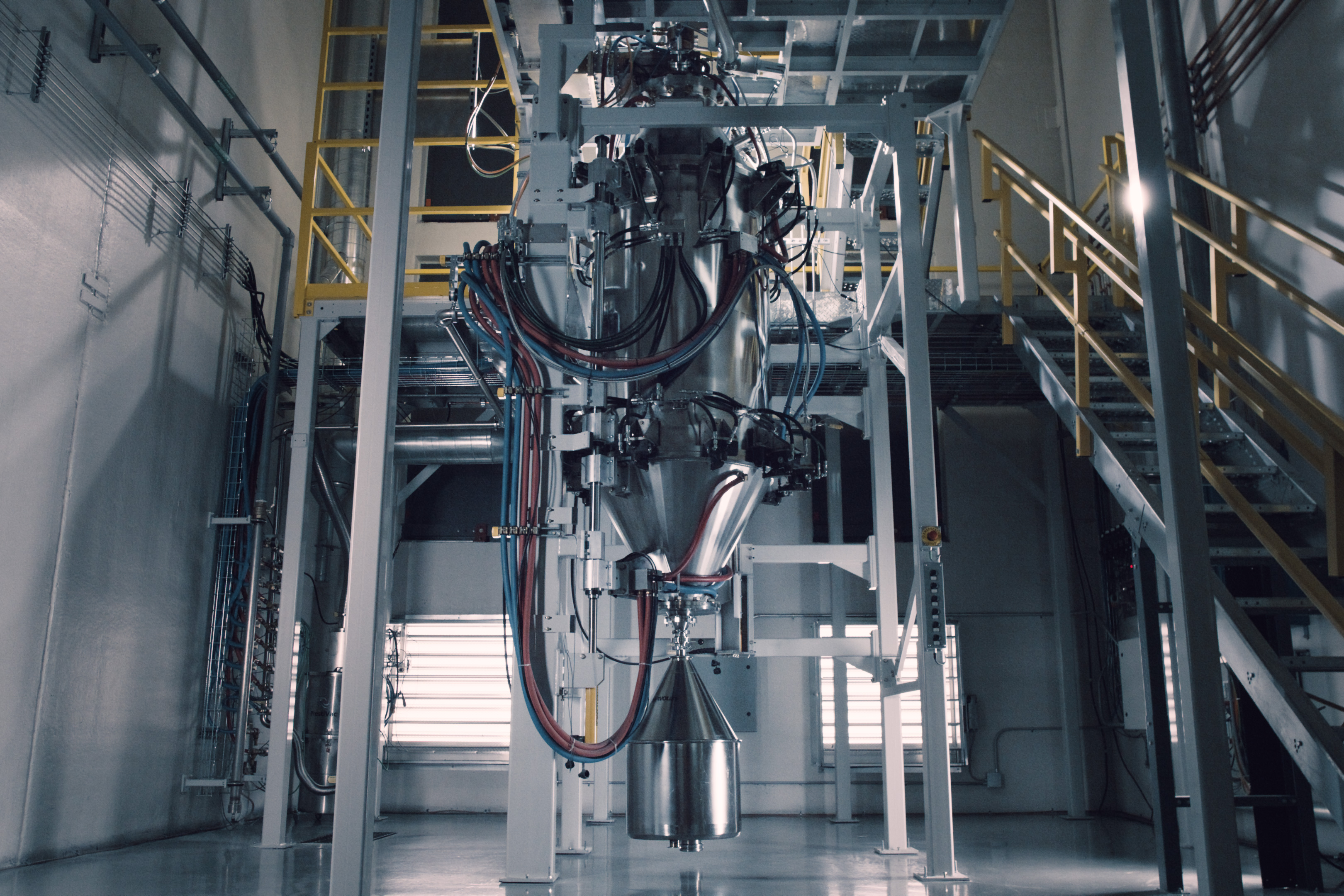

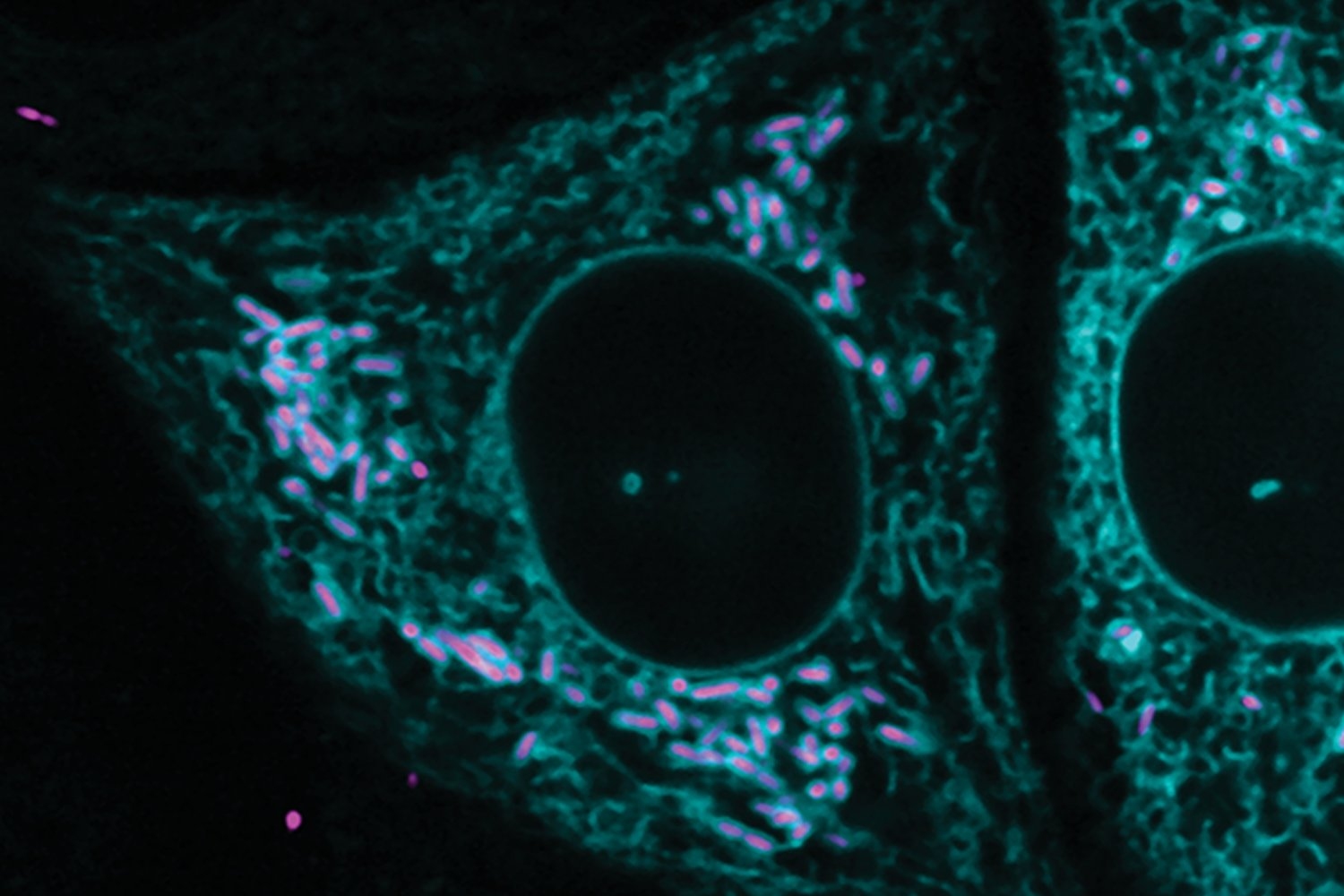

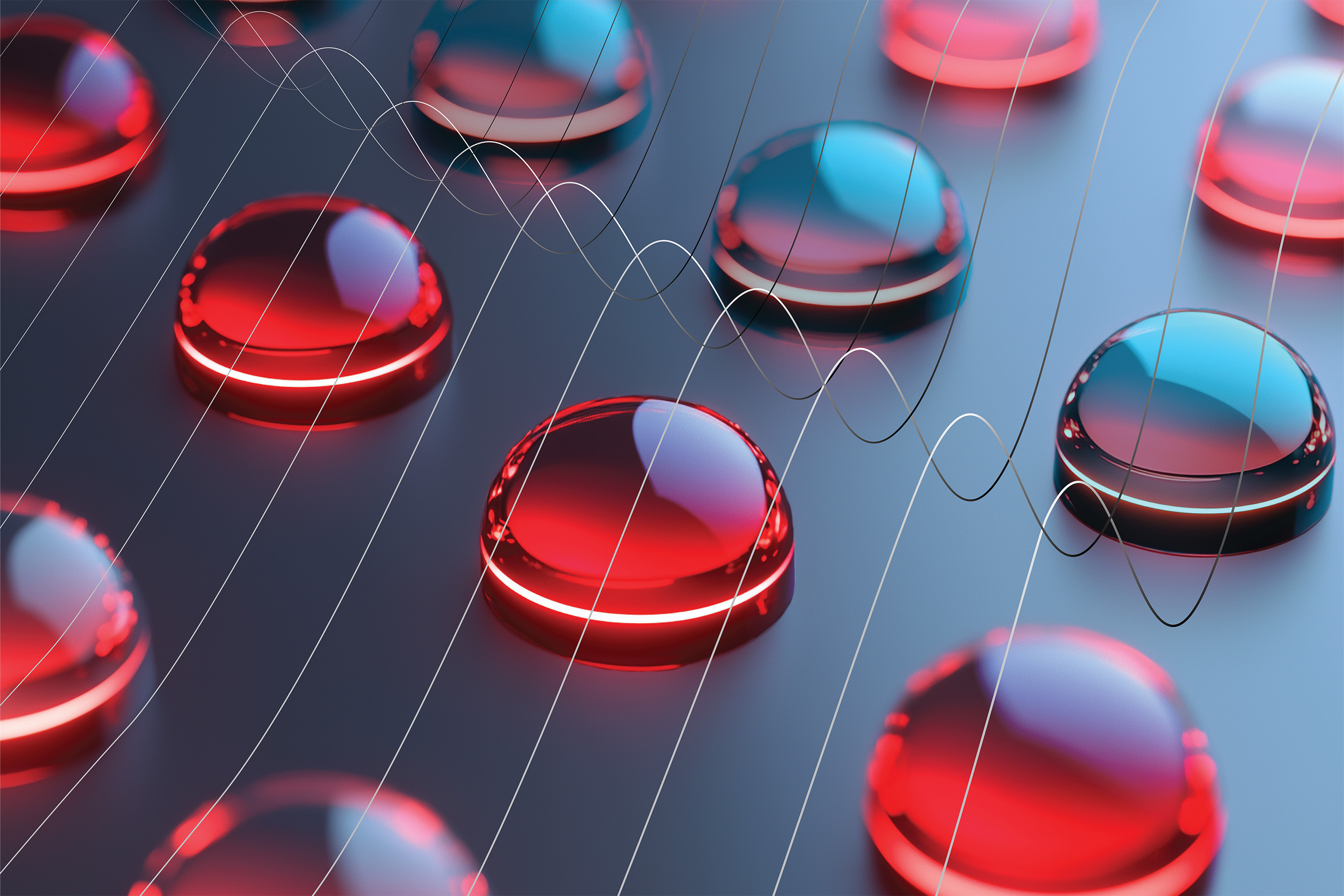

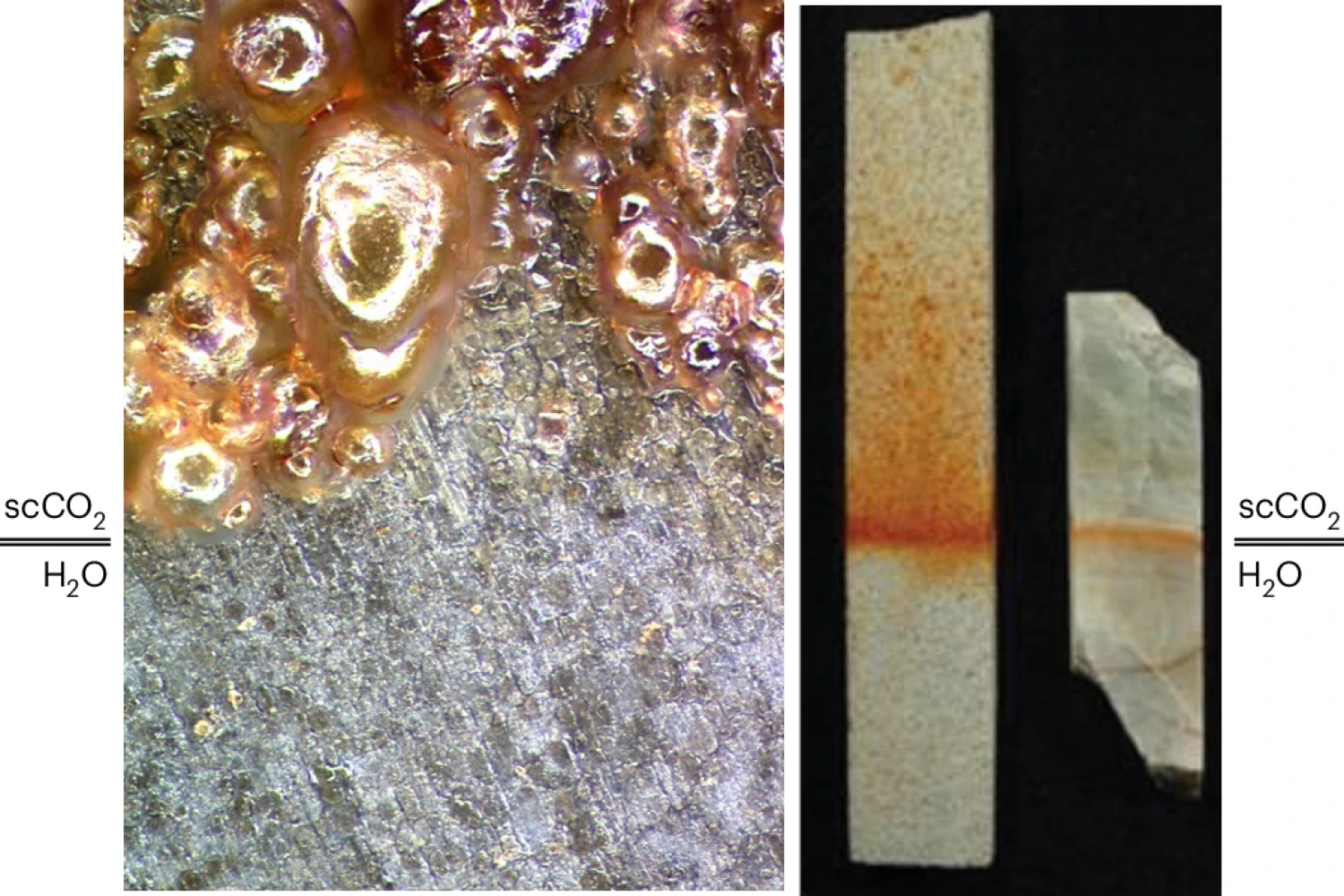

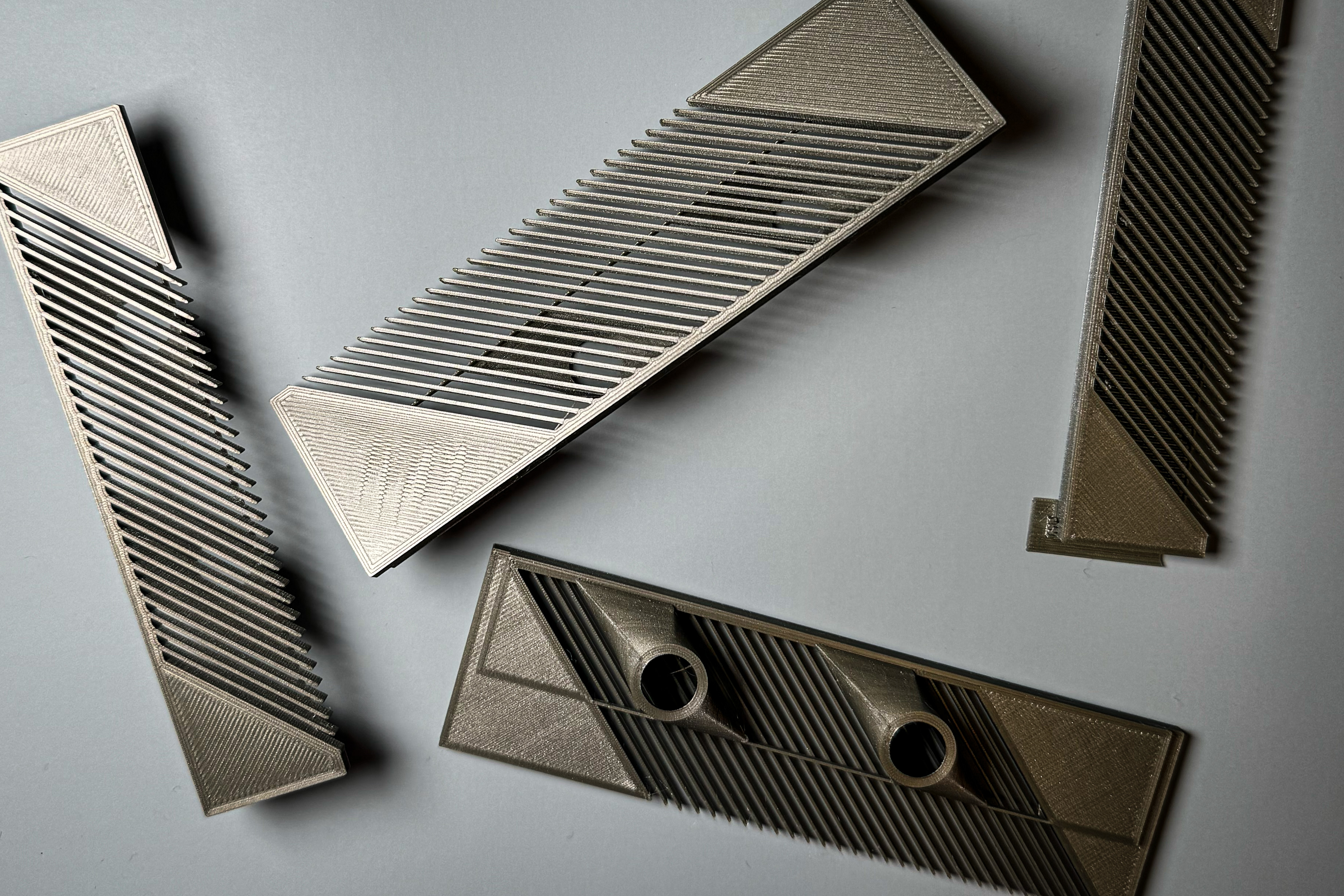

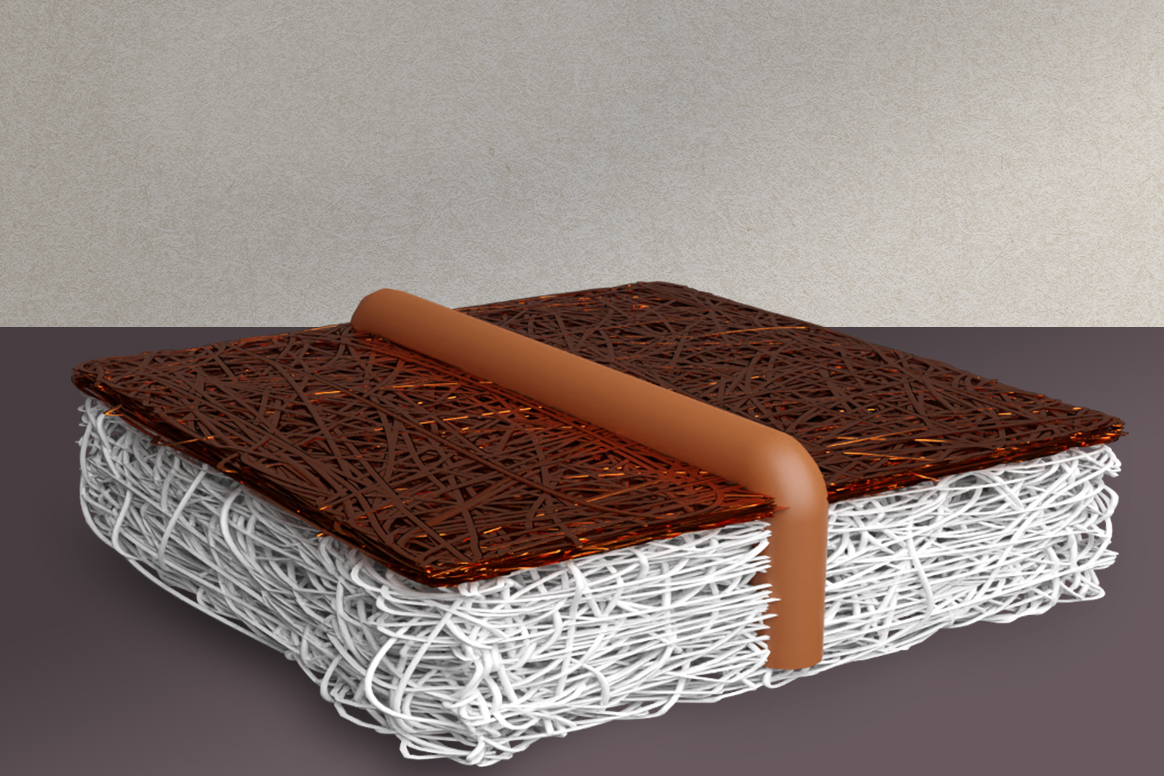

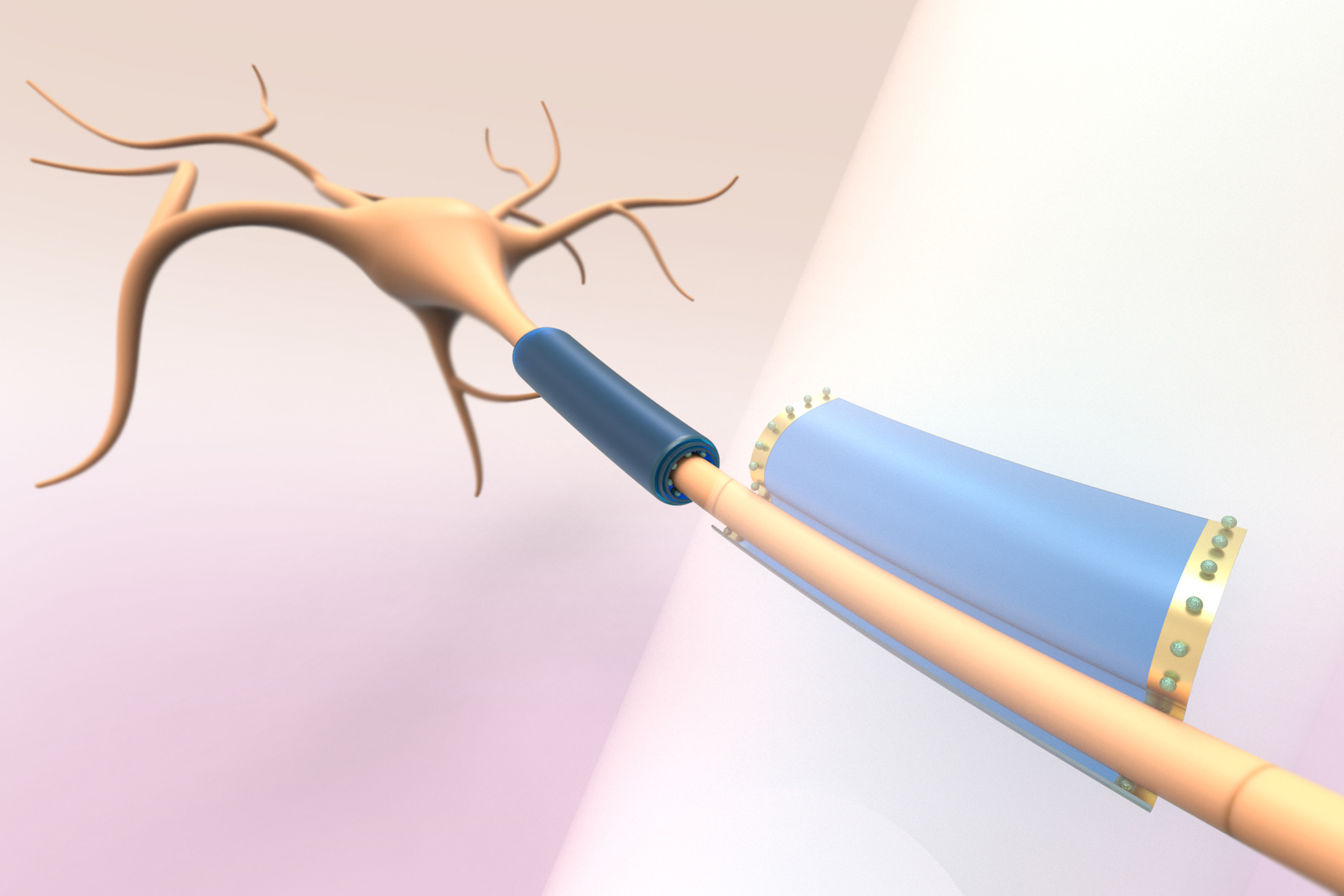

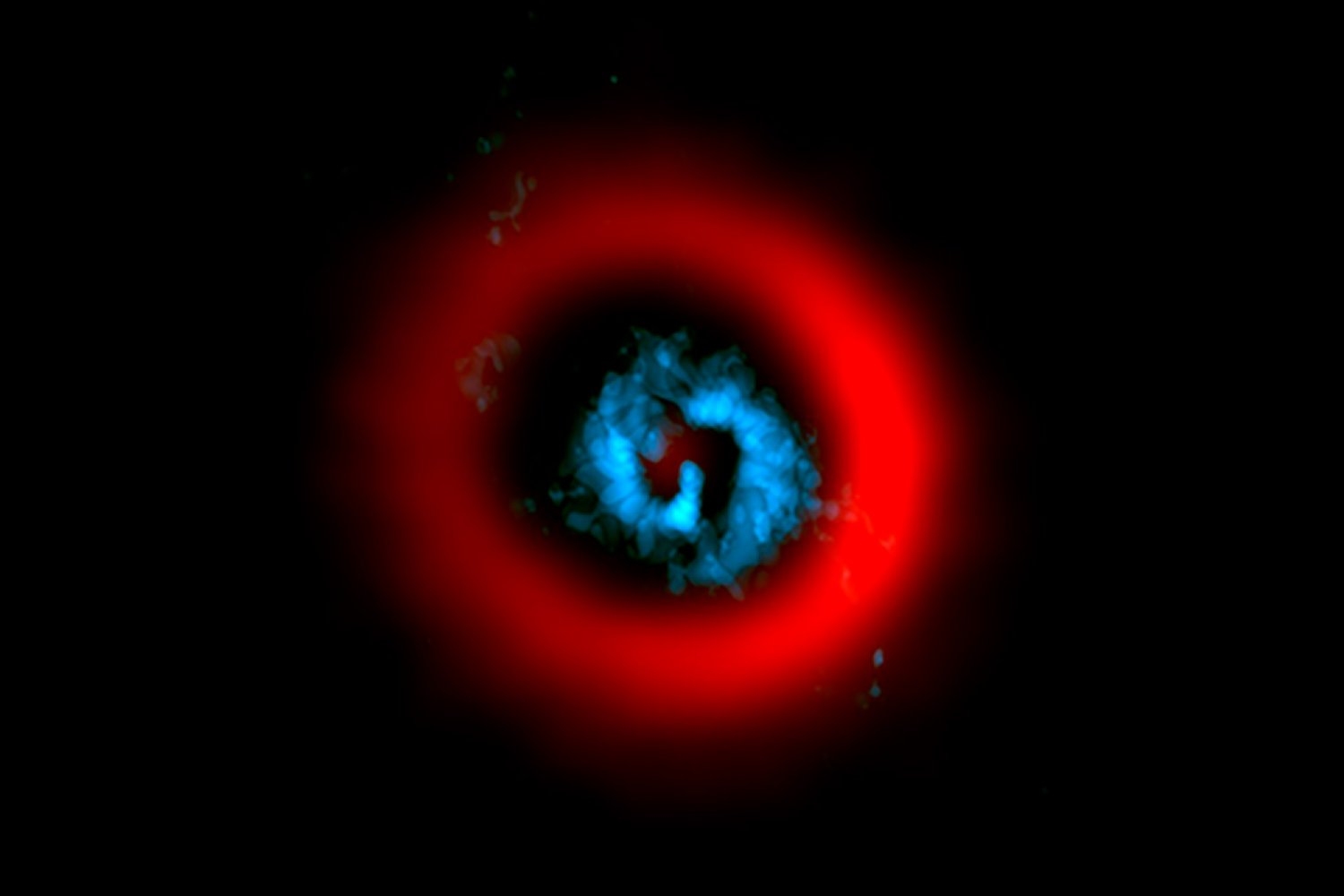

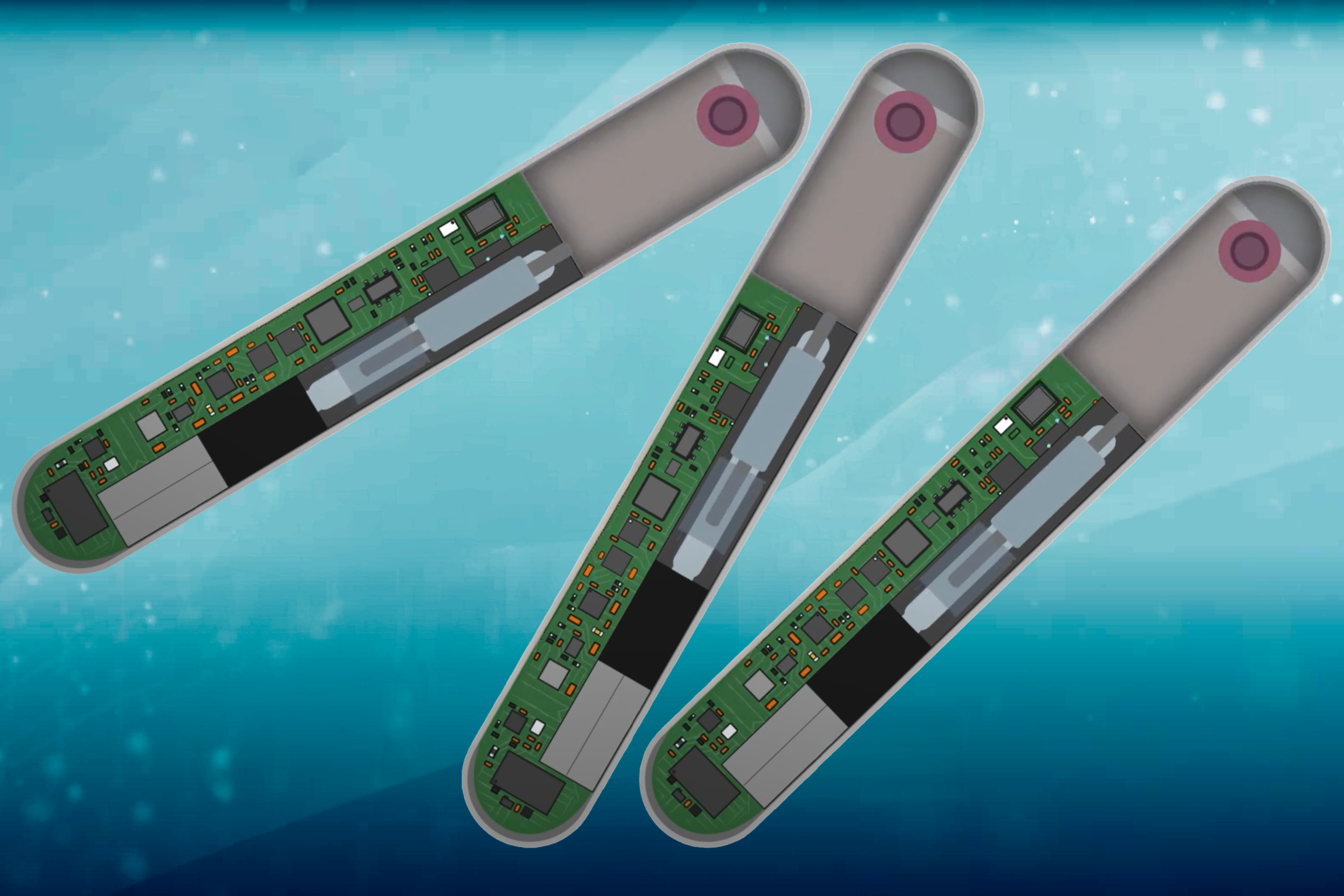

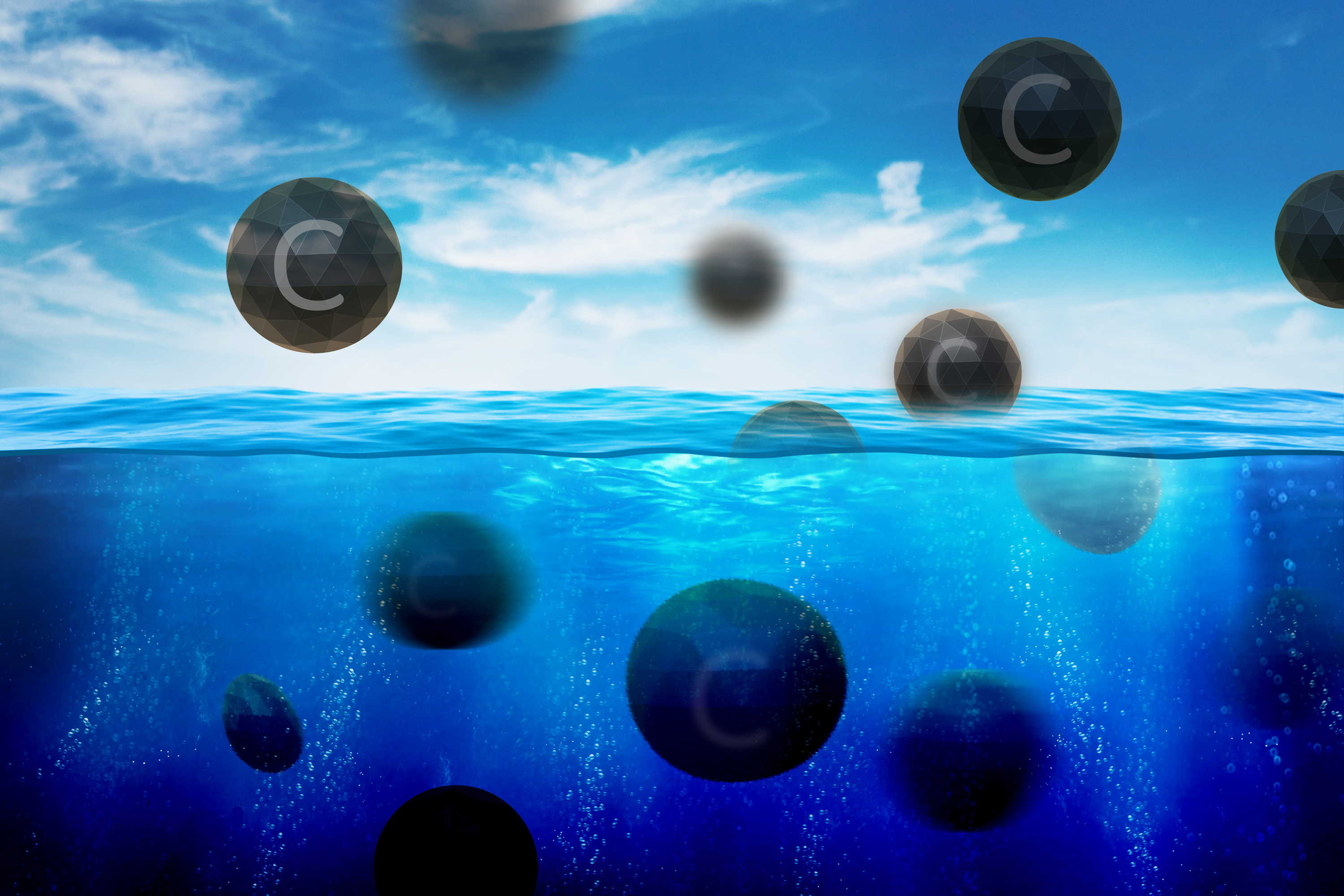

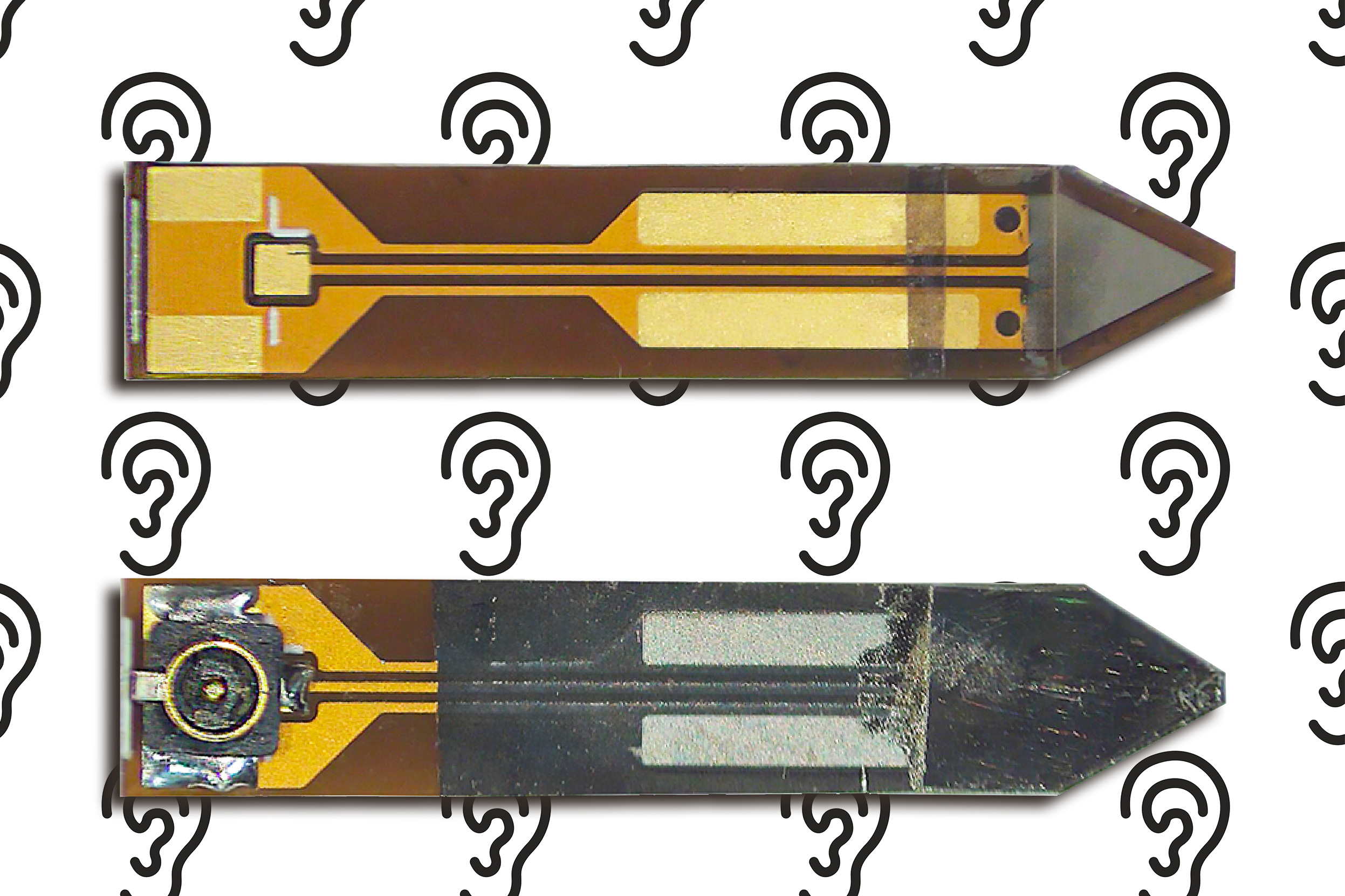

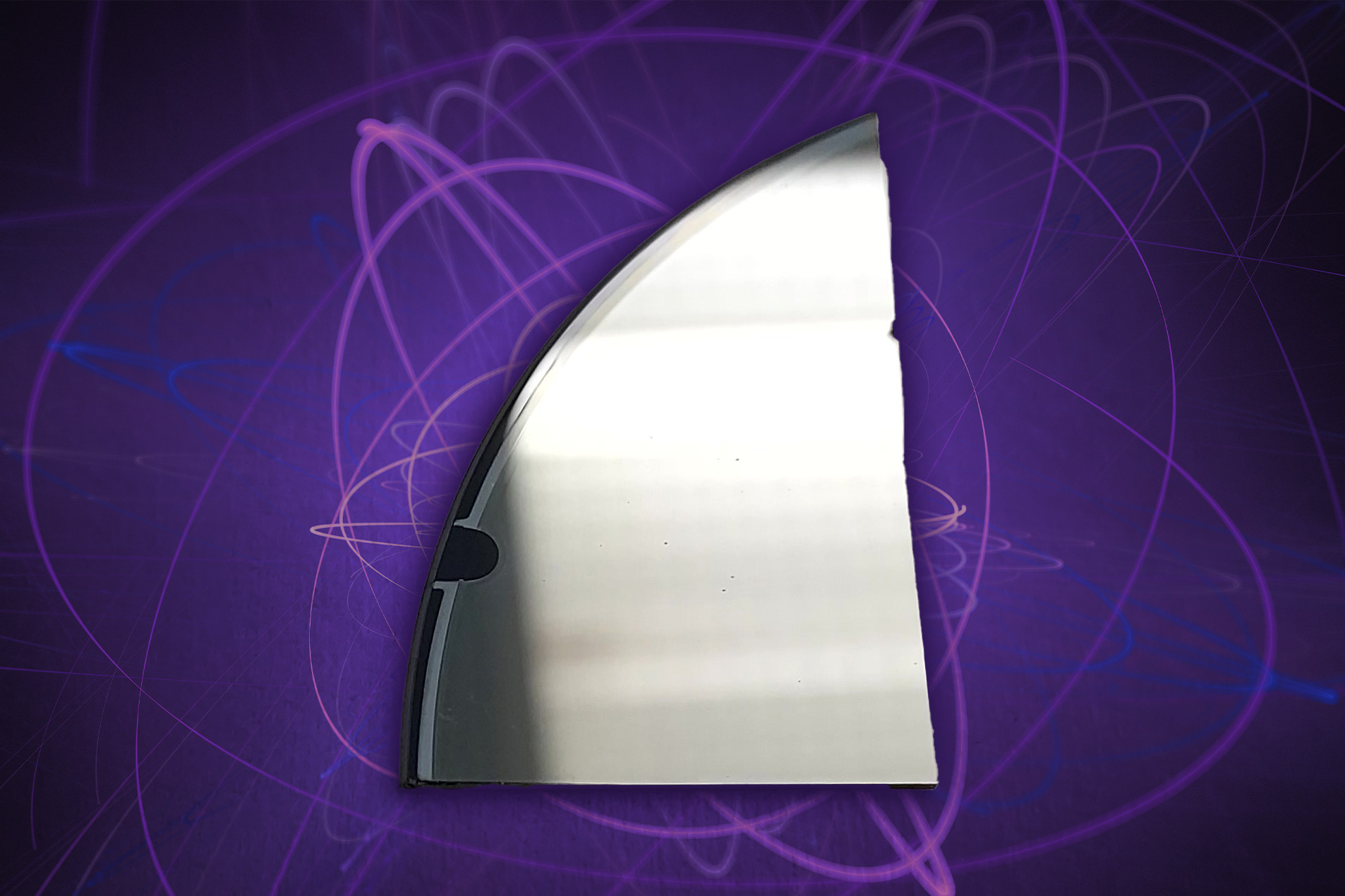

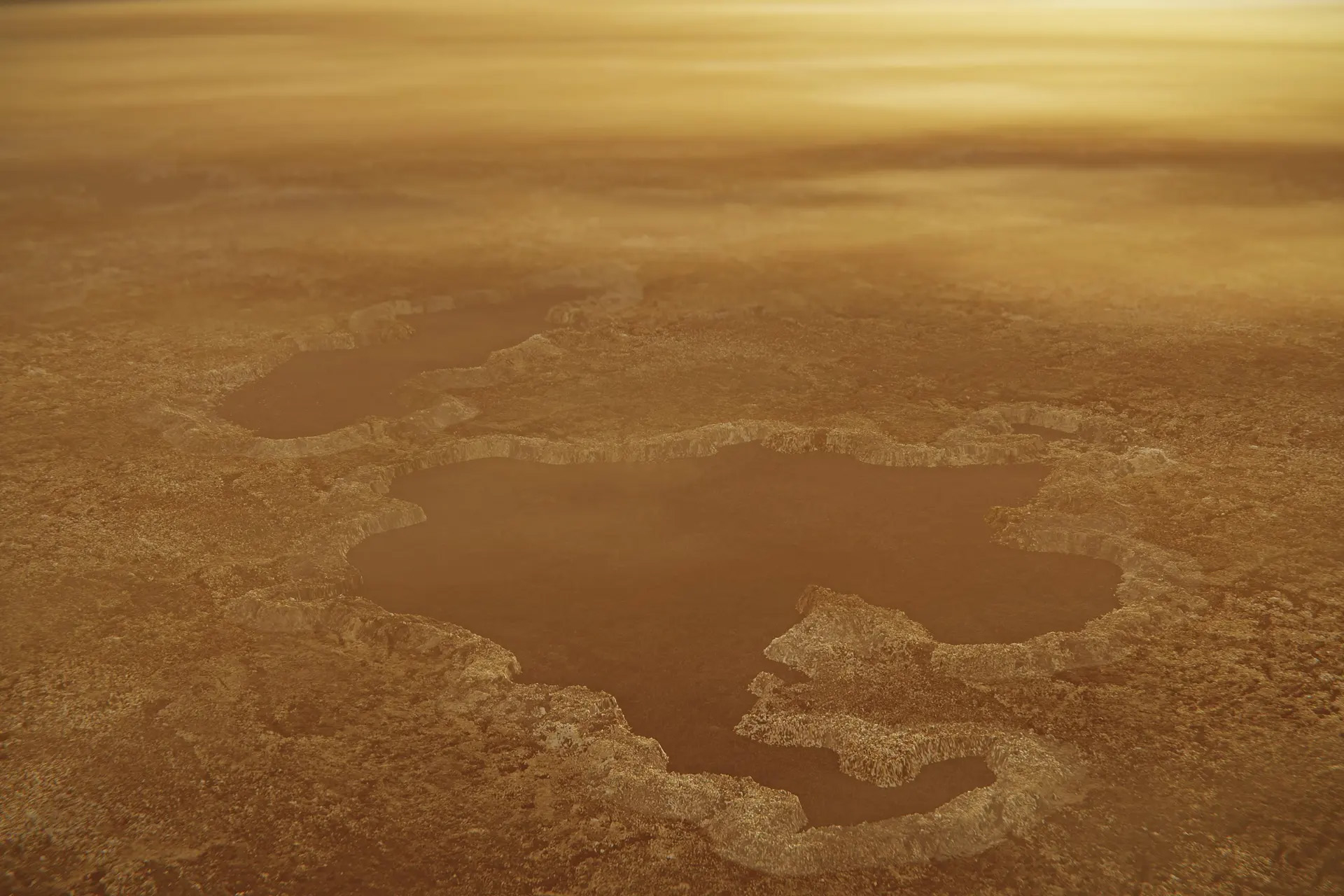

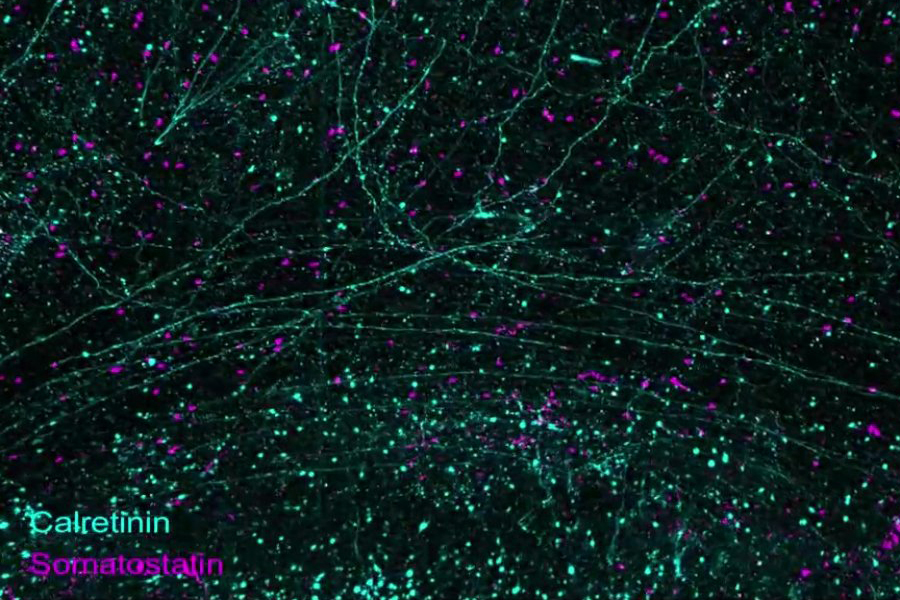

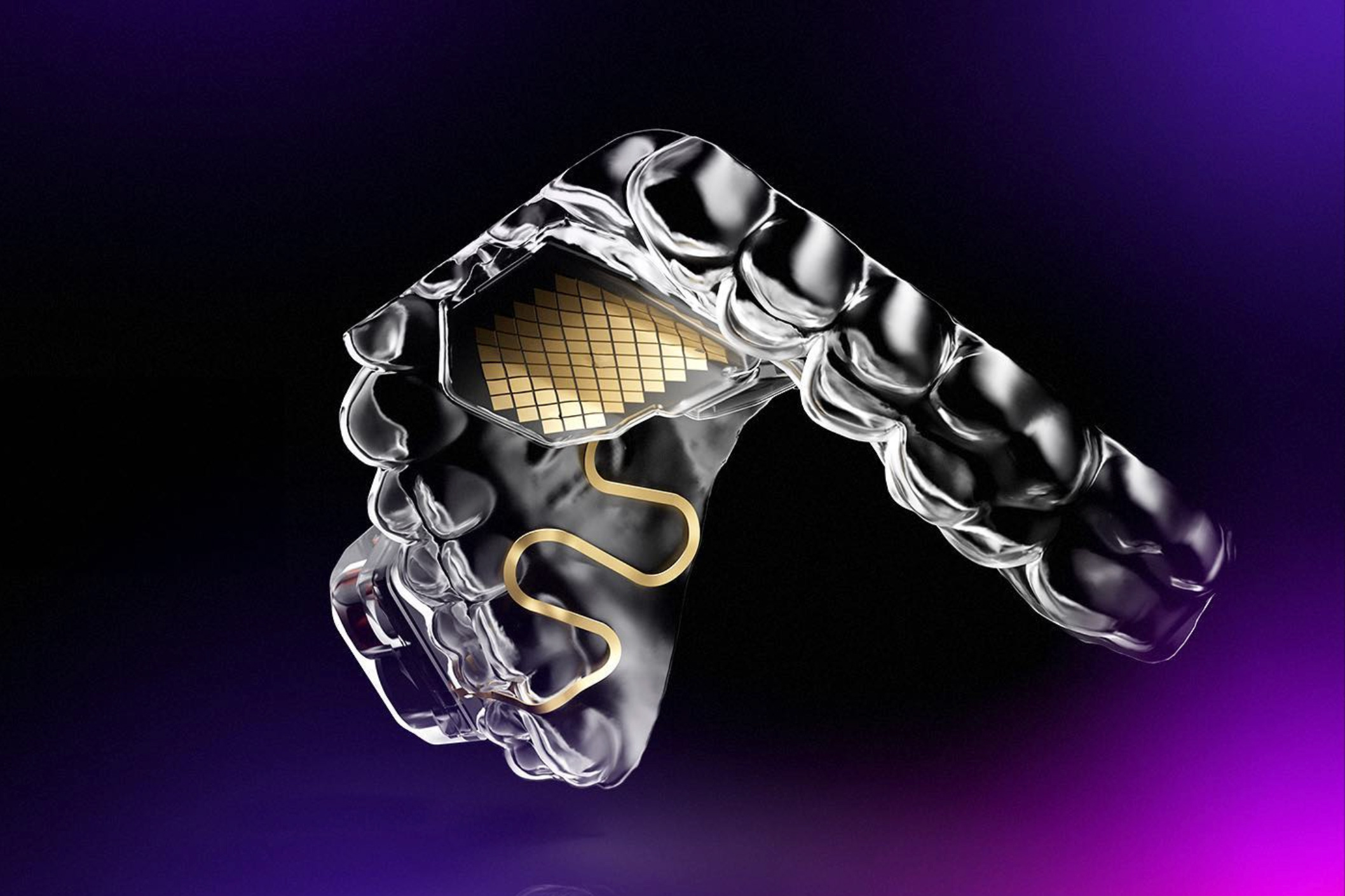

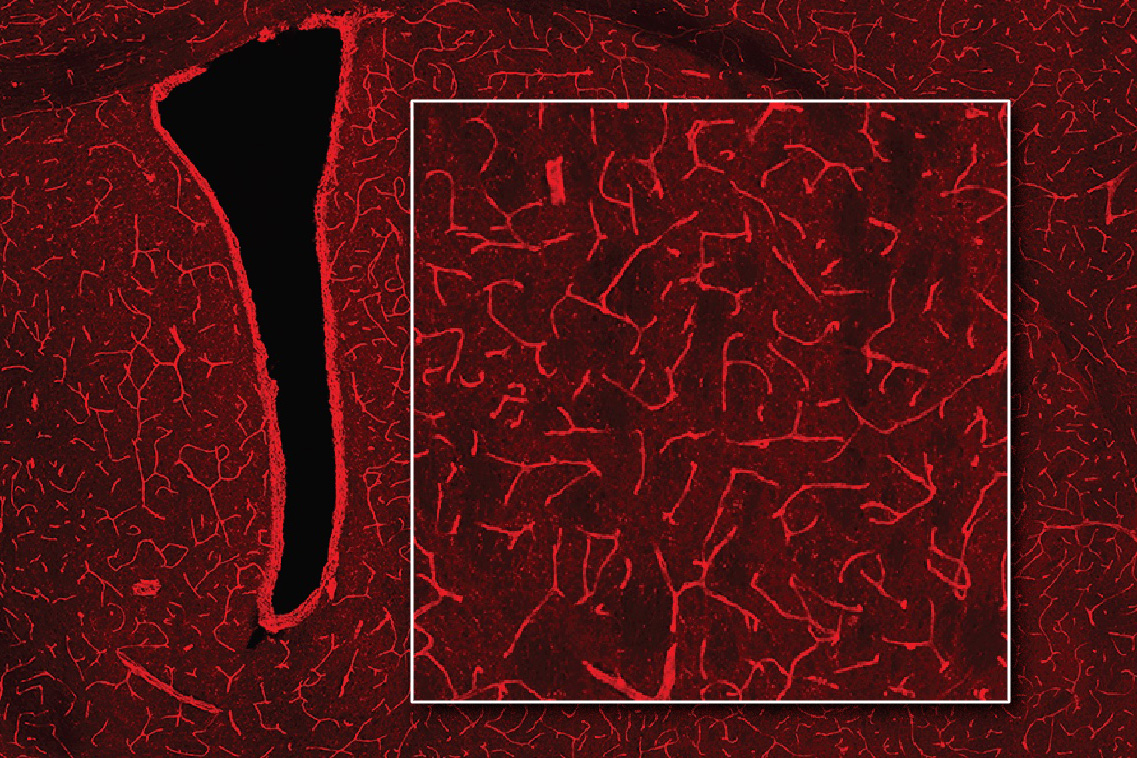

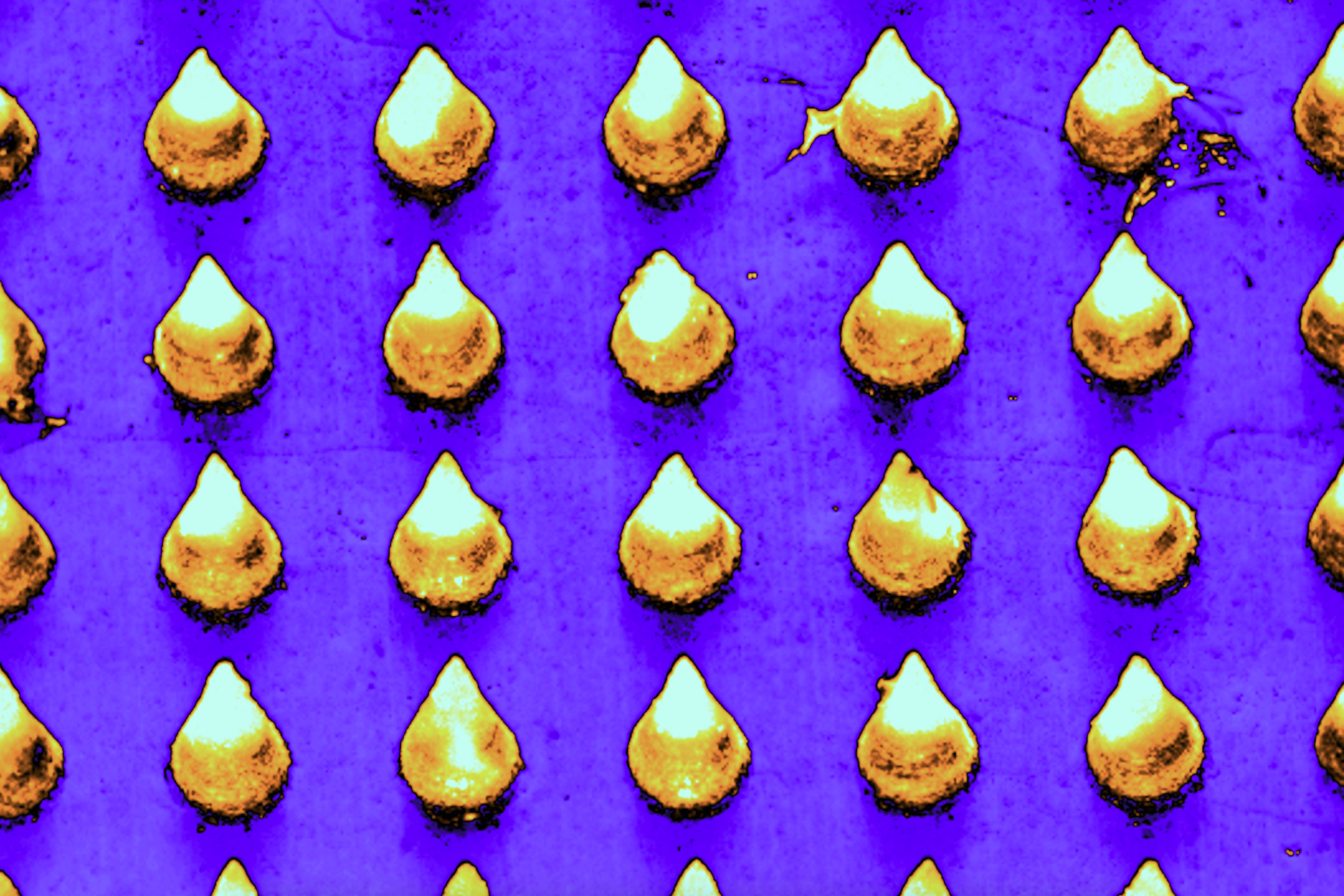

A wet, open-loop marine scrubber is a huge, metal, vertical tank installed in a ship’s exhaust stack, above the engines. Inside, seawater drawn from the ocean is sprayed through a series of nozzles downward to wash the hot exhaust gases as they exit the engines.

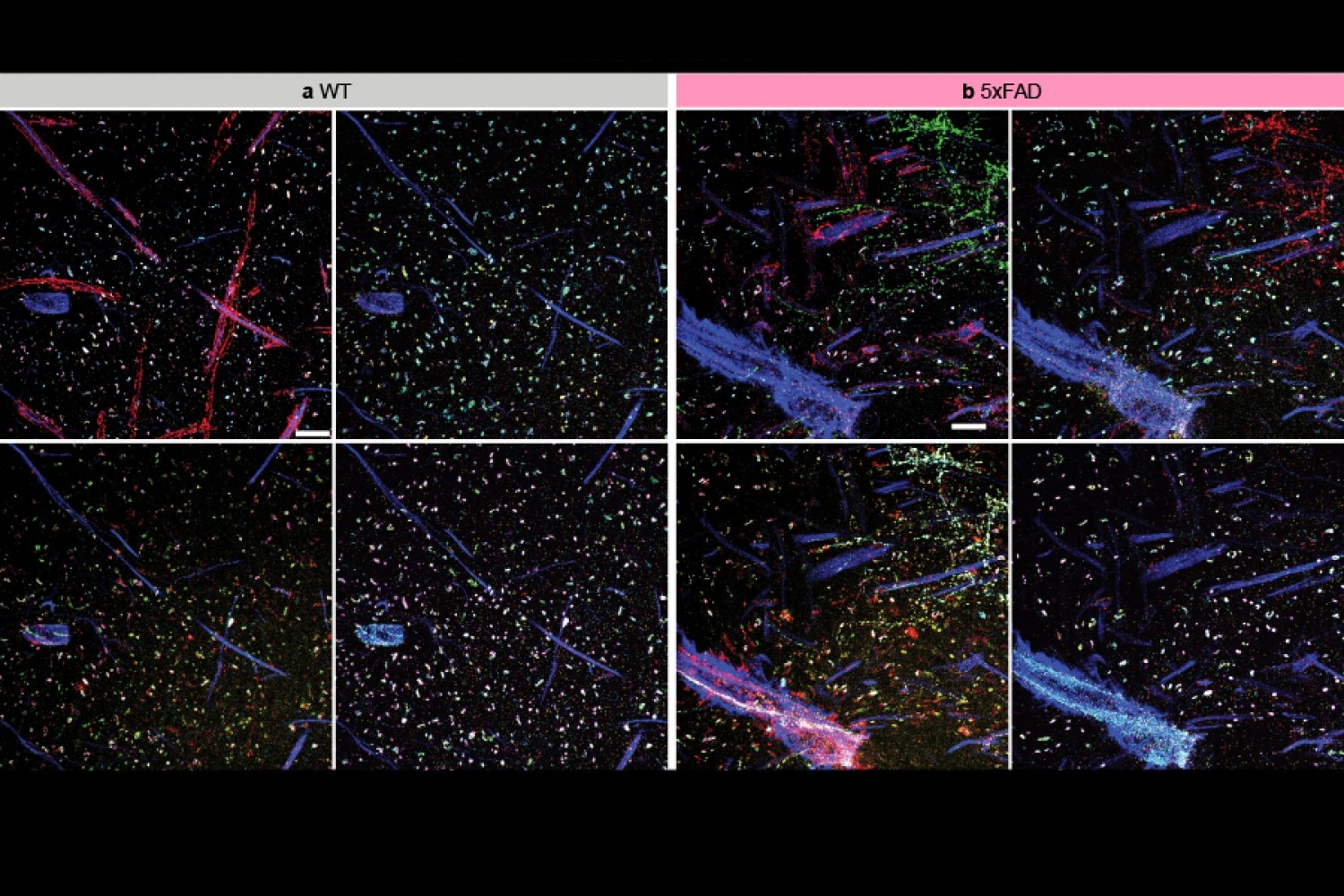

The seawater interacts with sulfur dioxide in the exhaust, converting it to sulfates — water-soluble, environmentally benign compounds that naturally occur in seawater. The washwater is released back into the ocean, while the cleaned exhaust escapes to the atmosphere with little to no sulfur dioxide emissions.

But the acidic washwater can contain other combustion byproducts like heavy metals, so scientists wondered if scrubbers were comparable, from a holistic environmental point of view, to burning low-sulfur fuels.

Several studies explored toxicity of washwater and fuel system pollution, but none painted a full picture.

The researchers set out to fill that scientific gap.

A “well-to-wake” analysis

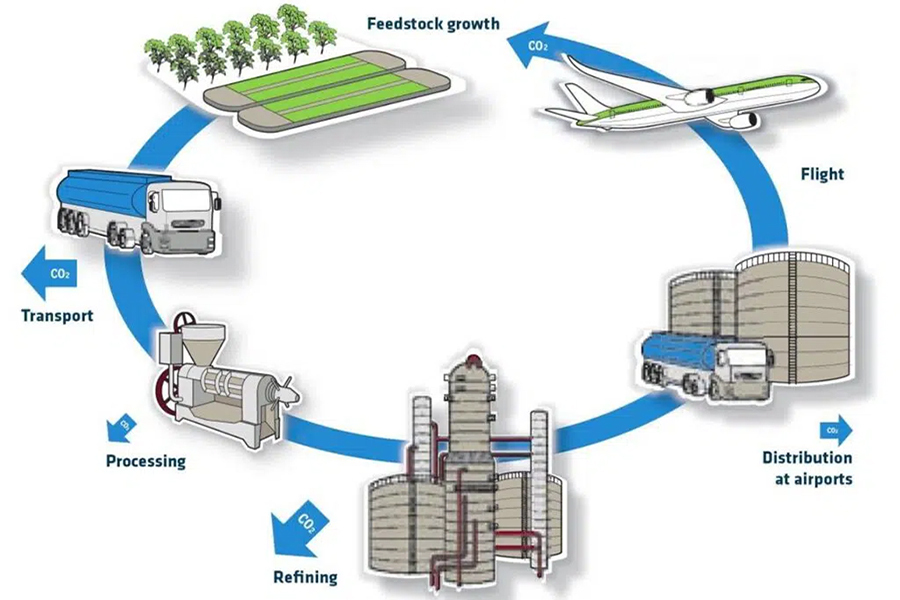

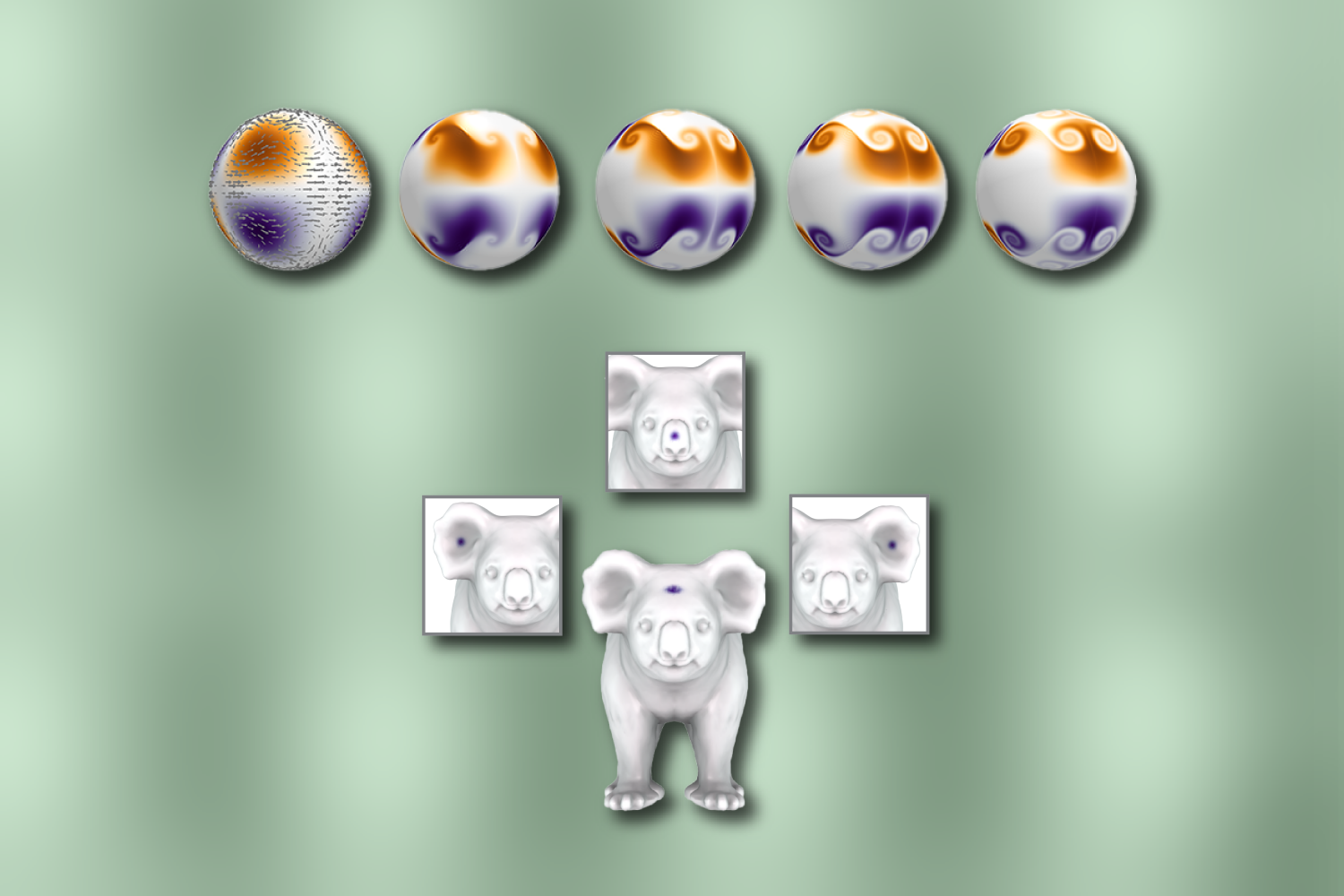

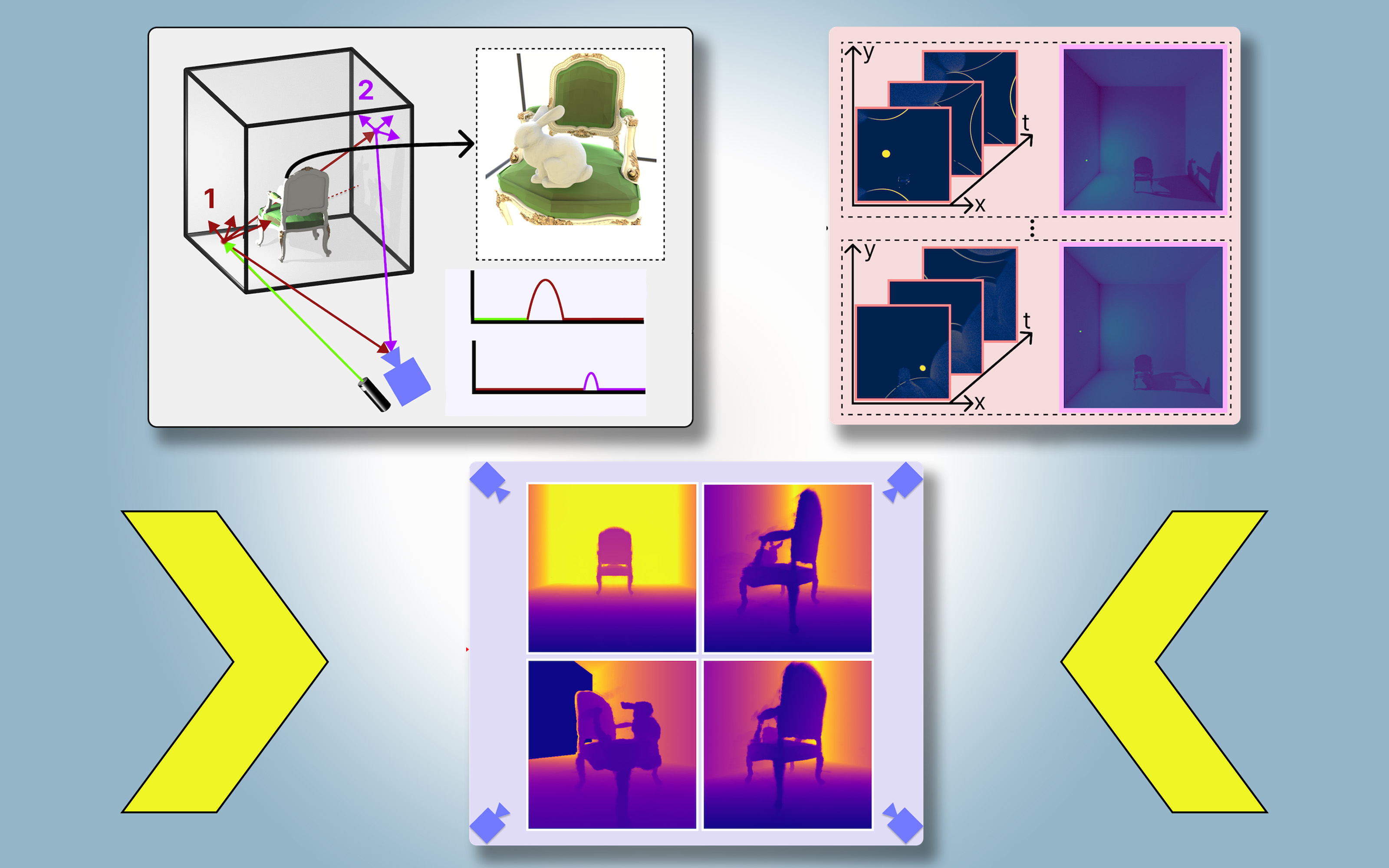

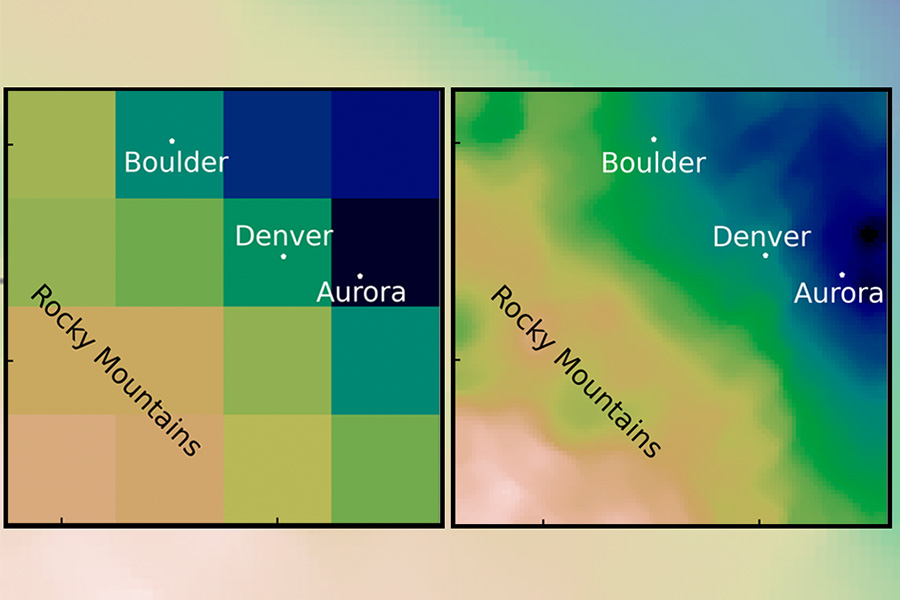

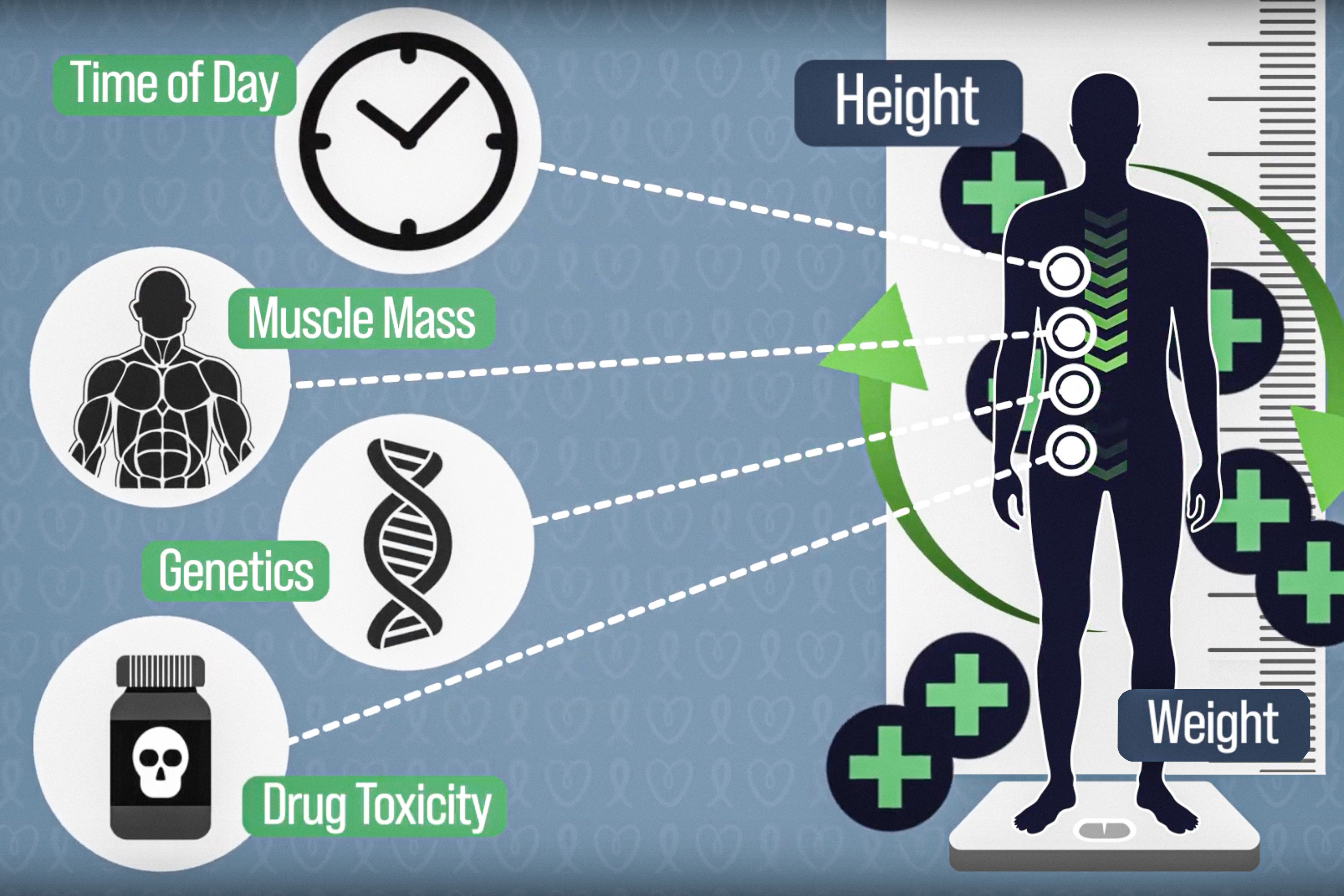

The team conducted a lifecycle assessment using a global environmental database on production and transport of fossil fuels, such as heavy fuel oil, marine gas oil, and very-low sulfur fuel oil. Considering the entire lifecycle of each fuel is key, since producing low-sulfur fuel requires extra processing steps in the refinery, causing additional emissions of greenhouse gases and particulate matter.

“If we just look at everything that happens before the fuel is bunkered onboard the vessel, heavy fuel oil is significantly more low-impact, environmentally, than low-sulfur fuels,” she says.

The researchers also collaborated with a scrubber manufacturer to obtain detailed information on all materials, production processes, and transportation steps involved in marine scrubber fabrication and installation.

“If you consider that the scrubber has a lifetime of about 20 years, the environmental impacts of producing the scrubber over its lifetime are negligible compared to producing heavy fuel oil,” she adds.

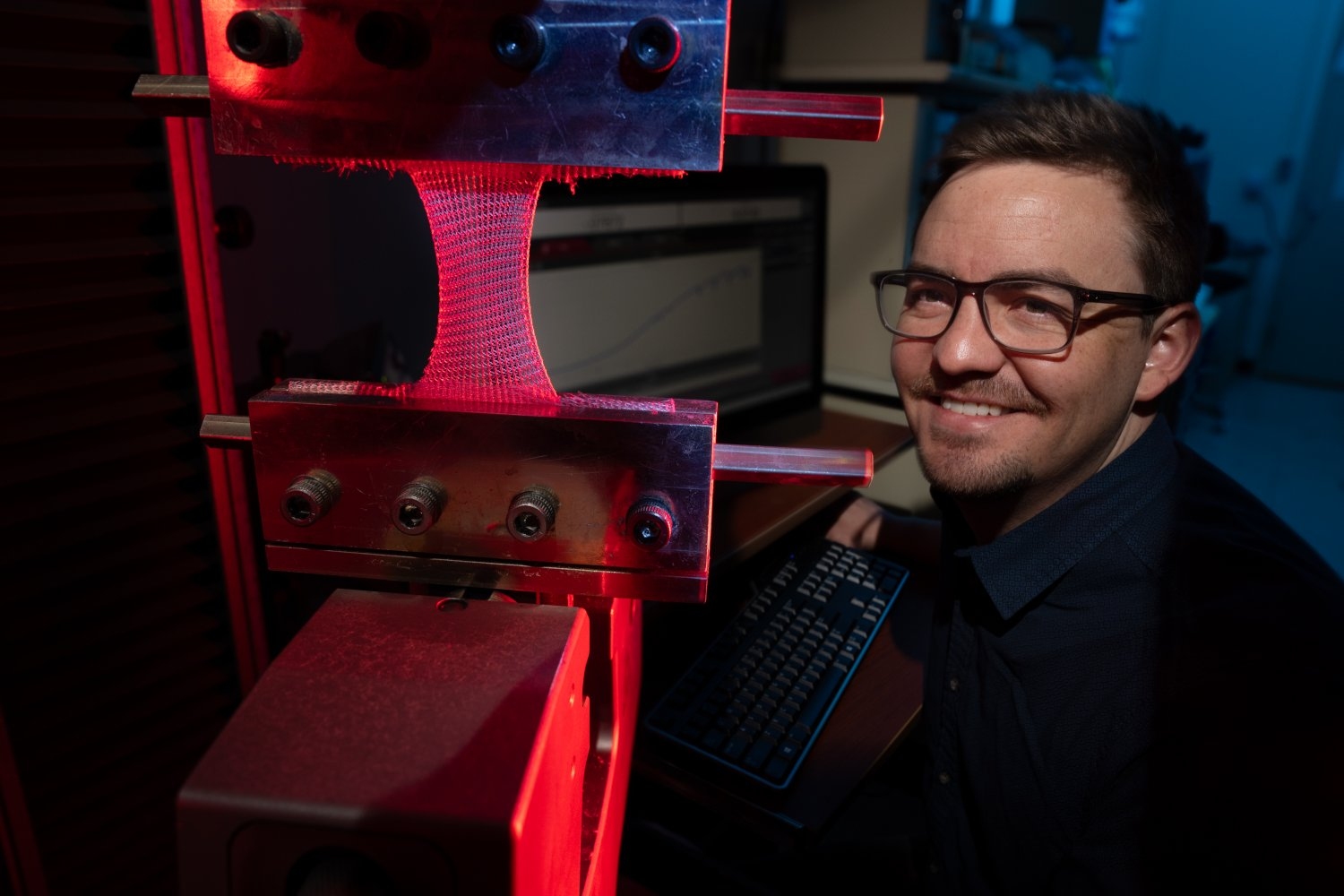

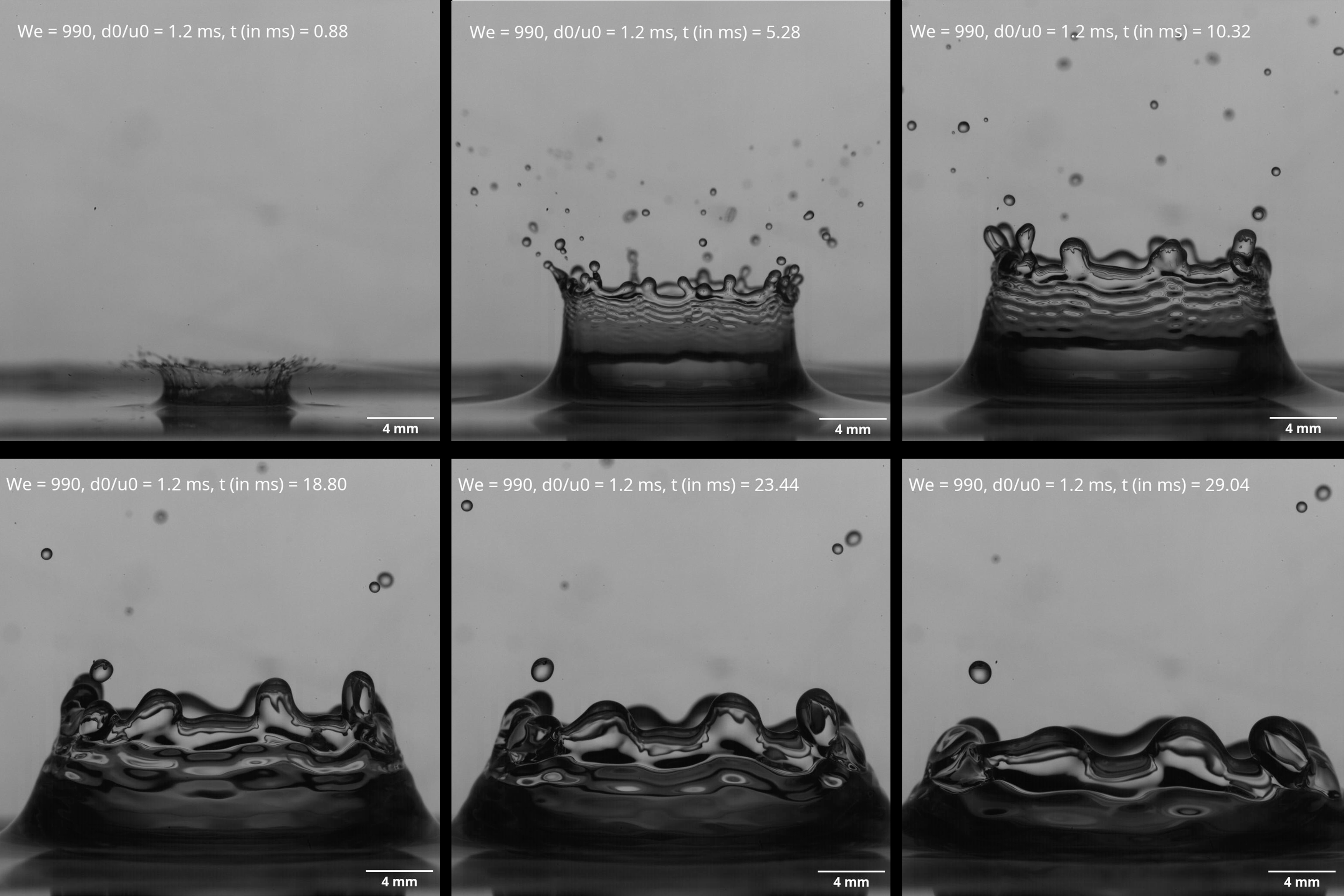

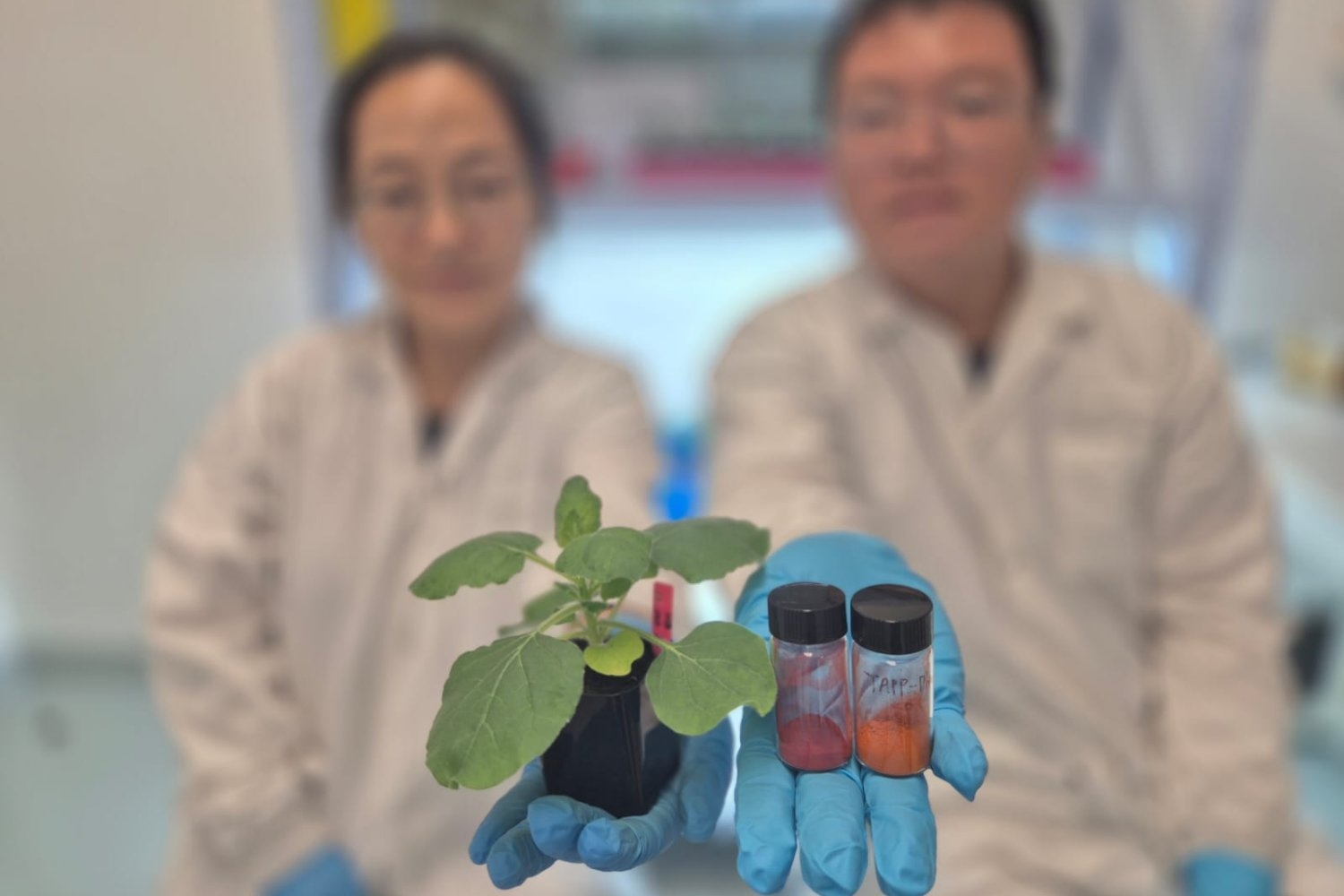

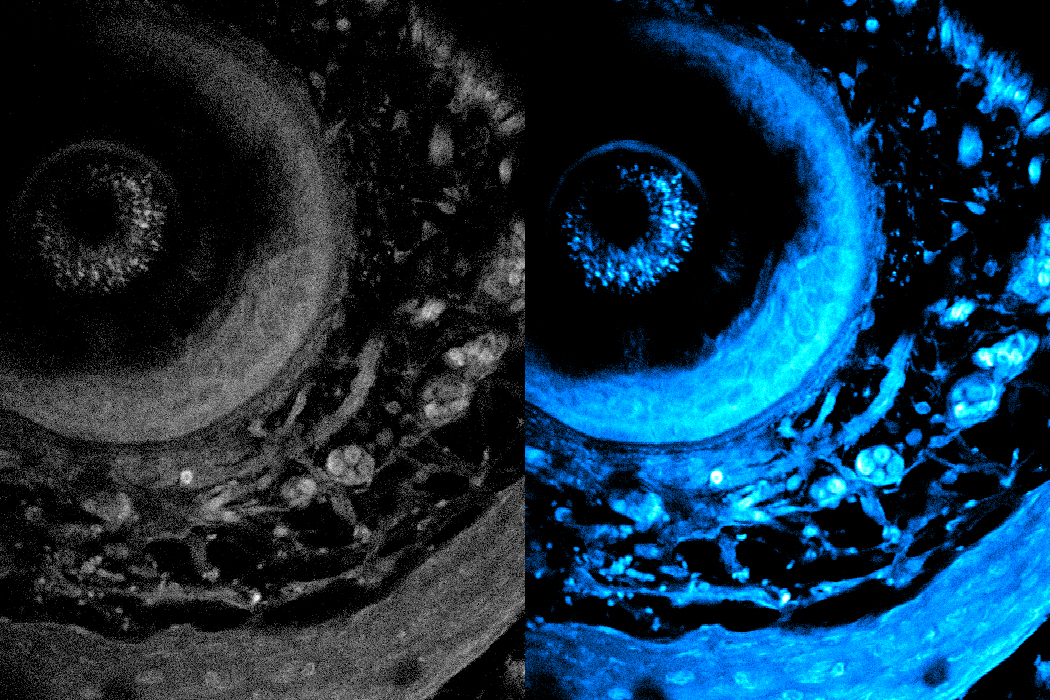

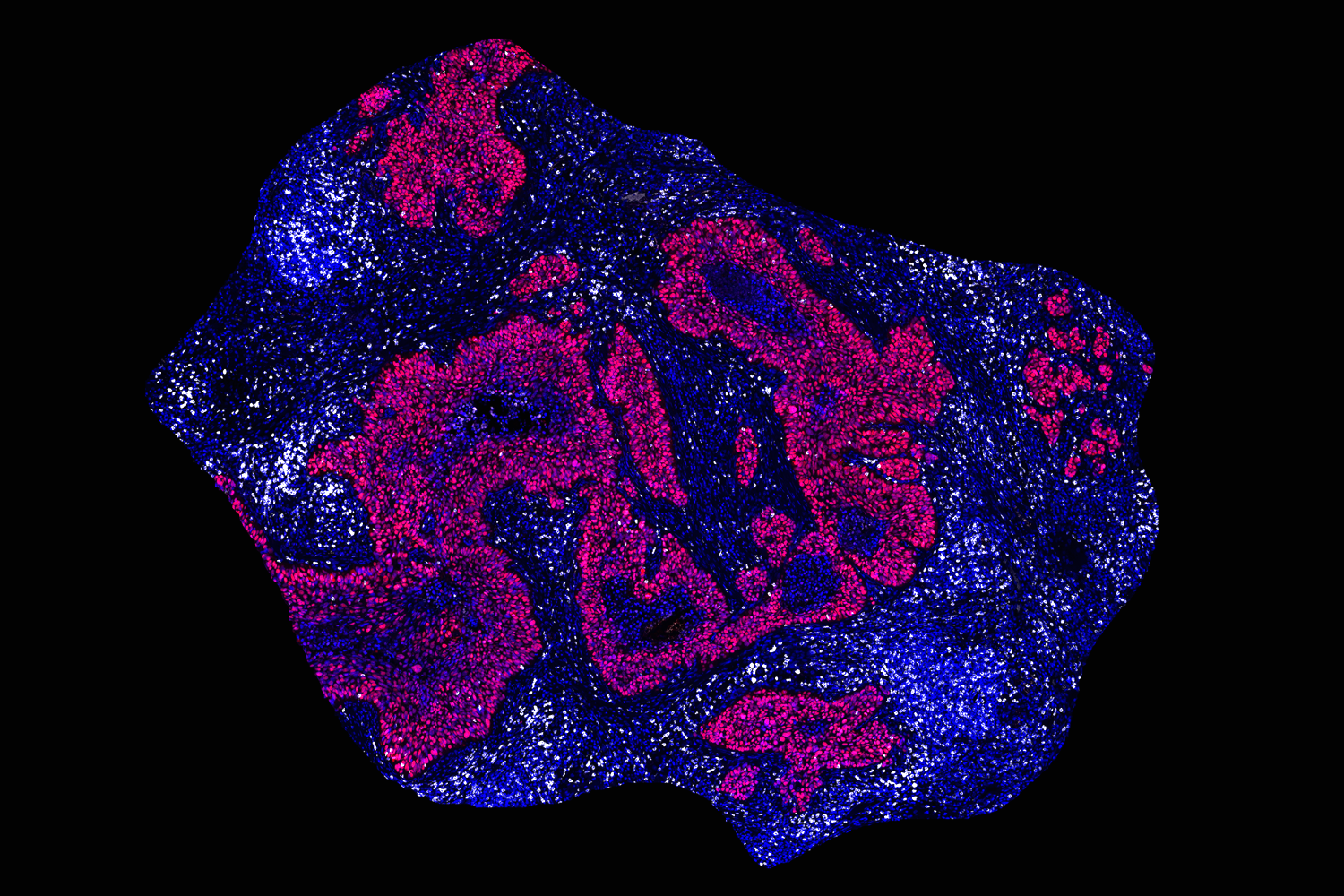

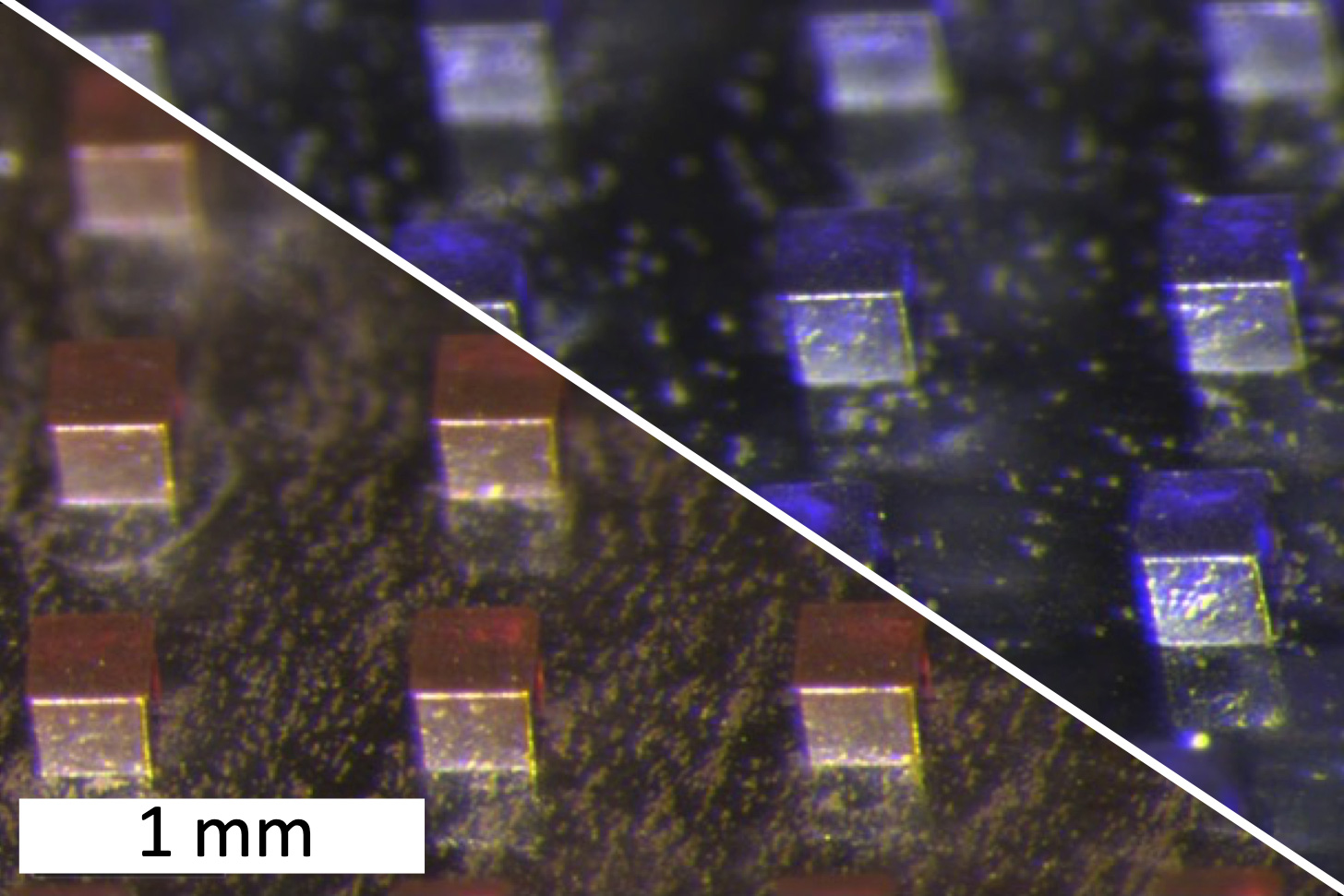

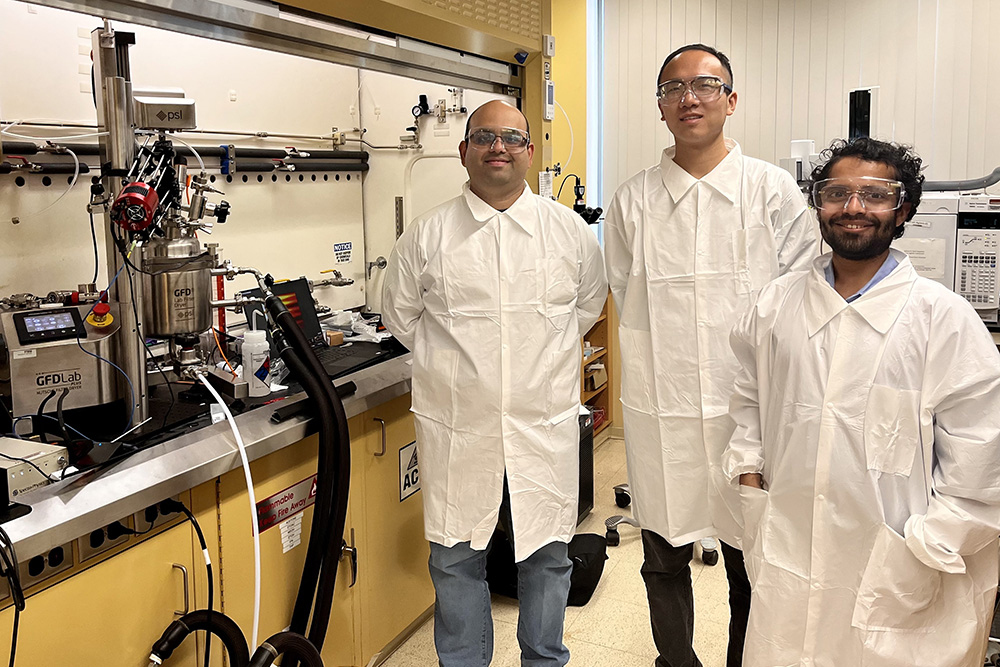

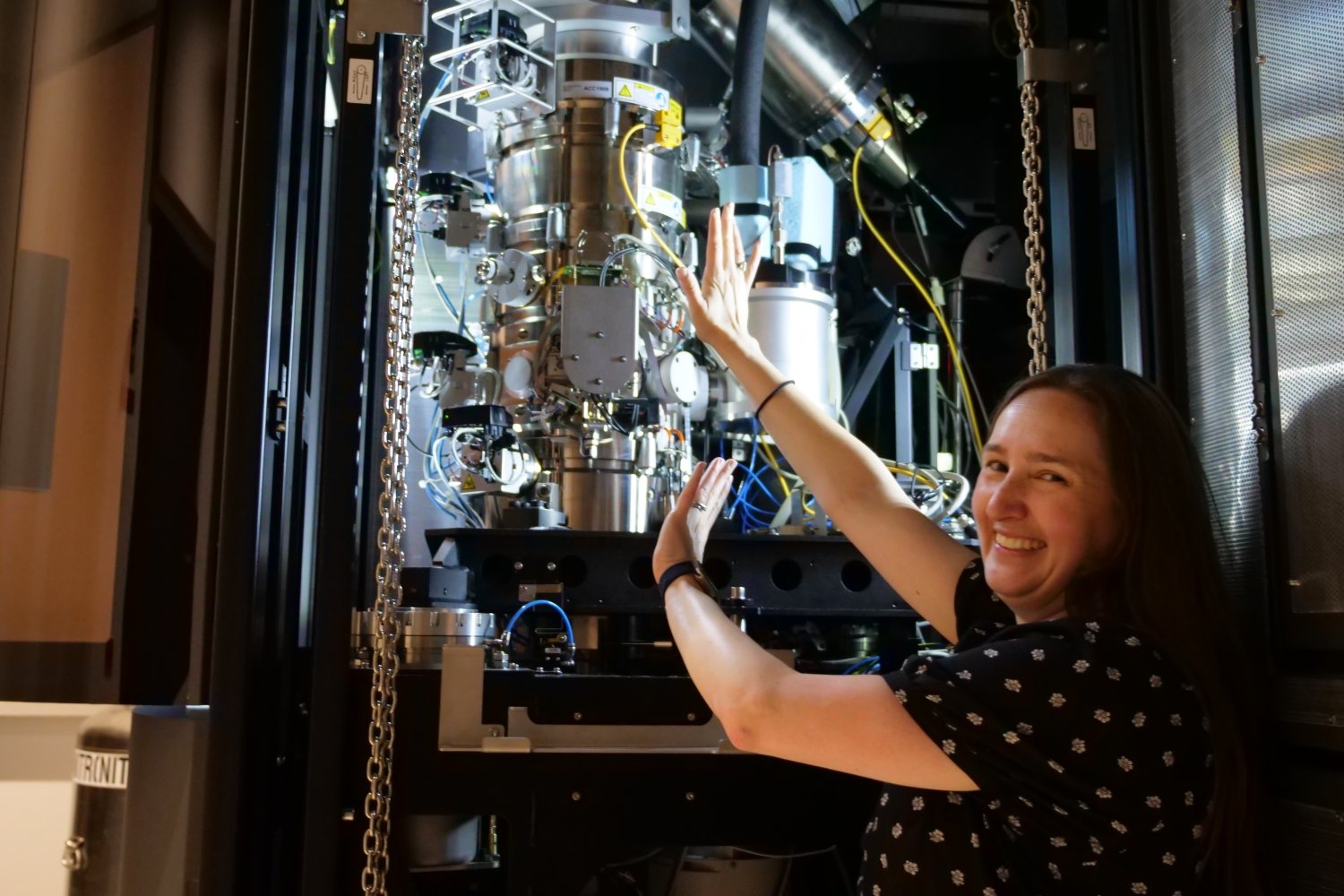

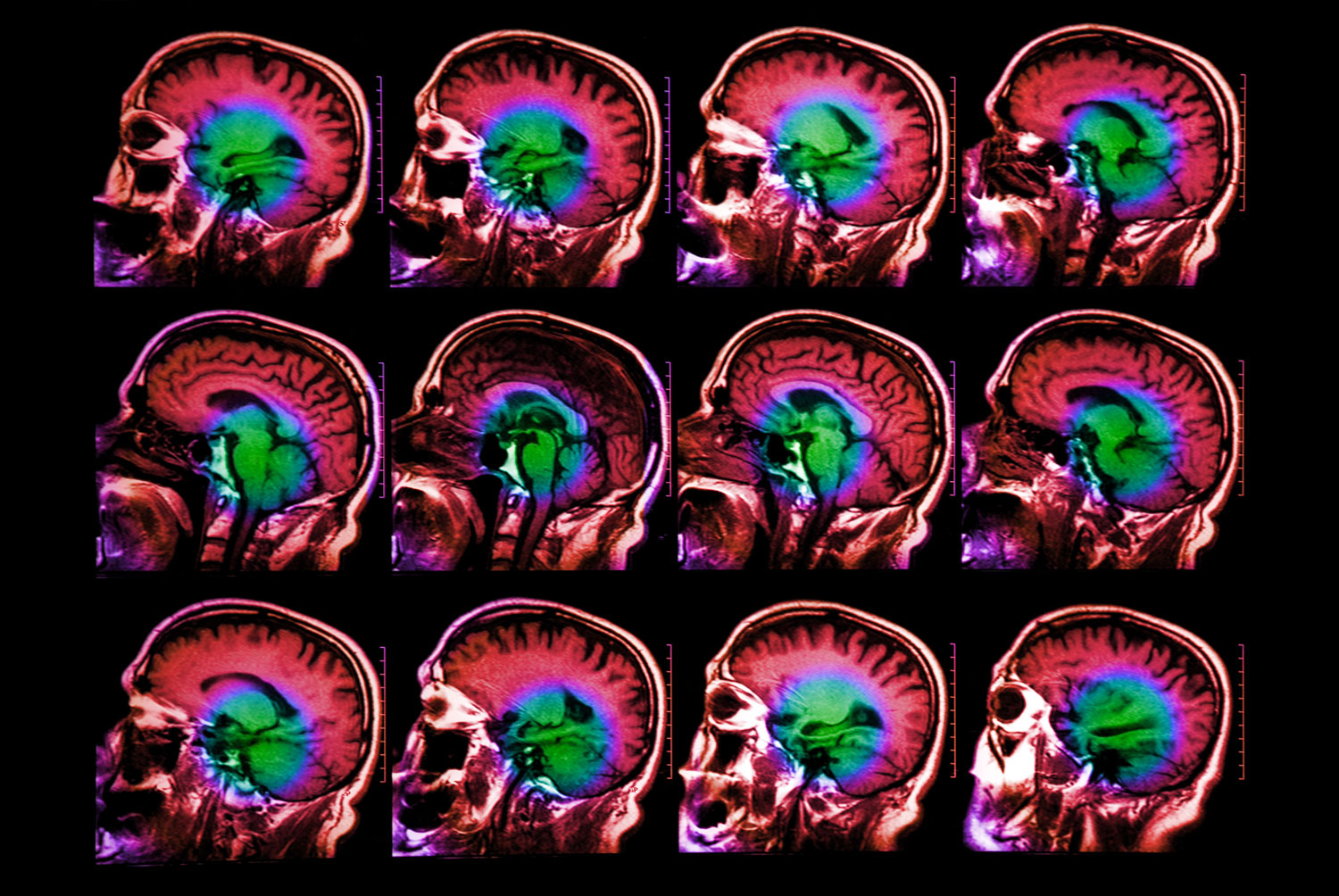

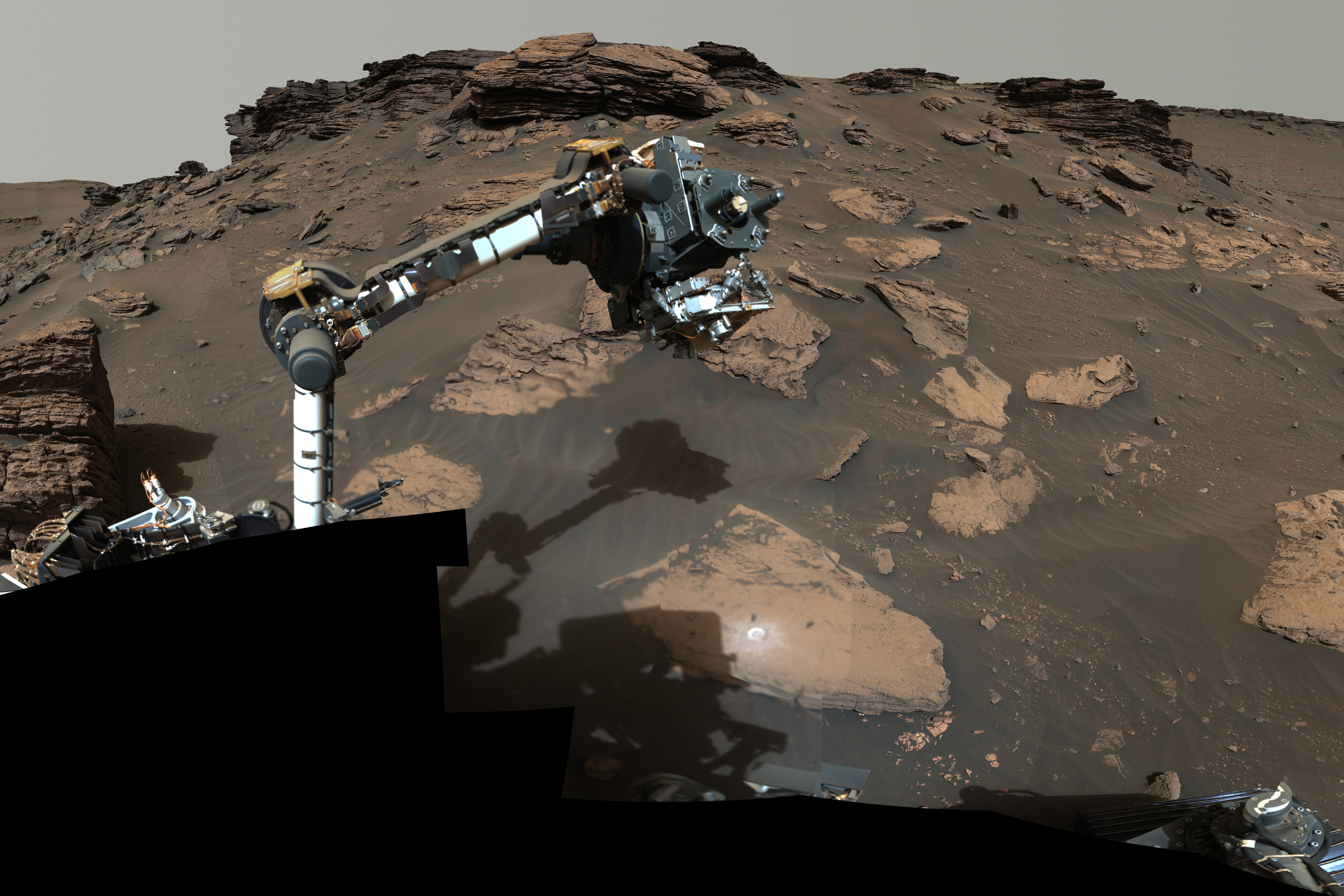

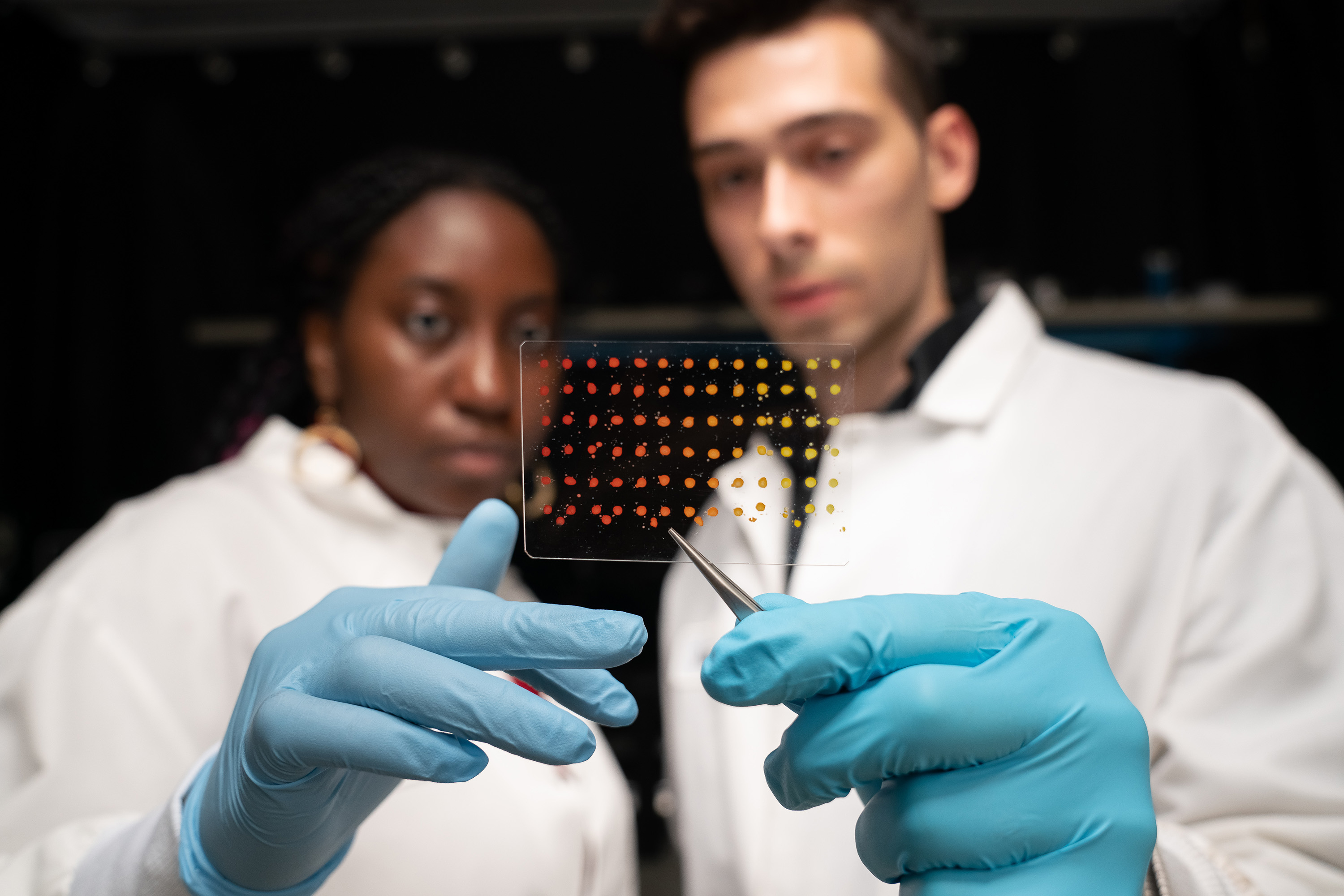

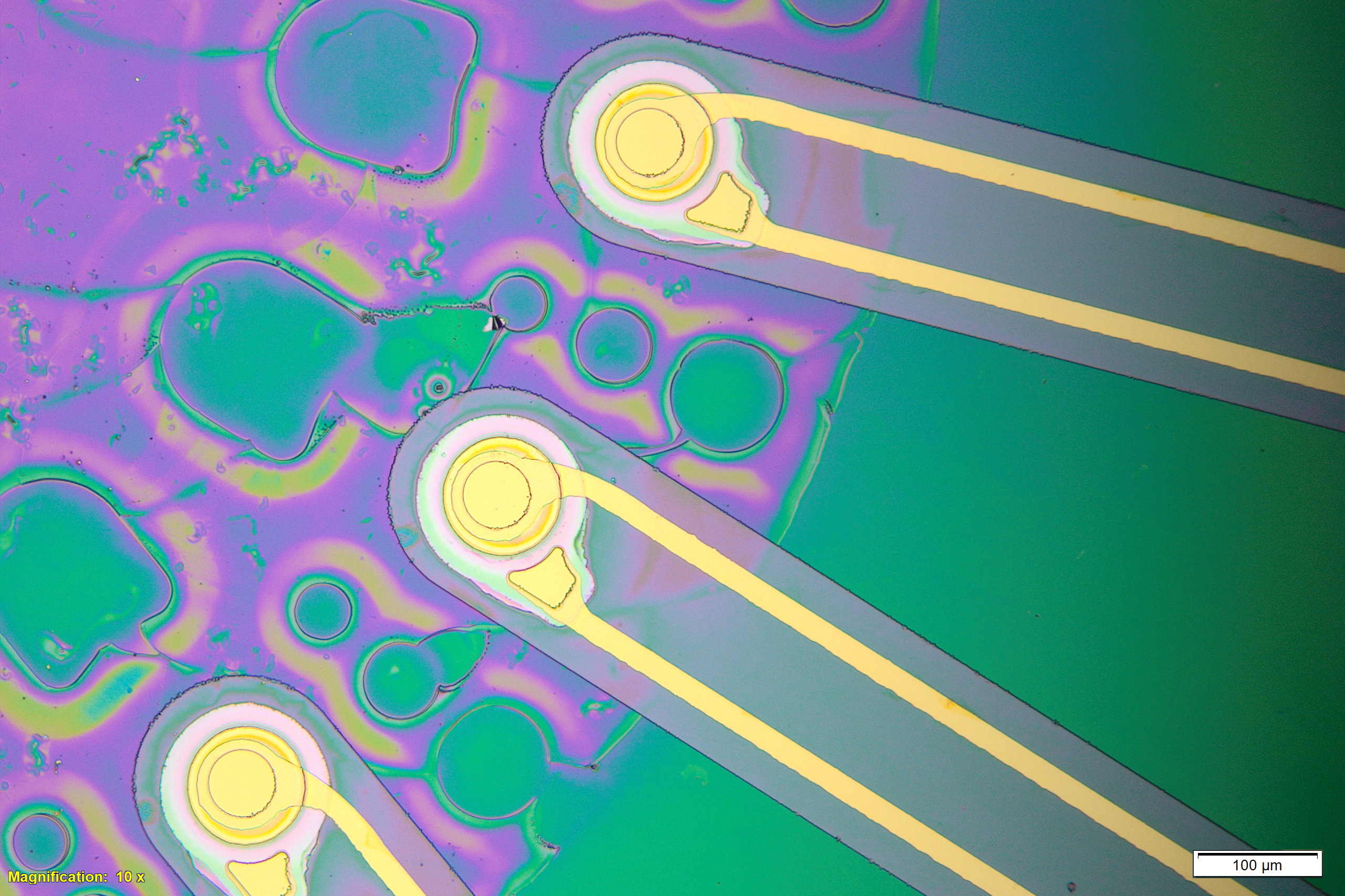

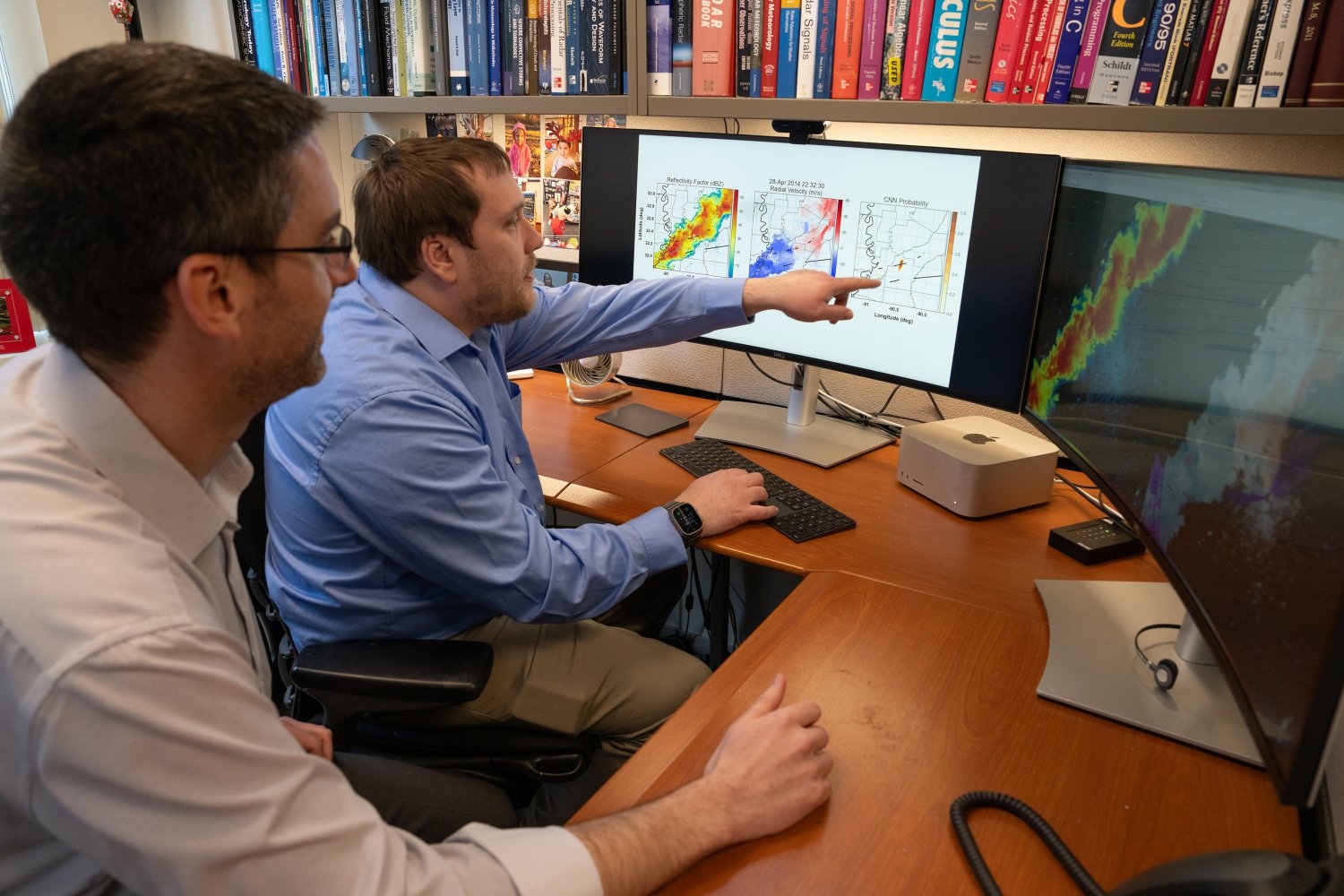

For the final piece, Stathatou spent a week onboard a bulk carrier vessel in China to measure emissions and gather seawater and washwater samples. The ship burned heavy fuel oil with a scrubber and low-sulfur fuels under similar ocean conditions and engine settings.

Collecting these onboard data was the most challenging part of the study.

“All the safety gear, combined with the heat and the noise from the engines on a moving ship, was very overwhelming,” she says.

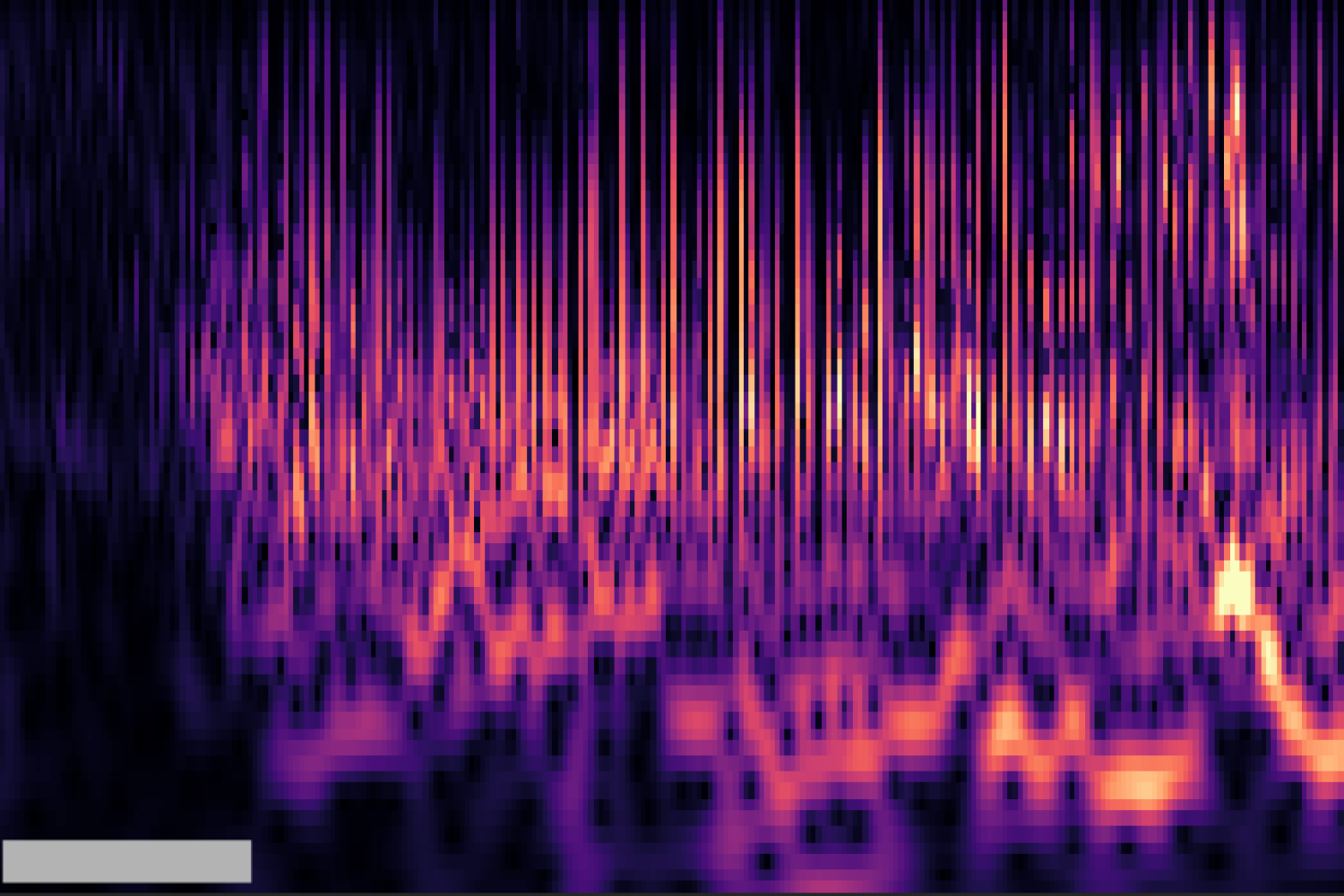

Their results showed that scrubbers reduce sulfur dioxide emissions by 97 percent, putting heavy fuel oil on par with low-sulfur fuels according to that measure. The researchers saw similar trends for emissions of other pollutants like carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide.

In addition, they tested washwater samples for more than 60 chemical parameters, including nitrogen, phosphorus, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and 23 metals.

The concentrations of chemicals regulated by the IMO were far below the organization’s requirements. For unregulated chemicals, the researchers compared the concentrations to the strictest limits for industrial effluents from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and European Union.

Most chemical concentrations were at least an order of magnitude below these requirements.

In addition, since washwater is diluted thousands of times as it is dispersed by a moving vessel, the concentrations of such chemicals would be even lower in the open ocean.

These findings suggest that the use of scrubbers with heavy fuel oil can be considered as equal to or more environmentally friendly than low-sulfur fuels across many of the impact categories the researchers studied.

“This study demonstrates the scientific complexity of the waste stream of scrubbers. Having finally conducted a multiyear, comprehensive, and peer-reviewed study, commonly held fears and assumptions are now put to rest,” says Scott Bergeron, managing director at Oldendorff Carriers and co-author of the study.

“This first-of-its-kind study on a well-to-wake basis provides very valuable input to ongoing discussion at the IMO,” adds Thomas Klenum, executive vice president of innovation and regulatory affairs at the Liberian Registry, emphasizing the need “for regulatory decisions to be made based on scientific studies providing factual data and conclusions.”

Ultimately, this study shows the importance of incorporating lifecycle assessments into future environmental impact reduction policies, Stathatou says.

“There is all this discussion about switching to alternative fuels in the future, but how green are these fuels? We must do our due diligence to compare them equally with existing solutions to see the costs and benefits,” she adds.

This study was supported, in part, by Oldendorff Carriers.

© Photo: Courtesy of Patricia Stathatou