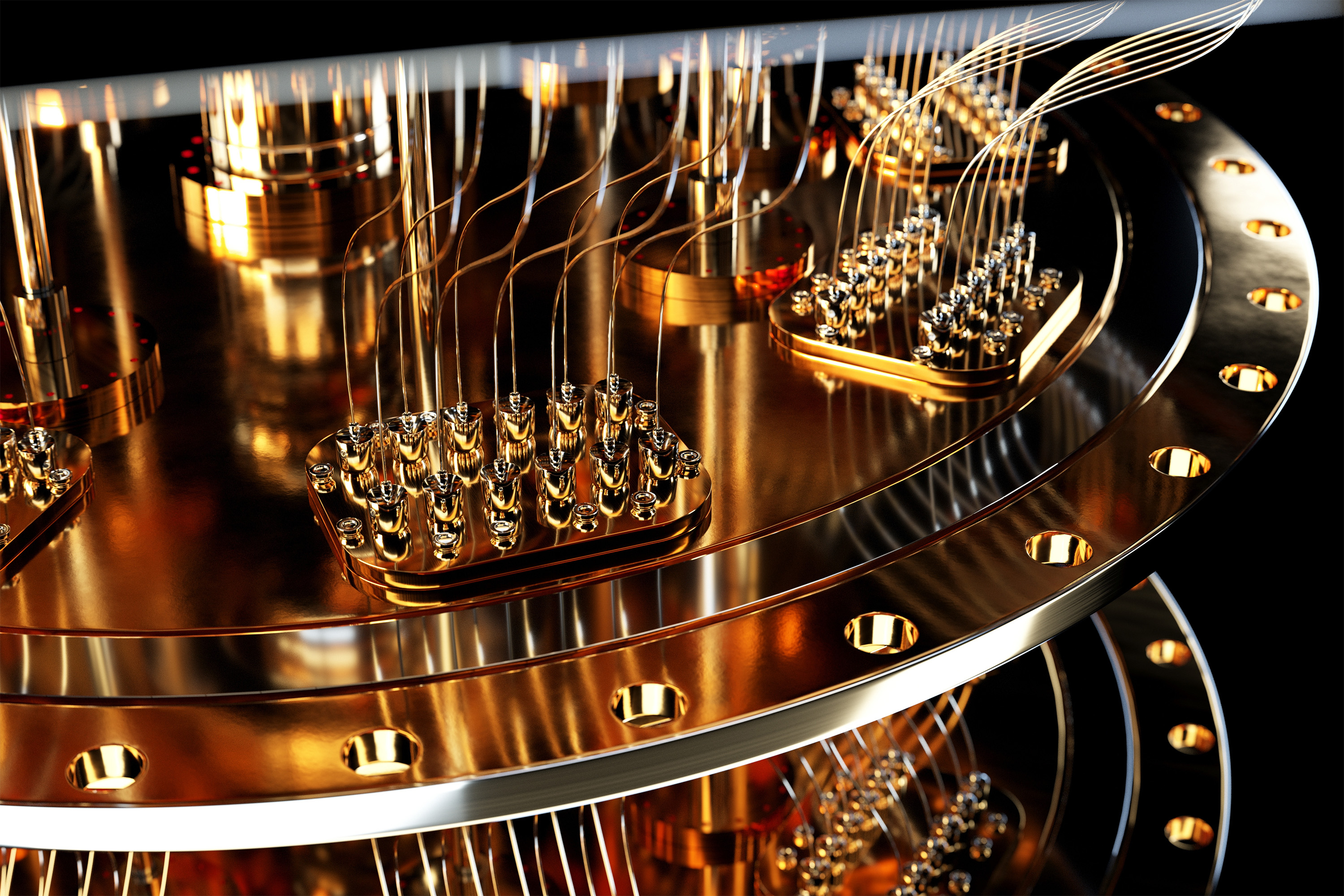

Supersize me

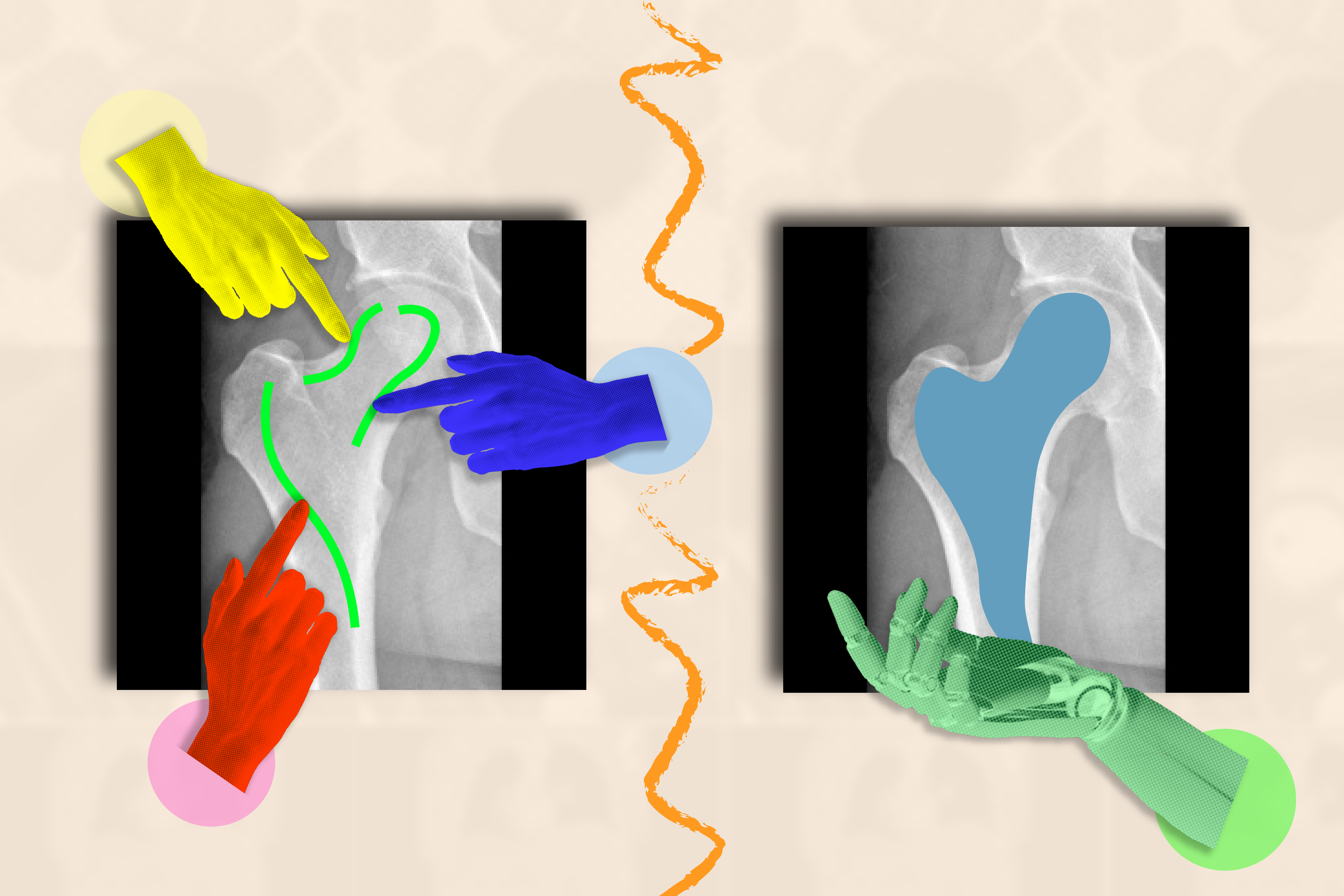

Well into the late 19th century, the U.S. retail sector was overwhelmingly local, consisting of small, independent merchants throughout the country. That started changing after Sears and Roebuck’s famous catalog became popular, allowing the firm to grow, while a rival, Montgomery Ward, also expanded. By the 1930s, the U.S. had 130,000 chain stores, topped by Atlantic and Pacific supermarkets (the A&P), with over 15,000 stores.

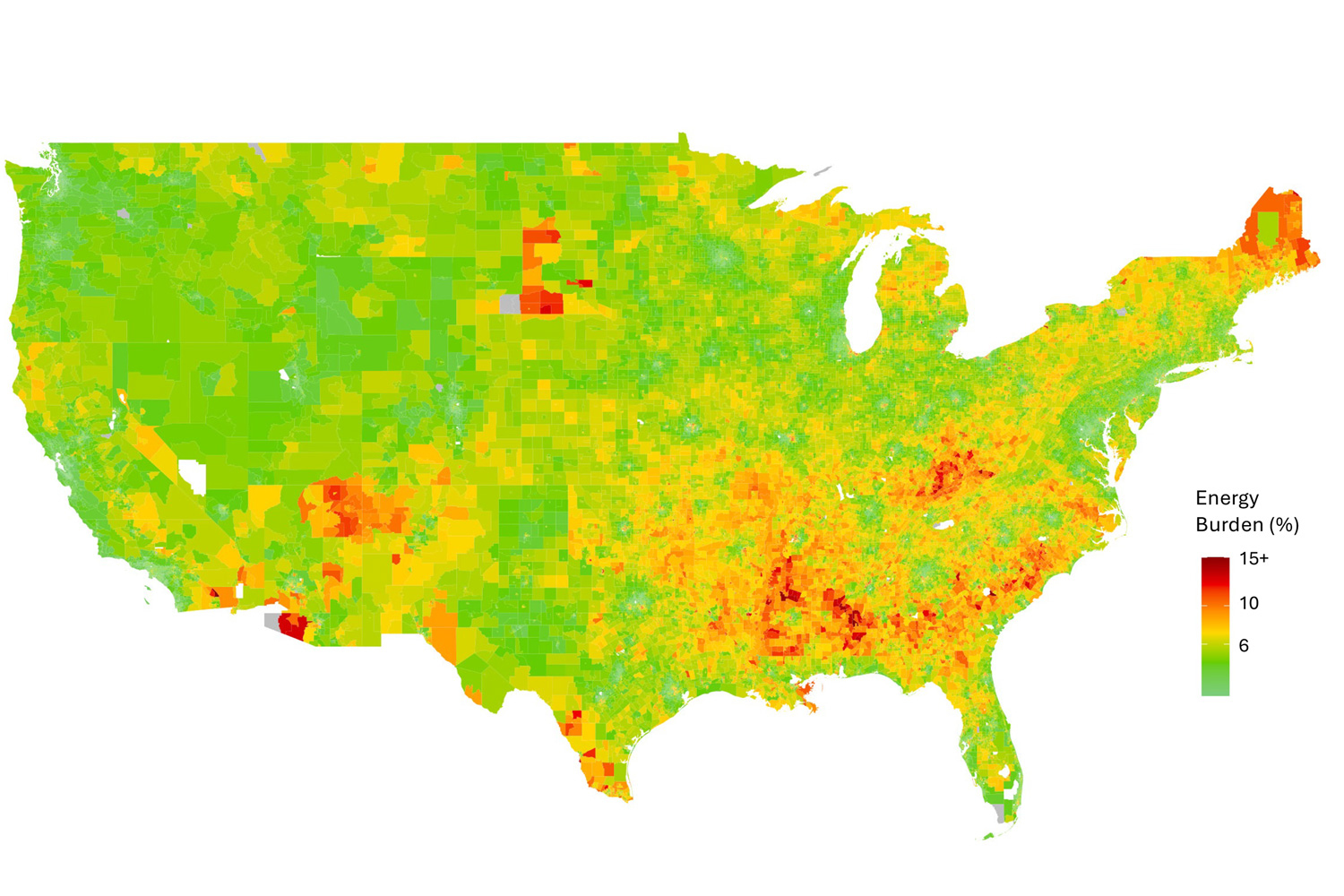

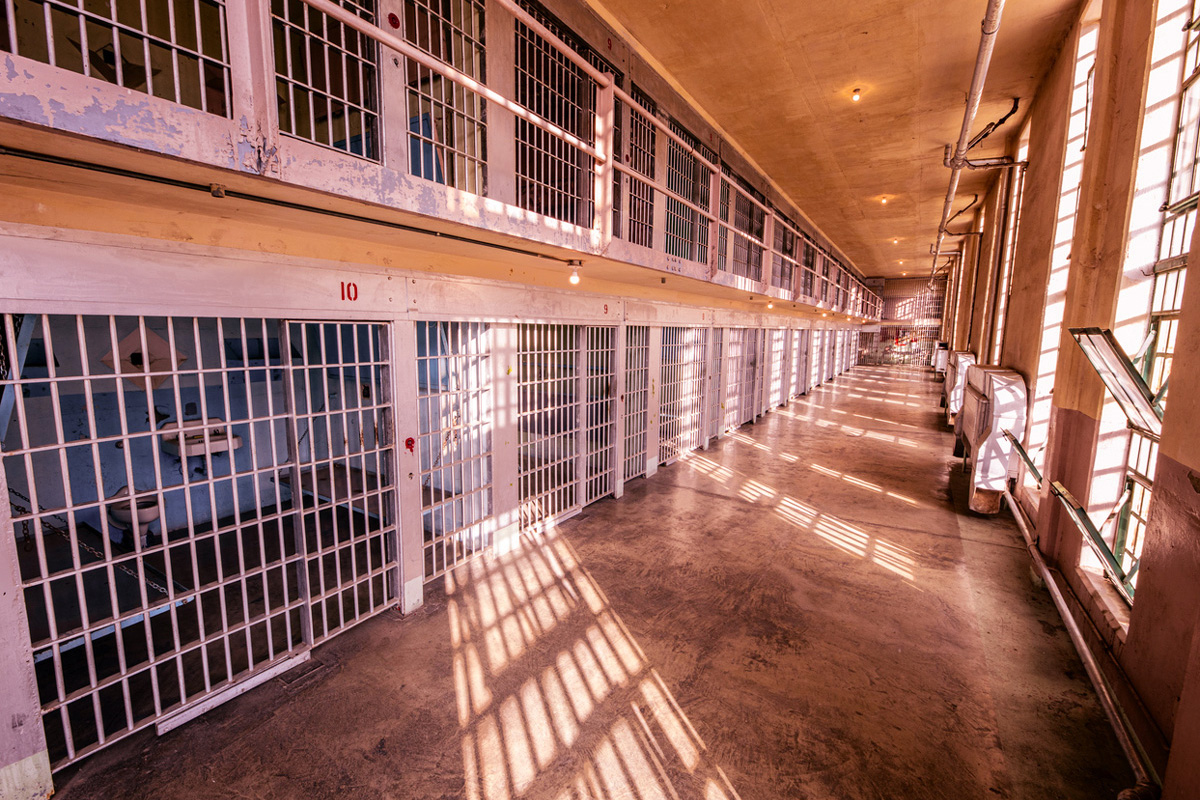

A century onward, the U.S. retail landscape is dominated by retail giants. Today, 90 percent of Americans live within 10 miles of a Walmart, while five of the country’s 10 biggest employers — Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, Kroger, and Target— are retailers. Two others in the top 10, UPS and FedEx, are a major part of the retail economy.

The ubiquity of these big retailers, and the sheer extent of the U.S. shopping economy as a whole, is unusual compared to the country’s European counterparts. Domestic consumption plays an outsized role in driving growth in the United States, and credit plays a much larger role in supporting that consumption than in Europe. The U.S. has five times as much retail space per capita as Japan and the U.K., and 10 times as much as Germany. Unlike in Europe, shopping hours are largely unregulated.

How did this happen? To be sure, Walmart, Amazon, Target, and other massive chains have plenty of business acumen. But the full story involves a century or more of political tectonics and legal debates, which helped shape the size of U.S. retailing and the prominence of its large discount chains.

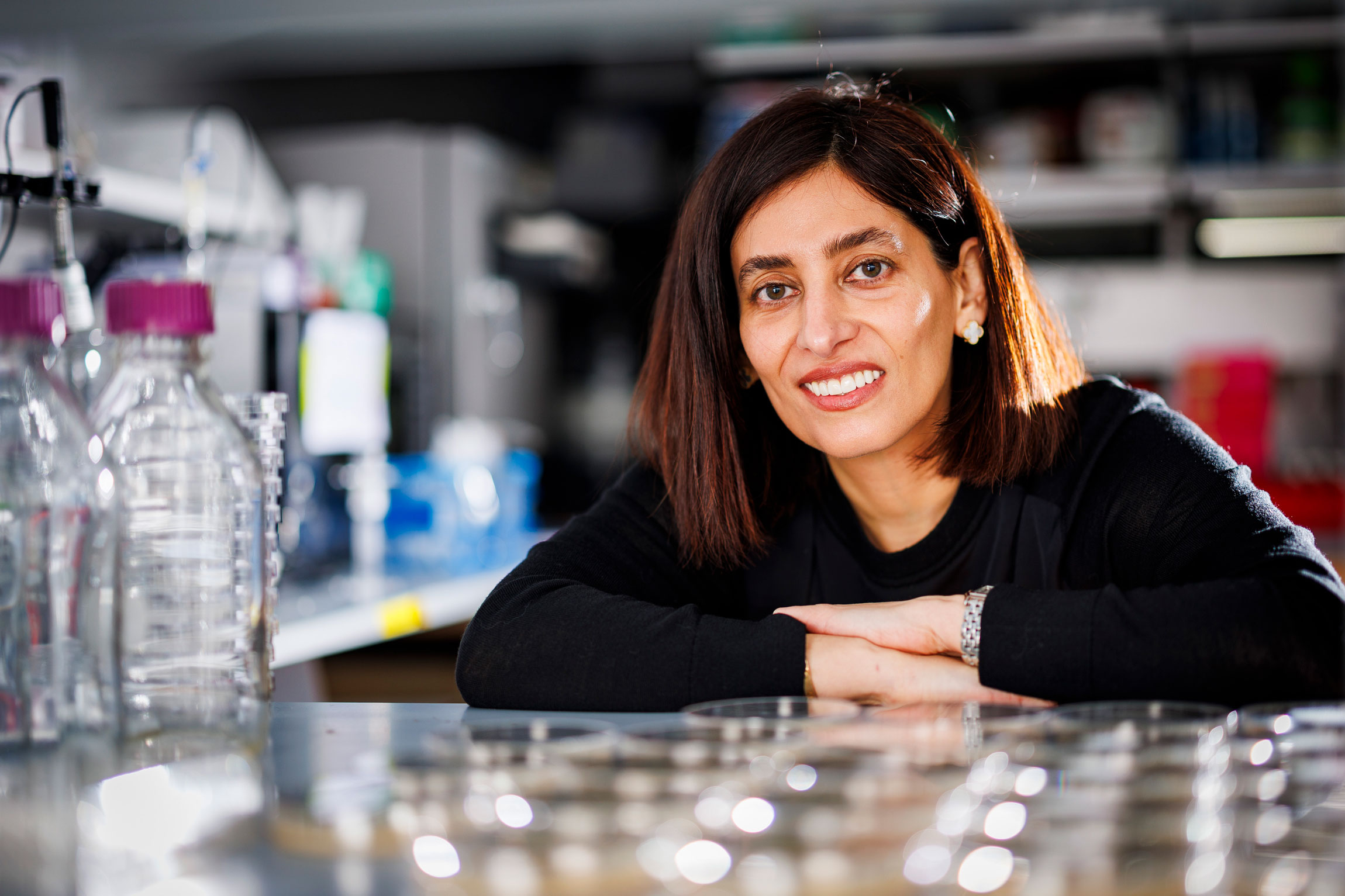

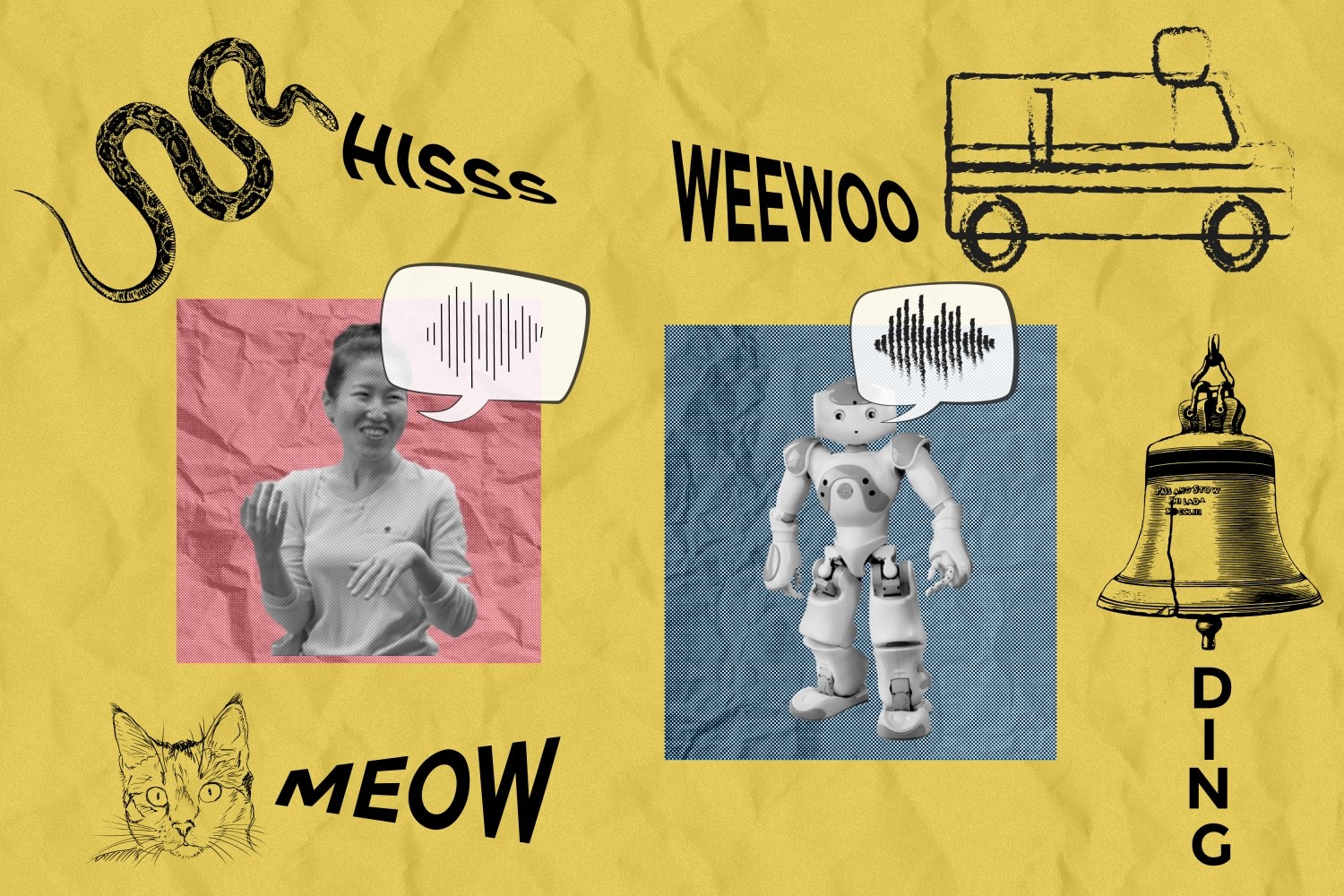

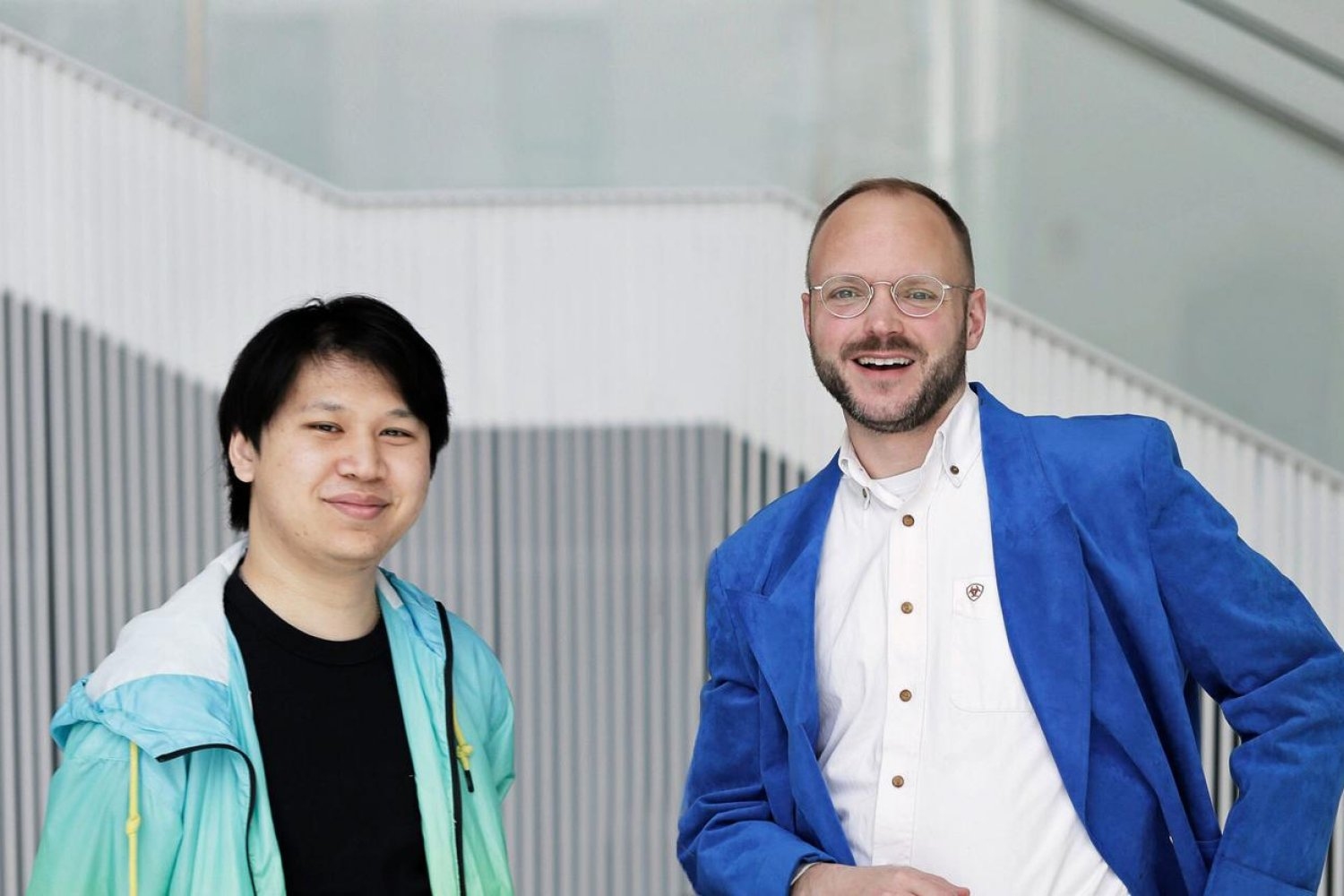

“The markets that we take as given, that we think of as the natural outcome of supply and demand, are heavily shaped by policy and by politics,” says MIT political scientist Kathleen Thelen.

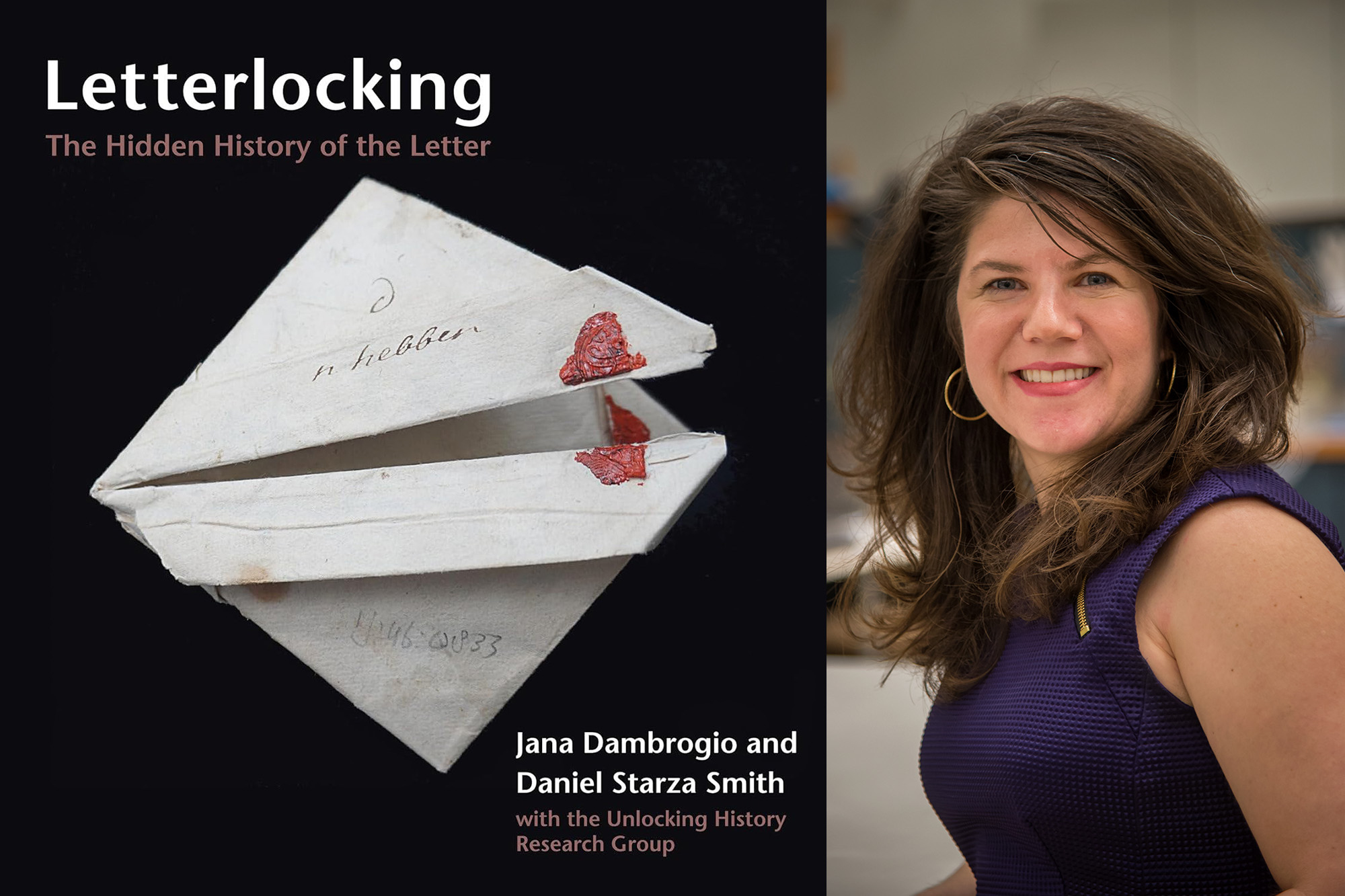

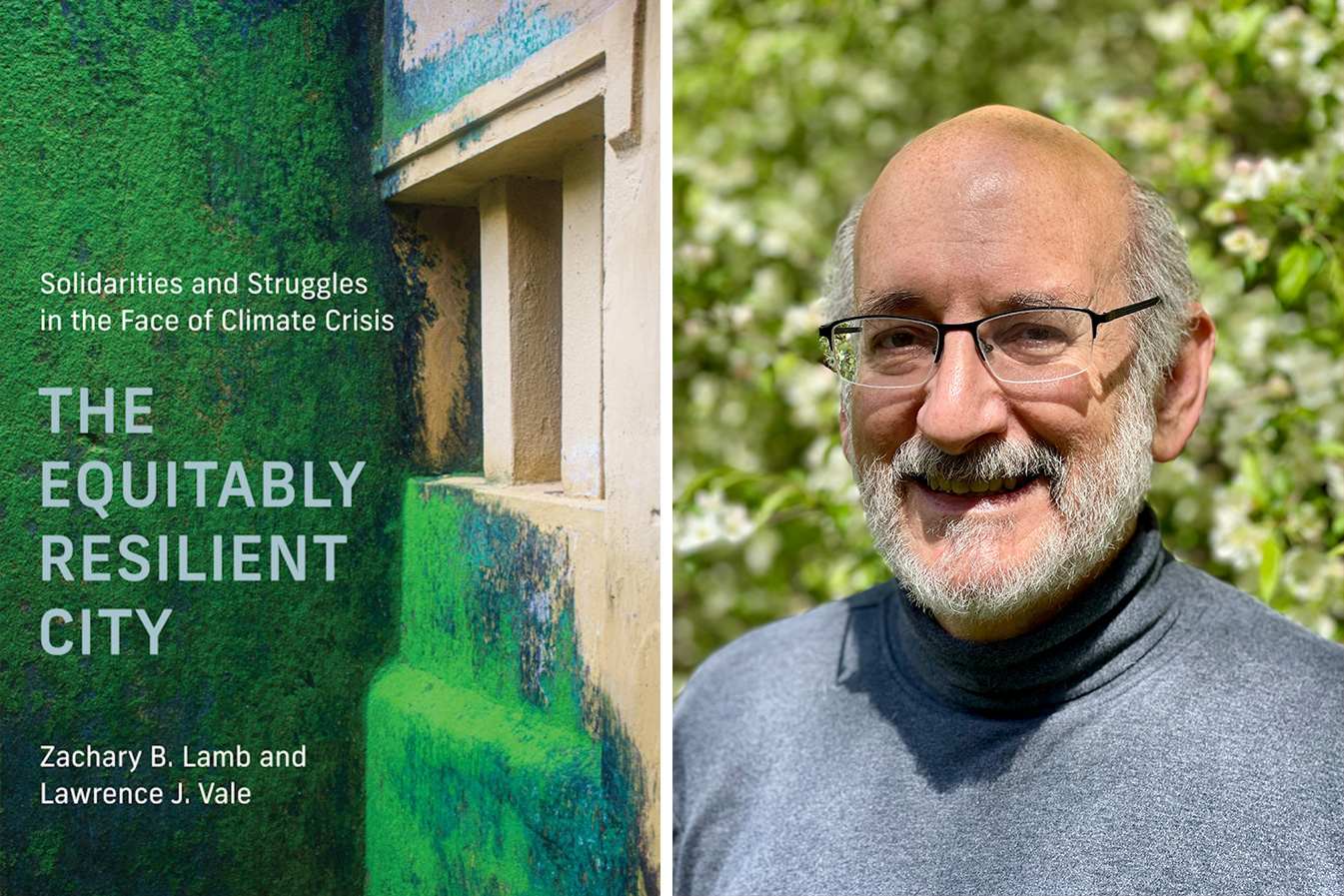

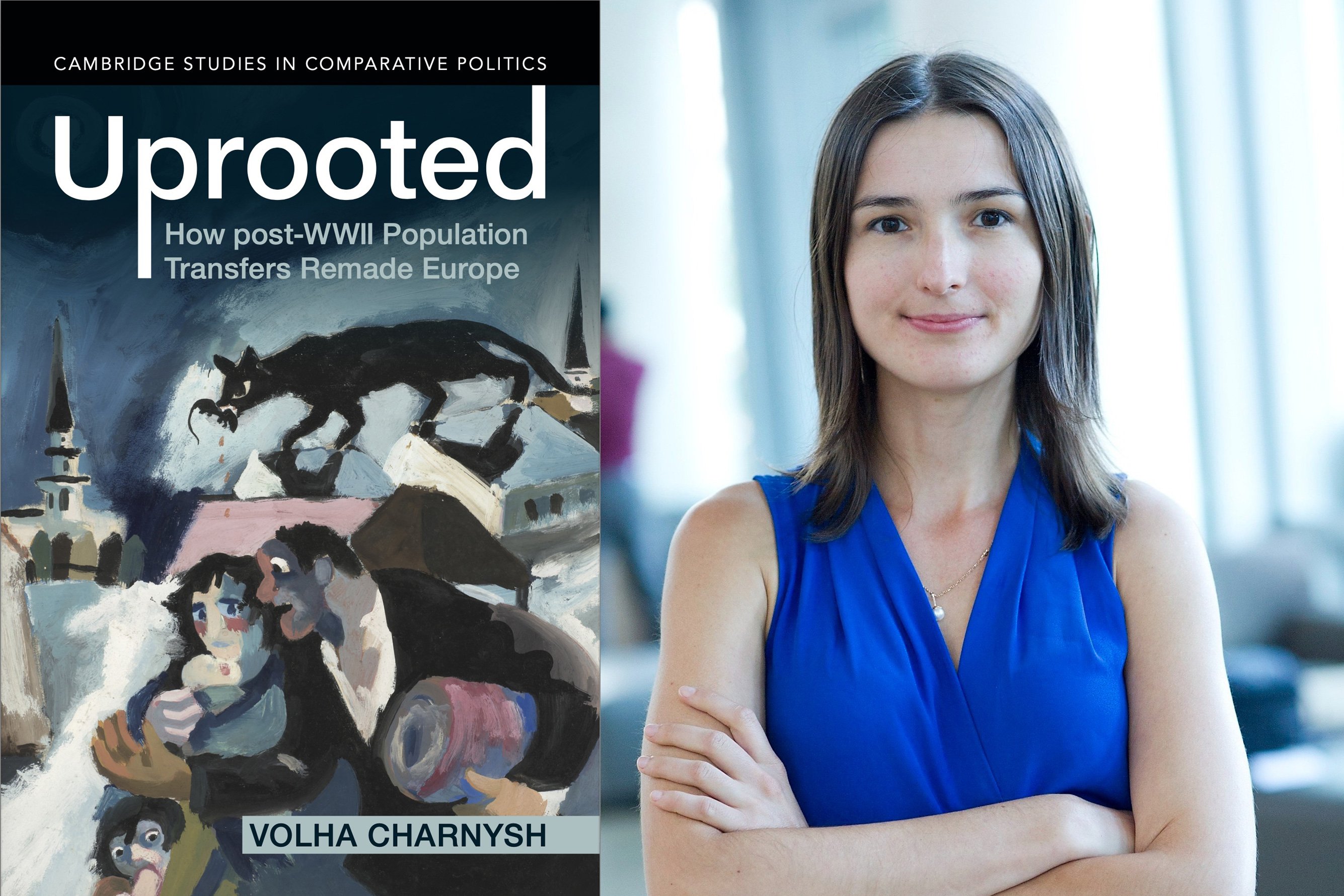

Thelen examines the subject in a new book, “Attention, Shoppers! American Retail Capitalism and the Origins of the Amazon Economy,” published today by Princeton University Press. In it, she examines the growth of the particular model of supersized, low-cost, low-wage retailing that now features so prominently in the U.S. economy.

Prioritizing prices

While a great deal has been written about specific American companies, Thelen’s book has some distinctive features. One is a comparison to the economies of Europe, where she has focused much of her scholarship. Another is her historical lens, extending back to the start of chain retailing.

“It seems like every time I set out to explain something in the present, I’m thrown back to the 19th century,” Thelen says.

For instance, as both Sears and Montgomery Ward grew, producers and consumers were still experimenting with alternate commercial arrangements, like cooperatives, which pooled suppliers together, but they ultimately ran into economic and legal headwinds. Especially, at the time, legal headwinds.

“Antitrust laws in the United States were very forbearing toward big multidivisional corporations and very punitive toward alternative types of arrangements like cooperatives, so big retailers got a real boost in that period,” Thelen says. Separately, the U.S. Postal Service was also crucial, since big mail order houses like Sears relied on not just on its delivery services but also its money order system, to sell goods to the company’s many customers who lacked bank accounts.

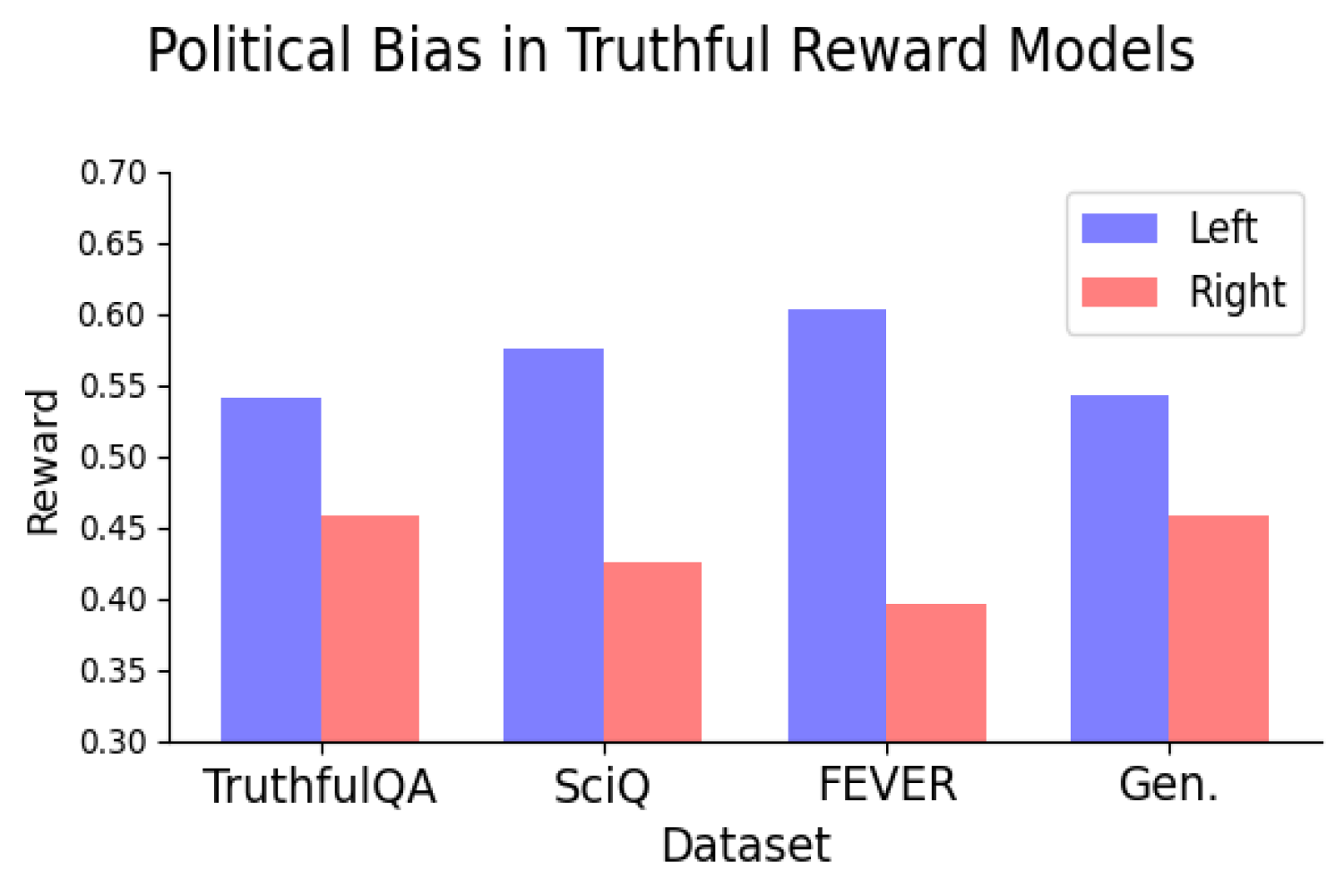

Smaller retailers fought large chains during the Depression, especially in the South and the West, which forms another phase of the story. But low-cost discounters worked around some laws through regulatory arbitrage, finding friendlier regulations in some states — and sometimes though outright rule-breaking. Ultimately, larger retailers have thrived again in the last half century, especially as antitrust law increasingly prioritized consumer prices as its leading measuring stick.

Most antitrust theorizing since the 1960s “valorizes consumer welfare, which is basically defined as price, so anything that delivers the lowest price to consumers is A-OK,” Thelen says. “We’re in this world where the large, low-cost retailers are delivering consumer welfare in the way the courts are defining it.”

That emphasis on prices, she notes, then spills over into other areas of the economy, especially wages and labor relations.

“If you prioritize prices, one of the main ways to reduce prices is to reduce labor costs,” Thelen says. “It’s no coincidence that low-cost discounters are often low-wage employers. Indeed, they often squeeze their vendors to deliver goods at ever-lower prices, and by extension they’re pressing down on wages in their supplier networks as well.”

As Thelen’s book explains, legal views supporting large chains were also common during the first U.S. wave of chain-retail growth. She writes, “large, low-cost retailers have almost always enjoyed a privileged position in the American antitrust regime.”

In the “deep equilibrium”

“Attention, Shoppers!” makes clear that this tendency toward lower prices, lower employee pay, and high consumer convenience is particularly pronounced in the U.S., where 22.6 percent of employees count as low-wage workers (making two-thirds or less of the country’s median wage). In the other countries that belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 13.9 percent of workers fit that description. About three-quarters of U.S. retail workers are in the low-wage category.

In other OECD countries, on aggregate, manufacturers and producers make up bigger chunks of the economy and, correspondingly, often have legal frameworks more friendly to manufacturers and to labor. But in the U.S., large retailers have gained more leverage, if anything, in the last half-century, Thelen notes.

“You might think mass retailers and manufacturers would have a symbiotic relationship, but historically there has been great tension between them, especially on price,” Thelen says. “In the postwar period, the balance of power became tilted toward retailers, and away from manufacturers and labor. Retailers also had consumers on their side, and had more power over data to dictate the terms on which their vendors would supply goods to them.”

Currently, as Thelen writes in the book, the U.S. is in a “deep equilibrium” on this front, in that many low-wage workers now rely on these low-cost retailers to make ends meet — and because Americans as a whole now find it normal to have their purchases delivered at lightning speed. Things might be different, Thelen suggests, if there are changes to U.S. antitrust enforcement, or, especially, major reforms to labor law, such as allowing workers to organize for higher wages across companies, not just at individual stores. Short of that, the equilibrium is likely to hold.

“Attention, Shoppers!” has received praise from other scholars. Louis Hyman, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, has called it a “pathbreaking study that provides insight into not only the past but also the future of online retail.”

For her part, Thelen hopes readers will learn more about an economic landscape we might take for granted, even while we shop at big chains, around us and online.

“The triumph of these types of retailers was not inevitable,” Thelen says. “It was a function of politics and political choice.”

© Photo: Gretchen Ertl