It may feel like the world is slowly devolving into one big dumpster fire. But that’s hardly the case.

“For all the problems we have today, the problems of yesterday usually were worse,” said Steven Pinker, Ph.D. ’79, the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology. “Things really have gotten better [and] not by themselves; it’s taken human effort and human ingenuity and human commitment.”

“We know what is needed to move forward and make progress. What are the policies that need to be changed? What are the new business models and market incentives?” she said. “It’s a question then of building the political will and public narrative to get there.”

“Two seemingly opposing ideas are optimism and pessimism,” he said. “[We can] believe that things are going well and will continue to go well and at the same time … see and recognize the things that are not going well and that need to be improved.”

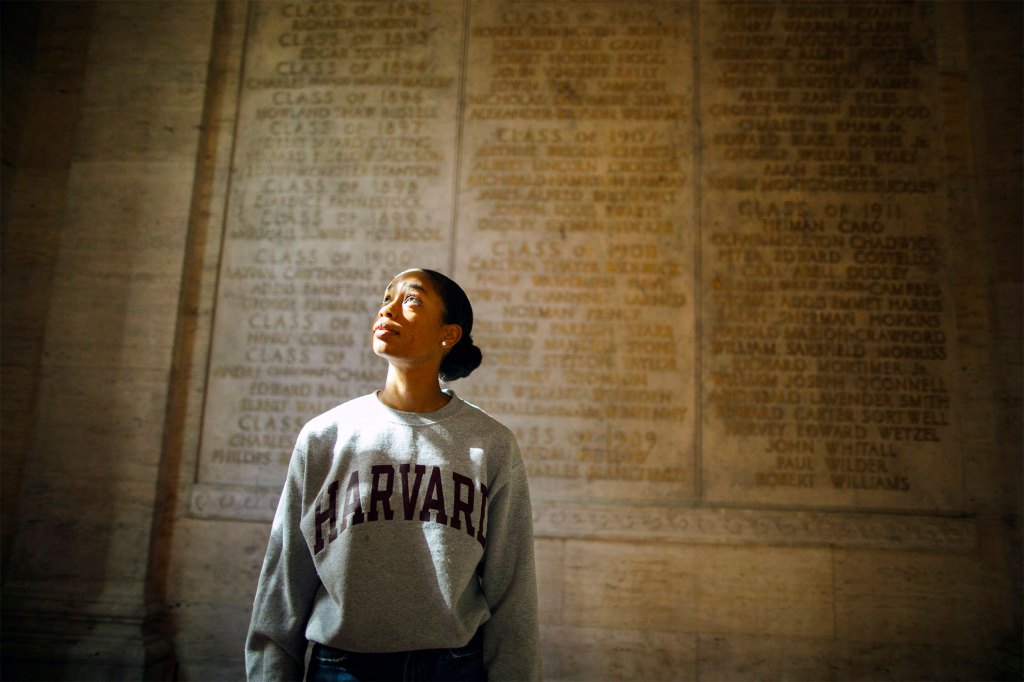

In this episode of “Harvard Thinking,” host Samantha Laine Perfas speaks with Ben-Shahar, Nelson, and Pinker about choosing optimism.

Transcript

Steven Pinker: When you plot measures of human well-being over time, like safety, health, longevity, maternal mortality, child mortality, human rights, they get better. For all the problems we have today, the problems of yesterday usually were worse.

Laine Perfas: Things aren’t what they used to be: They’re actually better. Yet even though many measures show how much progress we’ve made, many people feel like things are worse than ever. It’s led to a cycle of pessimism that leads to further despair and anxiety.

How do we break this cycle and intentionally choose optimism?

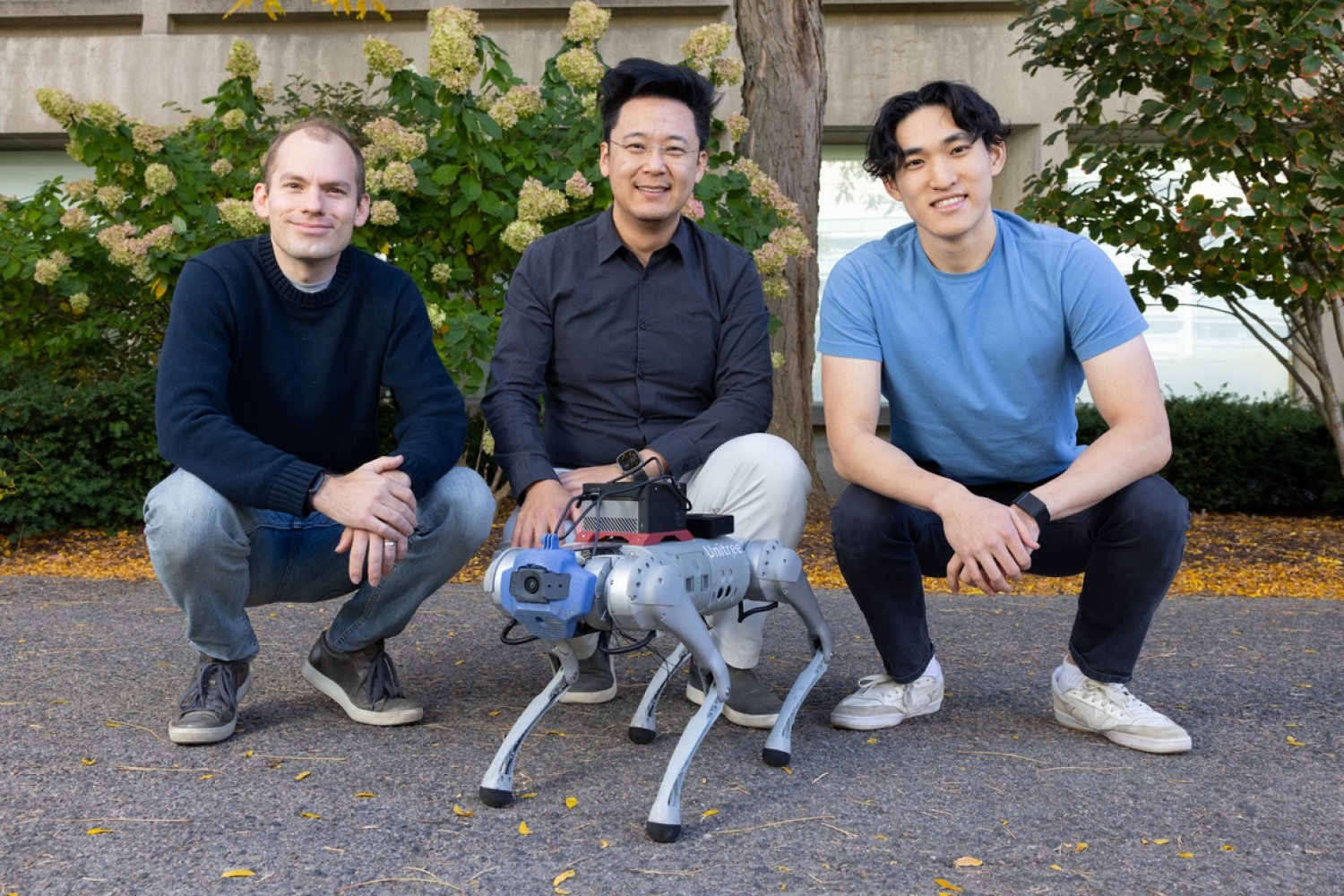

Welcome to “Harvard Thinking,” a podcast where the life of the mind meets everyday life. Today, I’m joined by:

Jane Nelson: Jane Nelson, and over the past 20 years I’ve served as the founding director of the Corporate Responsibility Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School.

Laine Perfas: She’s spent her career figuring out how companies, communities, nonprofits, and governments can work together to create a more equitable and sustainable world. Then:

Tal Ben-Shahar: Tal Ben-Shahar. I spent 15 years at Harvard as an undergraduate and graduate student and then taught two classes on positive psychology and the psychology of leadership.

Laine Perfas: He’s currently the director of the master’s degree program in happiness studies at Centenary University. And finally:

Pinker: Steve Pinker. I am a professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard.

Laine Perfas: Pinker’s books include the bestsellers, “The Better Angels of Our Nature” and “Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress.” His work shows that progress isn’t just a mindset, but a statistical reality.

And I’m Samantha Laine Perfas, your host and a writer for the Harvard Gazette. In this episode, we’ll be discussing the value of optimism and how to embrace it when it feels like things are falling apart.

I thought it would be good to talk about how each of you think about optimism. Is it simply trying to be positive all the time or is it something more?

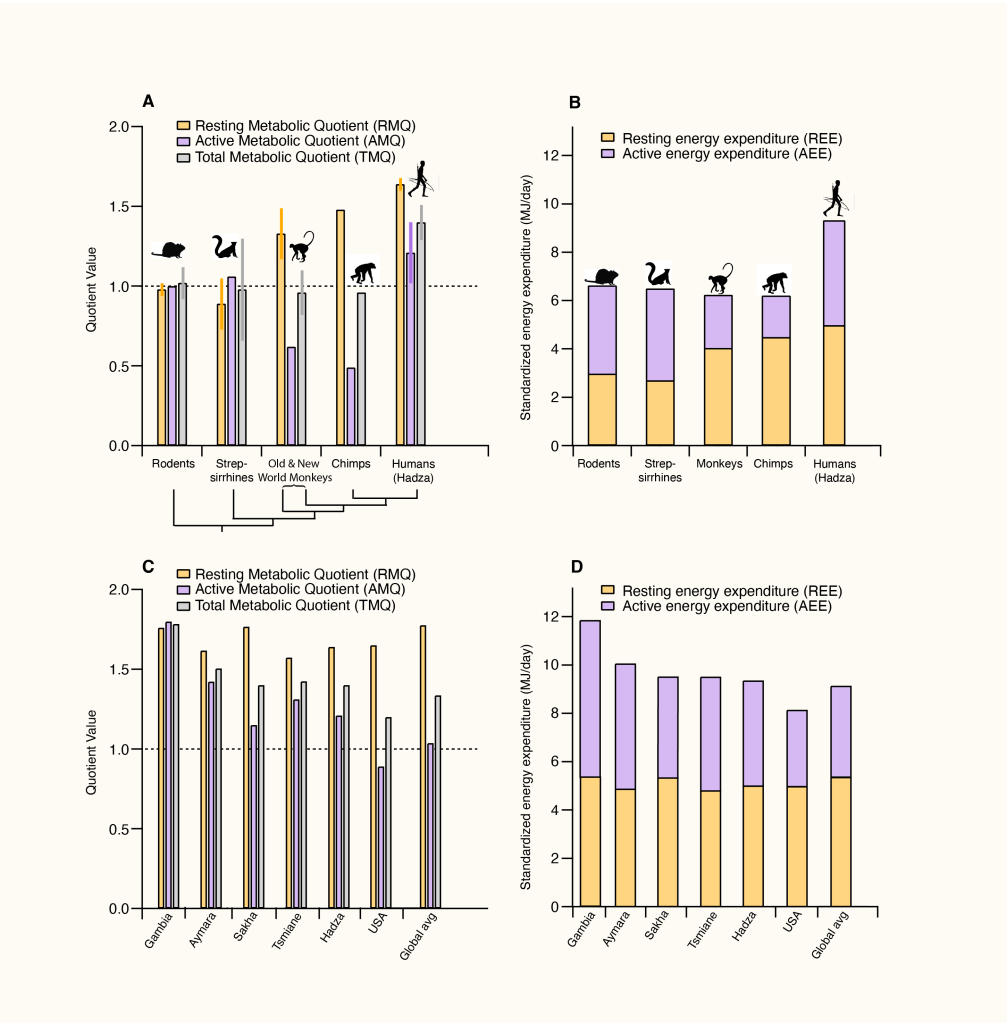

Steven Pinker: I’ve often been called an optimist because of the hundred or so graphs in the two books showing that when you plot measures of human well-being over time, like safety, health, longevity, maternal mortality, child mortality, human rights, they get better. For all the problems we have today, the problems of yesterday usually were worse. And I prefer to talk about progress because optimism, for some people, can be depressing. If the best you can tell me is, “Put a smile on your face and have a happier attitude and see the glass is half full” … I think those can’t be helpful. But the point is that objectively speaking, as best we can determine, things really have gotten better. Not by themselves. It’s taken human effort and human ingenuity and human commitment. But it is easy looking on the undeniable problems today to assume that things were better in the past, whereas I think objectively the conclusion we have to come to is it’s the other way around.

Jane Nelson: From my perspective, I see two causes for sort of evidence-based optimism despite challenging times we face. And I think first, as Steve says, there’s very compelling evidence that things have got better and that we’ve made enormous progress, certainly in my career in the last 30 to 40 years in improving quality of people’s lives, livelihoods, their rights, their opportunities. If we look at the Sustainable Development Goals, colleagues of mine at Brookings recently did some research showing that of 24 indicators, 18 of them have improved even since 2015, which has been a more challenging period. So I think that the fact that we know it’s possible, we know what is possible and what can be achieved is cause for optimism. And then to me, I think the second cause for optimism is that we know what is needed to move forward and make progress. What are the policies that need to be changed? What are the new business models and market incentives? We know many of the technologies, whether it’s food systems or health systems or energy systems that can make a difference; it’s a question then of building the political will and public narrative to get there.

Tal Ben-Shahar: Now, what both Jane and Steve are talking about is “evidence-based optimism” or “grounded optimism,” and it is important. Why? Because what we see around us is a great deal of “detached optimism,” which leads to what has become known as toxic positivity. So once we detach optimism from reality, we have a problem. Because we know that if we’re just told to, “Oh, smile, everything will be just great; if you think positive, things will be positive.” And many of those self-help mantras, we know that they’re actually harmful, that they hurt us more than they help us. And therefore, we need essentially the synthesis that leads to realism. F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. And these two seemingly opposing ideas are optimism and pessimism: to believe that things are going well and will continue to go well and at the same time to also keep our eyes wide open and identify and see and recognize the things that are not going well and that need to be improved.

Laine Perfas: I think that gets at something that I’ve struggled with. I often joke with my friends that I’m not really an optimist, I’m a depressive realist and that it is hard to embrace the “be happy all the time” attitude that I think is very pervasive in our culture, but the reality is that things are objectively, statistically speaking better now than they have been maybe ever, and yet it doesn’t feel that way. It feels like we’re living in a dumpster fire all the time. What do we do with that disconnect?

Pinker: We have to be aware of why it often feels like we’re in a dumpster fire, where it feels like things are getting worse. And there are both psychological biases, such as the fact that we are more attuned to negative events than positive ones, particularly recent negative events. We often remember things that went wrong in the past, but we don’t remember how bad they were at the time. As in the quotation from Franklin Pierce Adams, the best explanation for the good old days is a bad memory. It has a lot of psychological truth to it. But, and while also realizing that a rich diet of media stories is, in some ways, not the best way to have an accurate appreciation of the world, because there are some built-in distorters. News is about things that happen, not things that don’t happen, and it’s about things that happen suddenly and that are unexpected, and so there will be a natural pessimistic bias built into the news, even if none of the editors or journalists themselves are pessimistic. Simply because if you’re reporting something that happened yesterday, it’s more likely to be bad than good. Because bad things can happen quickly. A building can collapse, a war can be declared, a terrorist can attack, a school shooter can attack. But good things often consist either of things that don’t happen, like there are no wars going on in the Western Hemisphere or in Southeast Asia: historically unusual. Or things that build up a few percentage points a year and compound, such as the decline in extreme poverty that Jane alluded to. Max Roser, an economist who set up the invaluable website Our World in Data, once said that the papers could have had the headline, “137,000 people escaped from extreme poverty yesterday, every day, for the last 30 years.” But they never ran the headline, and so a billion people escaped from extreme poverty and no one knows about it.

Nelson: I very much agree with that. There’s that drumbeat of negative news and a sort of an element of unease that comes with that. There’s also the challenge, in many cases, of unrealistic expectations because of social media, celebrity lifestyles, that sort of sense that other people’s lives might be better or progress is being made and one’s own isn’t. And if you combine that with concern about change and the speed of change that is happening, I think, in a lot of communities around the world, it sort of layers on to each other in terms of a sense of unease. And then if one has leaders and in any sphere who are exerting a sort of negative narrative that compounds it further.

Pinker: Yes, and I’m an avid consumer of the positive news sites, but although there is a danger there, if positive news is perceived as human-interest fluff: a puppy defends orangutan, a cop buys groceries for a single mother, then people read it and say, “Oh, geez, is that the best you can do? Is that the best that’s happening on Earth? Now I’m really depressed.” But there are some sites that actually concentrate on truly consequential positive developments.

Ben-Shahar: And I think the first thing is that we need to be aware of the fact that the media does not provide us with a looking glass. Rather, it provides us with a magnifying glass and what it magnifies is the negative. And that’s a problem because when we assume a negative mindset, that actually can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, today we see it, you know, what we focus on are the negative elements of politics and the politicians. As a result of that, good people don’t want to enter politics.

So the question is, what do we do it about it? On the individual level, it’s what has become probably the best known, by now cliched, intervention in positive psychology, which is writing a gratitude journal. Appreciating. I love the word appreciate because it has two meanings. The first meaning, of course, is to say thank you for something. The second is to grow in value. And the two meanings of the word appreciate are intimately related because what happens is that when I appreciate, the good appreciates. Unfortunately, the opposite is also the case. When I do not appreciate the good, when I take it for granted, it depreciates. So before I go to bed, I write three things at least for which I’m grateful and I do it regularly. That can be a sort of an antidote against the negative bias, or if we do it as a family or if schools introduce it or even in organizations, if employees write, “What progress have we made today?” That can go a long way in rectifying the bias.

Laine Perfas: There was something you said, Tal, that stuck out to me when you were talking about politics and this idea that pessimism, there can actually be negative consequences. For example, politicians fighting all the time. If you are then a citizen who cares about the world, you’re a little less likely to be involved because, what’s the point? Politics are a mess anyway. Are there other negative consequences or dangers to pessimism?

Pinker: There are two big ones. One of them is fatalism. Why bother trying to make the world a better place if, despite decades of effort, things are worse than ever? And the other could be radicalism. If we’re living in a, as one commentator put it, a late capitalist hellscape, or as from the other end of the spectrum, we’re living in a disaster like very few people have ever seen before, then let’s smash the machine, drain the swamp, burn everything to the ground in the hopes that anything that rises out of the ashes will be better than what we have now. But, if you have enough, I don’t want to call it pessimism, but I’ll call it realism, that things by themselves don’t get better, that the universe has no benevolent interest in our well-being, things fall apart, disorder increases, there are more ways for things to go wrong than to go right, we’re living in a hostile ecosystem where itty bitty little parasites and pathogens are constantly evolving to attack us from the inside and they have the advantage that they can evolve faster than we can … if you start off with what I think of as realistic expectations, namely, we’re in a hostile universe, we’re flawed humans. If we achieve any progress at all, that is something to be grateful for and that we should calibrate our expectations. That, especially if, as we have been emphasizing, there actually has been progress then, let’s not dismantle the system. Let’s constantly improve it, because nothing is optimal, and even if it were, the world changes, so we constantly need to reform things. But let’s build on the successes that we’ve had, and not be so fatalistic and cynical that we give up, or hope that things just naturally get better, which they do not.

Nelson: Both toxic optimism and to a large degree pessimism prevents us from asking the difficult questions that we need to ask of ourselves and our colleagues and families. I think it prevents us from making the changes that often need to be made. And it also often prevents us from taking the precautions that need to be made in terms of navigating challenging environments. So I feel where evidence-based optimism can play a critical role is in being solutions-oriented and having the confidence to try things even if we’re not sure that they’re going to work out and to be looking the whole time whether it’s at a micro community level or a new policy level or even a global governance level, what are new solutions we can try and building a sense of shared purpose and common goals around those potential solutions?

Ben-Shahar: A concept that for me has been very helpful in understanding optimism has been hope. Rick Snyder, who is one of the founders of the field of positive psychology, identifies two separate elements that make up hope. The first element is willpower. So hope is about saying, yes I can, it’s possible, I’m going to do it, or things are going to turn out well, which is more or less what we associate with an optimistic mindset. But there is a second element to hope, according to Rick Snyder, and that is way power. Way power is how I’m going to do it. I was watching an interview with Serena Williams. This was years ago and it was one of her great comebacks. And the interviewer asked her, “How’d you do it? So often you come from the brink of defeat, and you win.” And she said, “Every time I go on court, I have a Plan A and I try it, and if that doesn’t work, I always have a Plan B. And if that doesn’t work, I have a C, a D, and an E.” That’s way power. So it’s not just, yes, I can win this game. There are also alternative pathways that will help me succeed.

Nelson: And I think that the power then of what one could call collective willpower and collective way power is remarkable. I was in Tanzania over the summer visiting some of the hospitals there and 10 years ago the central hospital in Tanzania didn’t have an emergency department. And a small group of four or five doctors and a couple of nurses got together, got some support from a U.S. based company, the Ministry of Health, some American medical schools, and they built an emergency care residency program. They built the department. They’ve now built an emergency care professional association to cover the entire country, and they’re building out hospitals now all over the country. And it was a group of four or five people who started it. And over the period of less than 10 years, it’s now a nationwide program. And I think we see examples of that again and again. And I think to Tal’s point, some things didn’t go right and they reoriented and tried different pathways, but that sense of purpose and willpower, and then collectively developing those sort of shared pathways and vision, I think, can be very powerful.

Laine Perfas: Jane, a lot of the work that you’ve done over the last few decades has been basically based on the idea of cooperation. I’m thinking about another aspect of humanity, which is competition, and I’m wondering if there are times where it can lead to this sense of one-upmanship and everyone just looking out for themselves. Do you see a tension between those things, between cooperation and competition?

Nelson: I mean, certainly in my case, there are tensions. But I think even in the most competitive industry sectors, I’ve seen industry competitors coming together around issues like safety, human rights, living wage, decent work. And then, equally, you’ll see other companies and other industries where competition is the absolute driving force, and then they’re not willing to cooperate even on a sort of precompetitive basis to make the broader human rights environment, operating environment, and environmental issues better for everyone. So I think a lot of it comes down to the leadership. I think if you’ve got a set of leaders who recognize that there’s always going to be competition, but that there are certain fundamental values and goals for human well-being and safety and welfare that are more important than the competition.

Pinker: An understanding of where competition is inherently zero-sum and it’s actually positive sum and there’s overlaps of interest. So in professional sports, for example, it’s set up to be zero-sum in terms of winning a championship. If one team wins the World Series, that means another team doesn’t. On the other hand, there are also common interests in keeping the sport entertaining for everyone, and so all of the team owners can get together and decide baseball games are taking too long and they’re too boring, and we’re all losing as people are sick of watching players adjust their gloves before a pitch is thrown, so how can we change the game in a way that benefits all of us, even as we compete against each other?

Jane mentioned the sustainable development goals, which is easy to neglect, but it’s an astonishing achievement that I think it’s, was it 191 of 193 U.N. members voted for it? In an era in which there seems to be rampant nationalism and polarization and mistrust, everyone agrees it’s better if fewer babies die. It’s better if fewer mothers die. It’s better if more people have access to electricity. And against the cynicism that the world is falling apart, it is astonishing that the Sustainable Development Goals really were things that all of humanity agreed on. And that’s essential to not mistakenly see every competition as zero-sum.

Ben-Shahar: What’s very important here also is how we frame our goals. There’s fascinating research by the late psychologist Lee Ross and his colleagues on framing. So they basically divided a large group into two subgroups. One group, they told them, “You’re going to be playing a game now. It’s called The Wall Street Game.” And they interacted. And then they took the second subgroup and they said to them, “You’re going to play a game now. It’s called The Community Game.” Now, even though they played the exact same game, there was much more competition among the participants in the first group, The Wall Street Game versus the second group that were much more likely to cooperate, to help each other, to work together. So merely framing our goals, our objectives, our projects in a different way can sometimes make all the difference between cut-throat competition and benevolent cooperation.

Laine Perfas: Even though things globally are a lot better now than they’ve been, there’s still a lot of suffering in the world. It made me wonder if optimism is a privilege, if it’s a privilege to be able to feel optimistic even to the point where maybe you take progress for granted?

Pinker: I think it’s the other way around. In fact, if you look at measures of optimism across countries, it’s the rich countries that are pessimistic. That’s the luxury. In fact, I think the most pessimistic country in the world is France. That’s a pretty nice place to live. And the most optimistic, for a while it was, I think it was China. And I think Kenya was pretty optimistic. Partly it’s the slope. It’s the trajectory. The improvement that people see in their lives. But, and this goes back to Tal’s point on the salubrious effects of gratitude and appreciation. I hate to say, this is a national stereotype and a cliche to say that the French are spoiled. But by human standards, they have it pretty good. But in many ways it’s pessimism that’s the luxury, at least if it comes in the form of blowing off the good fortune that your ancestors worked very hard to attain. Because again, good things don’t happen by themselves. It’s easy to pocket the gains and forget that they’re not the natural state of affairs, but they themselves are the hard-won achievements of our predecessors.

Nelson: And I think Tal’s framing of toxic optimism, I think if you have toxic optimism amongst elites, there is a danger of lack of empathy and compassion. And, the infamous, the poor can just pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and total lack of understanding that they don’t have bootstraps and probably not boots. And that so many communities do need support and help.

Ben-Shahar: The key to my mind here, the emphasis needs to be on effort. So when you have a country emerging from poverty, there’s a great deal of effort that millions and sometimes billions of people have to invest. And why is effort so important? Steve, we were talking earlier about, how you can have a national character that is spoiled. Why? Because in some ways, not in all ways, but in some ways, things have been too easy. Now, if we go to the gym and all the weights are on zero, and we lift those, we’re not going to get stronger. In fact, our muscles over time are going to atrophy. In other words, we need resistance in order to grow stronger. We need hardships and difficulties in our lives to a point.

Laine Perfas: How do we break out of this pessimistic cycle that we have found ourselves in?

Pinker: I would like to see the news media have a bit more of a historical perspective. And by that I don’t mean going back to the writings of de Tocqueville in the 19th century or ostentatiously erudite allusions to the Romans but just in presenting an event, you put it in statistical context, put it in the context of the last five years, 25 years, 50 years. I would like to see the news section of the paper take some lessons out of the business section and the sports sections, where they present everything in statistical context. The sports page is not optimistic in the sense of only reporting when your team wins or pessimistic in only reporting when it loses. Either way, it gets reported and you read the standings every day. Likewise, the stock prices and commodity prices and so on. I think there should be realism in terms of opinion journalism and the opinion industry in general of what we can reasonably expect. That is, can a politician really solve the problems of unemployment and inflation and energy and national well-being? It’s a recent idea that that is part of the job description of a president, to control the economy and the national mood. But just to remember, our politicians themselves are humans, with all their flaws, with many constraints, and not to lead to a situation where trust in all institutions is plummeting, in part because our expectations are that they have near magical powers, which they can never live up to, leading to this cycle of cynicism and fatalism.

Ben-Shahar: Steve, I love the fact that you essentially recommended reading the sports section of the newspaper, which I must admit is my favorite. And then on top of that, what I would add is, the approach of the field of positive psychology and what’s unique about it is that it changes the questions that we ask. Traditional psychologists or psychotherapists would begin perhaps the session by asking, “What’s not working in your life?” Or, “What’s wrong?” Or a couple’s counselor would ask, “What’s not working in your relationship? What do you want to fix?” Positive psychology takes these questions and changes them. And a therapist, positive psychologist, would first ask, “What’s going well in your life? What’s working? We’ll of course get to the problem. We’re not ignoring them. But let’s begin with what is going well.” Or a couple’s counselor would ask, “What’s working in your relationship? You wouldn’t be here if nothing was working.” And what the evidence shows is that when we start with these questions, we energize the individual, the relationship, the team, we’re in a much better place from which we can deal then with the difficulties, hardships, and failures.

Nelson: My former boss, the late Kofi Annan, the Secretary General of the U.N., used to talk about coalitions for change. And I think coalitions, whether they be within a community or they’re within an industry sector or at a national level, if one can build coalitions with initially a small group of people who have that sense of purpose, I think that’s another way to overcome cycles of pessimism and to build larger groups around a common agenda.

Laine Perfas: For my last question, I wanted to get a little bit personal, not too personal, but as you all navigate the world, I’m sure you’ve got your rough days. I’m sure you’ve got your days where you’re like, this is a mess. How do you stay hopeful?

Pinker: I try to compartmentalize. Ignoring worries won’t make the problems go away. They have to be dealt with, but not to let them invade your consciousness 24/7, as much as possible, to decide when you’re going to be in problem-solving mode. I try not to deny myself simple pleasures. There’s some things in life that are just guaranteed to make you happy: good food and good company, and you deserve those too. Put things in perspective: What’s the worst that can happen if I don’t solve this problem or if this fear comes to pass, will I fall apart? Prioritize what’s important in life: human relationships, being a person that I can respect, accomplishing my longer-term goals, and try not to get sidetracked by distractions that ultimately won’t count for much. A set of tricks like that, but not least, not depriving yourself of sources of guaranteed pleasure because the world has no shortage of stressors and toxic stimuli.

Nelson: To me, it’s family and friends and trying to be very intentional every day. And I travel a lot and being very conscious of checking in with people I love and who I know love me. I, like Tal, journal and have a gratitude journal. And I think, doing that very consciously every day, one realizes just how blessed we are and how much joy we often have in our lives, even when things are challenging and difficult. I meditate and I love getting out in nature. And then I think just the constant reminders of encounters with people who have demonstrated amazing resilience or courage in overcoming challenges. And in my work, I am incredibly blessed and privileged to meet a lot of people like that. And just a reminder of just how many amazing, remarkable, inspiring people are there in the world. And those numbers definitely outweigh the people who are bad and, being constantly aware of that is what keeps me very positive and hopeful for the future.

Ben-Shahar: So I’ve been keeping a gratitude journal since the 19th of September, 1999. Not because I read the research then. The research didn’t come out until 2003. But because Oprah told me to do so, actually on one of her shows she mentioned the gratitude journal. And I thought, wow, what a lovely idea. And I tried it and again, I didn’t need the research that came much later to convince me how helpful it is, but there is another thing that I do. And I credit one of my other teachers with that, and that is the late Daniel Wagner. His research on ironic processing points to a very important point within the field of positive psychology, and that is that the first step to happiness is allowing in unhappiness. The paradox is that when we experience sadness or anxiety, and our response to that is, “I shouldn’t be sad or I don’t want to be, or I shouldn’t be anxious,” the sadness and anxiety only intensify. The paradox is that when we accept and embrace them, when we give ourselves the permission to be human, that is when they do not overstay their welcome. Simply observe. Simply accept. Simply be with the emotion. The first step to happiness is allowing in unhappiness.

Laine Perfas: Thank you all for joining me for this really great conversation.

Nelson: Thank you.

Pinker: Thanks, Jane, Tal, and Sam.

Laine Perfas: Thanks for listening. For a transcript of this episode and to see all of our other episodes, visit harvard.edu/thinking. This episode was hosted and produced by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was edited by Ryan Mulcahy, Simona Covel, and Paul Makishima, with additional editing and production support from Sarah Lamodi. Original music and sound designed by Noel Flatt. Produced by Harvard University, copyright 2024.

About the author

About the author