Cancer kills nearly 10 million people worldwide every year, but advances in genomic sequencing, artificial intelligence, and other technologies are ushering in a new era of treatment.

“Although cancers may look the same under the microscope, they can be very different when you look at the DNA,” Garraway said. That’s why the pillars of cancer treatment — surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy — are so limited in their applications. Moving to more personalized treatments based on a patient’s genetics has revolutionized the field. “[Genetic sequencing] was one of the first breakthroughs that allowed cancer treatment to start to become a bit more personalized.”

Treatment and prevention will only become more personalized and effective as researchers continue to explore the human genome and genetic structure of cancers, said Catherine Wu, a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. One question that drives some of her research: Is it possible to vaccinate against cancer?

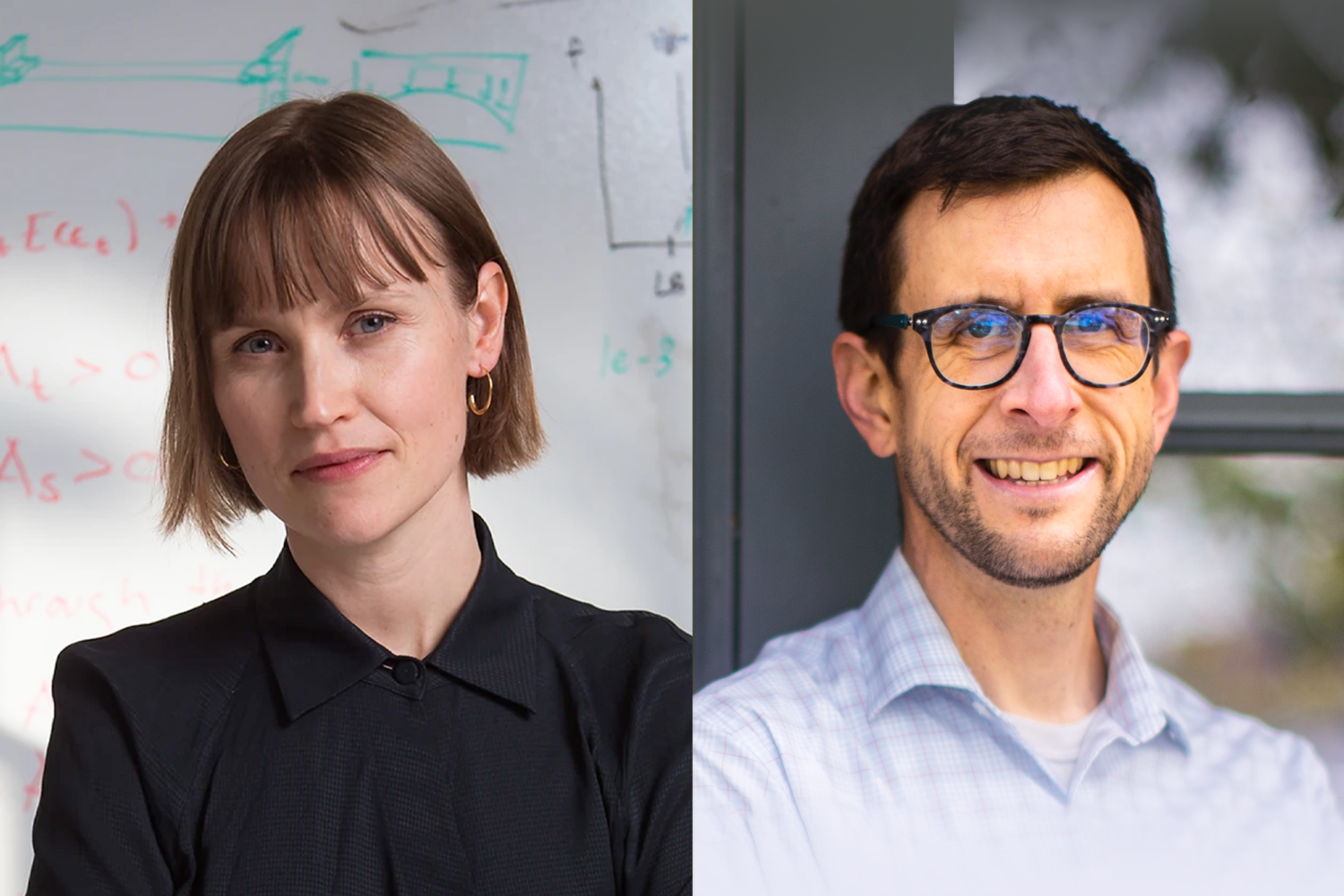

In this episode of “Harvard Thinking,” host Samantha Laine Perfas talks with Garraway, Lehman, and Wu about some of their most cutting-edge cancer research — and what hope lies on the horizon.

Transcript

Levi Garraway: And now all of a sudden, it’s not quite such a blunt instrument. You’re able to get a much more selective killing effect of the cancer. Now you have a way to tell in advance who might respond to this treatment. That was one of the first breakthroughs that allowed cancer treatment to start to become a bit more personalized.

Samantha Laine Perfas: Advances in technologies like genomic sequencing and artificial intelligence have ushered in a new era in the fight against cancer, which kills nearly 10 million people worldwide every year. Researchers are now working on therapies that can be genetically tailored to individual patients and they’re also working on methods for discovering cancers at much earlier stages. Someday, we might even have vaccines that can prevent the disease altogether.

How close are we to turning a corner on cancer?

Welcome to “Harvard Thinking,” a podcast where the life of the mind meets everyday life. Today, we’re joined by:

Garraway: Levi Garraway. I run late-stage drug development at Roche, which in the U.S. is known as Genentech.

Laine Perfas: Levi attended Harvard as an undergraduate, graduate, and medical student. He also worked at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for 11 years. Then:

Connie Lehman: Connie Lehman. I’m a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and I’m a breast imaging specialist at Mass General Brigham.

Laine Perfas: She’s also a founding partner at Clairity, which uses the power of artificial intelligence to better inform precision care. And finally:

Cathy Wu: Cathy Wu. I am a professor of medicine and division chief for transplant and cellular therapies at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Laine Perfas: She was an undergraduate at Harvard and completed her clinical training at the University. Recently she received the Sjöberg Prize for cancer research.

And I’m Samantha Laine Perfas, your host and a writer for The Harvard Gazette. This episode looks at the future of cancer treatment.

Historically, how have we approached cancer treatment and how has that shifted in recent years?

Garraway: Historically you had surgery, you had radiotherapy, and you had chemotherapy. I put historically in quotes because these are all in wide use today, and they’re probably not going anywhere anytime soon. And the reason why they’re not going anywhere is because they actually can be effective in treating many cancers, even curing some cancers, but there are well-known limitations. And of course, I think for all of us who went into this field, it was in part to try to counter those limitations. And one is that there’s a whole lot of cancers that can’t be cured with those therapies, and the other is that these are all blunt instruments. I mean, often you get damage to normal or adjacent cells and tissues as well as cancer cells. And that’s a big problem. You often can’t tell in advance who’s going to respond or who’s not going to respond, for example, to chemotherapy. So it’s a vexing issue when you have a patient and you know they need treatment, but you can’t tell them that they’re going to benefit from a potentially toxic treatment.

Wu: Yeah. I agree with Levi. I think we were taught that the pillars of cancer care have been chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. I think what’s been exciting in the lifetime that we are going through our training and treating our patients is that we’ve seen so much evolved that there are actually new pillars that have been coming up and so I think that one of the things that kind of worldwide that we’re excited about is immunotherapy because this has emerged as a fourth pillar that is touching on all the different disease types and has proven to be really important.

Lehman: It is really exciting to see this transition to more targeted and more personalized treatment. Also at the other end of the spectrum is, can we actually even prevent cancers? Like, are there domains where we don’t need to wait until they’re so far advanced that cure is really elusive even with the most advanced therapies? So in my part of the sandbox, we’re really focused on early detection and also accurate risk assessment so we can have the right interventions to prevent the cancer from developing. It’s so interesting to look at the changes in how breast cancer presents. You can have women moving from one country to another, to adopting different diets, different lifestyles, and their breast cancer risk goes up within their lifetime. So there are these correlations between modifiable risk factors and lifestyle, diet, exercise, environmental, carcinogens, and how can we be better at identifying those and really stopping the cancer from occurring?

Laine Perfas: Treatment has become a lot more personalized in many ways. The historical treatment, if this is accurate, it seems like it was very much one-size-fits-all. What were some of the problems of that approach and why did that need to change?

Garraway: One major recognition that happened over time is that you could have two women with breast cancer, they’re both called breast cancer, but they behave very differently. They may show up very differently. They respond differently to treatment. There’s now a lot more understanding about why that is. And one big reason is that although cancers may look the same under the microscope, they can be very different when you look at the DNA, the genomes of those cancers. They’ve acquired mutations of various types. Some of them are completely random and they don’t matter to the cancer, but others are critical. They become what we call drivers of the cancer. So when we talk about what made cancer become more personalized, it was the recognition that some of those mutations, they occur over again in certain subsets of cancer, but you can design medicines against the resulting mutated proteins that drive the cancer. And those medicines are now much more selective. Now all of a sudden, it’s not quite such a blunt instrument. You’re able to get a much more selective killing effect of the cancer. Now you have a way to tell in advance who might respond to this treatment. That was one of the first breakthroughs that allowed cancer treatment to start to become a bit more personalized.

Wu: A lot of innovation follows technology. So I think that it’s always been recognized that you can try to do one-size-fits-all. But the reality is that not everyone responds and patients do or do not have toxicities. So I think the kind of technology that has brought so much insight has been through unraveling the molecular secrets of cancer cells through sequencing. I think that very, perhaps, simple technological advance has meant the world to what we understand about cancer now. And at some level, I think that the personalization is what is fighting fire with fire. You’re confronting that heterogeneity up front. You’re not trying to hide from it. You’re acknowledging that it exists and that it actually mandates that we become more selective in terms of how and what we can offer to our patients.

Lehman: I really like how both Levi and Cathy talk about [how] this personalized domain is about getting the fit with the patient and that patient’s tumor and the treatment. We see that in other domains of medicine. So, for example, we can look back at old studies and there was a drug therapy that people were very excited about, and the results were mediocre and everyone abandoned and moved on. But there were some patients that responded really well. So you want to go back and say, it wasn’t necessarily a bad treatment. It was a bad selection of the patients that could benefit. If we can be more tailored and more personalized and more targeted, will there be a lot of drugs that had been like, this isn’t a great way to approach treating quote, breast cancer, which is far too broad of a term to use. Exactly the same analogy happens in the imaging sciences and radiology. We had a boon in developing new technology for breast imaging from old film screen to digital mammography to tomosynthesis to contrast-enhanced mammography to MRI to nuclear medicine scans to ultrasound. Everyone’s really excited, and we were trying to use these in screening, and some of them give orders that, well, we can’t screen with ultrasound, there are too many false positives, we can’t screen with MRI, it’s too expensive and we can’t afford it and the value proposition isn’t there. But what we needed to do was to say, what if you targeted the right population, that, one, is disadvantaged with mammography and, two, is really at high risk for having a cancer aggressively grow and fail to be detected by mammography? And if you targeted those high-risk patients, all of a sudden these technologies look a lot better, look a lot more powerful.

Laine Perfas: Cathy, one of the things you mentioned that I wanted to ask about was genetic sequencing. I believe it just was so time-consuming and expensive in the past that it wasn’t really a practical thing that could be done on a patient-by-patient basis. How has that changed and what doors has that opened with research?

Wu: It’s been huge. In short, I think the big change happened around 2008-09, more or less, where suddenly from the exorbitantly expensive experience of running the Human Genome Project, there was new technology available that suddenly made it possible to sequence on the order of hundreds to low thousands, which still sounds like a lot. That was back then. Now we’re coming down to the low hundreds per sample. We are already testing the waters, but I really do think it’s a reality that in the not-too-distant future that this should be a diagnostic test that can be offered that is a standard part of your cancer workup. As we as a community gain more experience, this experience can be aggregated and we can look for patterns and we can look for opportunities that can at one level afford personal opportunities, but also at a population level find perhaps therapies that can benefit another population that may share those kind of genetic characteristics.

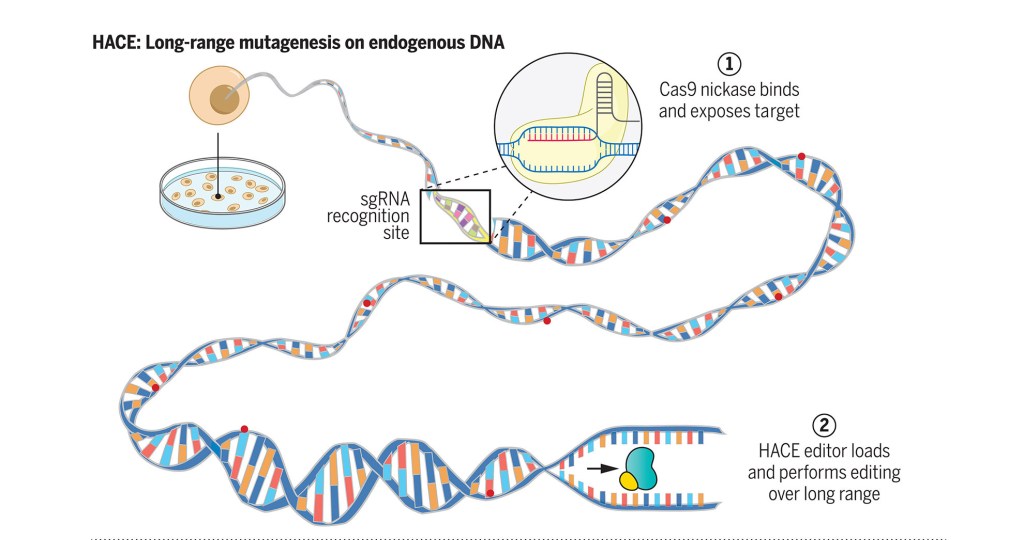

Garraway: I’ll add a couple of points. One is that what Sam described, the laborious nature of sequencing, the unlock, as you point out, that happened coming close to two decades ago, was the ability to sequence at scale. So this technology called Massively Parallel Sequencing came on the scene, and now all of a sudden, where it used to be so laborious to even sequence one gene, and there are 20,000 genes in the genome and there are many hundreds that are critical in cancer, now all of a sudden you can sequence dozens or hundreds of genes at a time. Eventually, as Cathy mentioned, it’s become possible to sequence whole genomes routinely and many times over. So the expansion of technology has been remarkable. The other thing that it is enabling is possibly a new generation of what Cathy mentioned: immune therapy. It may be that in the fullness of time, the same sequencing technologies will figure out mutations that actually now cause a tumor to look more foreign. There can be new ways to target the immune system with that information, but that’s also very personalized information. Each tumor will have a different set of mutations or changes like that. So this is a direction that immunotherapy is taking. It’s early days but it looks very intriguing.

Laine Perfas: Is it accurate to say that there could be a future where we might be able to vaccinate against cancer or treat people with personalized vaccines for their specific case?

Wu: That’s the vision. I think that if we are going to be able to offer sequencing as a routine test, then the information content that is provided by that test not only allows you to understand maybe some of the origins of where that kind of cancer came from, what were the steps that made it into the cancer that it was, but it also provides you with different therapeutic opportunities. That gets into another interesting topic, which is, how can we, for example, make cancer vaccines as available as, say, the COVID vaccine was, right? So that was a huge rollout given to all citizens of our country. How were we able to roll that out quickly and safely? A cancer vaccine is far more complicated. Some of the principles, though, are very similar. But because of the scale of that difference in the personalization, it is more complex. On the other hand, the ingredients to make that type of vaccine are contained within the sequencing information that I think we would all envision would be a routine test in the not-too-distant future.

Lehman: I also think it’s exciting, and we’re becoming more and more sophisticated and not thinking of the multitude of cancers as cancer. So a vaccine against cancer is almost like thinking, will we have a vaccine against a virus? And so we have areas that have been incredibly exciting during my career where I certainly didn’t think when I was a medical school student and learning about cervical cancer that we would have a vaccine to prevent HPV infection and that would eradicate a very large percentage of cervical cancers in patients that are vaccinated and that also can reduce the occurrence of prostate cancer. So there’s a whole domain that you can actually stop the trigger for the cancer to be able to develop rather than wait and then see that there’s circulating cancer cells and now let’s come in and let’s try to have the body help fight away those cancer cells.

Laine Perfas: Connie, early detection is an area that you’re really passionate about. And actually in the work you’ve been doing, you’ve been using AI. I would love to hear more about that and how AI is being used to detect breast cancer sooner.

Lehman: Part of the different changing face of breast cancer has been mammography screening. Mammography is a very imperfect tool, but it did change the spectrum of patients presenting with breast cancer. We shifted historically from women coming forward when they noticed that there was a lump in their breast, or a doctor noticed that, and we could find cancers preclinical before that happened, and we really saw a shift in both the morbidity of the treatment, but also the survival.

That was a big win, but as I said it’s limited, and we have women presenting with advanced cancer despite routine screening. We have the costs and the false positives and the challenges of using mammography effectively. So I think that what I’m most excited about is changing the paradigm of how we screen and moving away from a very archaic age-based approach and moving into a risk-based approach.

Everyone has seen over the years the arguments about screening mammography. In Europe they tend to start at 50 and screen every two to three years. In the U.S. we constantly battle about whether you start at 40 or 50 and it’s every year or every two years. That argument is so limited. It’s almost unbelievable to me that we’re still having a basic argument about 40 or 50 or every year or every two years when there’s such a diversity of the risk profiles of women within their 40s, within their 30s, within their 50s, and we ignore that. Now one of the reasons why we’ve ignored it is our traditional risk models are inadequate. So the area I’m most excited about with artificial intelligence is using computer vision, not to look for cancer currently on the mammogram, but to predict whether that woman will develop cancer within the coming five years. So if you can look out into the future, is there something about this tissue that is putting this woman at increased risk? And our research to date shows that the AI applied to the basic regular mammogram can predict future breast cancer at a level that we just haven’t seen before.

It also eliminates the really unfortunate racial biases in our traditional risk models, which were built largely on European Caucasian women, and just don’t perform for us in Black, Hispanic, and Asian women. There’s a whole other domain, too, of having the computers learn how to read the mammograms, because one of the limitations of mammography is you need these highly specialized humans to read them, which really reduces the impact of screening mammography globally, because we just don’t have enough highly specialized radiologists to interpret the mammograms. So I think we’ll also see that shift.

Garraway: We could have a whole conversation, of course, on AI in medicine, and what Connie described in radiology is so exciting. It’s really going to be revolutionary. I’ll just say at a high level that AI is already changing every component of the research and development of new medicines, starting all the way from the very beginning, where you can use AI to conduct a lot of the compound screening or chemical screening in a computer. Where it used to be, you have to have lots of expensive chemical libraries and iterative screening of things. A lot of that can be done in silico, as we call it, because of AI, and even design of therapeutic antibodies from scratch, using AI-first principles. Then when you get into the clinic, the ability to synthesize all kinds of patient data to predict the kinds of patients that one should study so that you’re not fooled either in the positive or the negative way about whether a medicine is working. So it’s hard to come up with a component of the research and discovery of medicines that’s not being impacted by AI.

Laine Perfas: A lot of Connie’s work involves using AI for mammography and then Levi, you mentioned really every area of medicine is being revolutionized. Are there other emerging technologies that are really changing the landscape of cancer detection, treatment, and lowering morbidity rates?

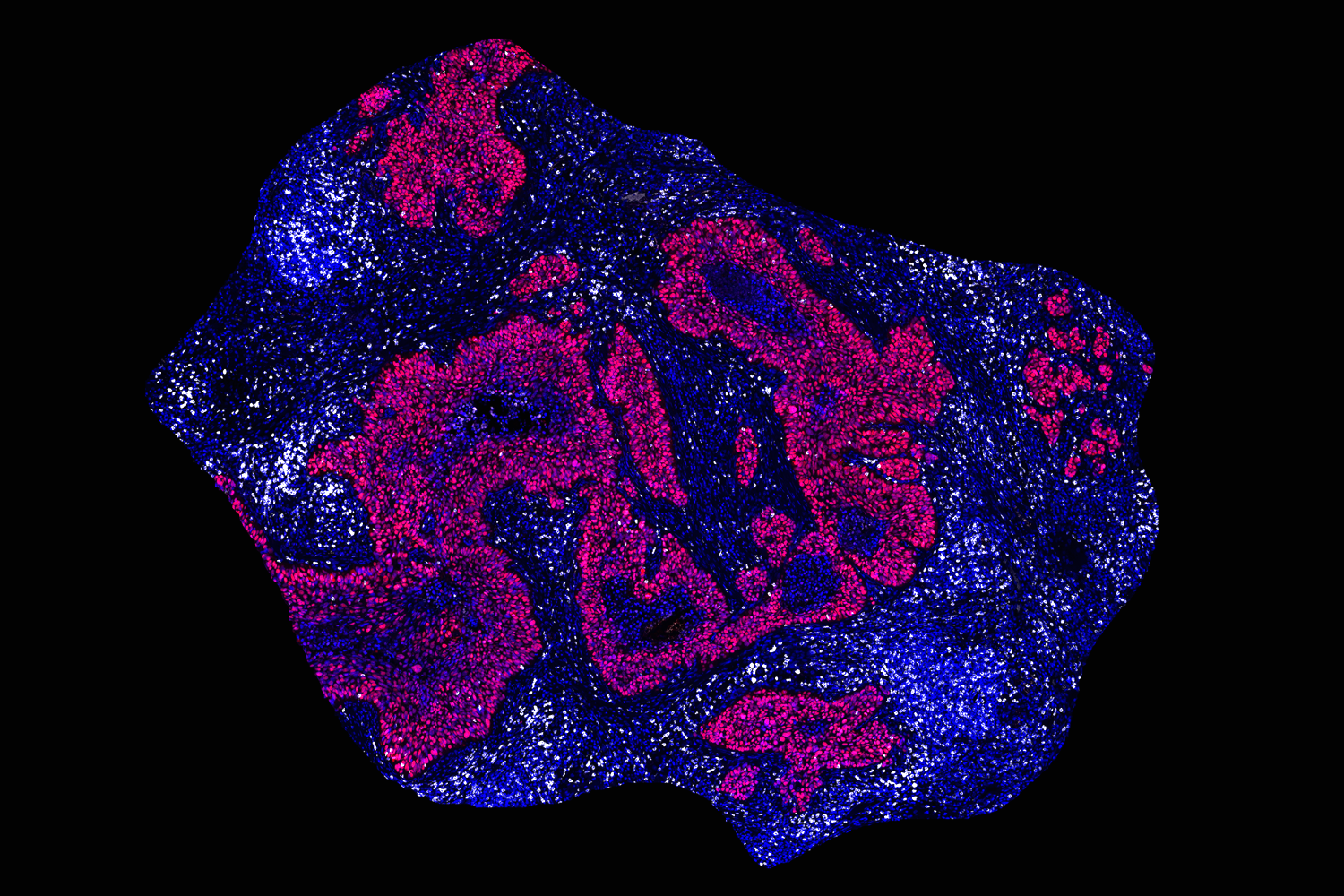

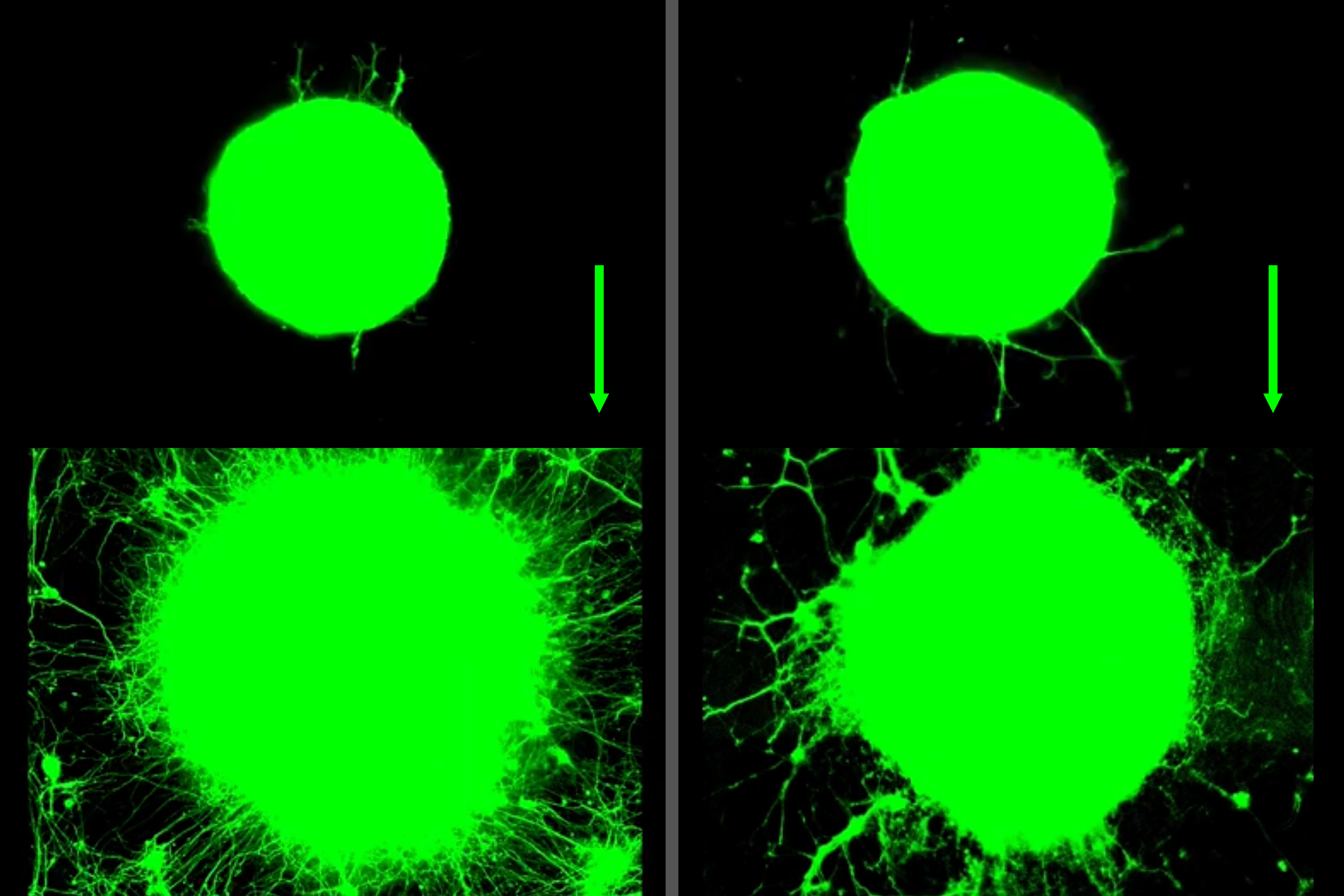

Wu: I think there’s a lot of exciting technologies that are among us right now. It’s not for nothing that we’re in the age of human biomedicine that we actually can learn directly from human biospecimens as opposed to fruit flies, worms, and mice, which is really how we gained our insights in the past. Along the lines of some of the AI work, there’s a tremendous interest, not only unlocking the secrets one cell at a time, looking at the DNA, the RNA, the protein expression, but also looking to see how all of these cells in, for example, tumor tissue, are patterned, are organized in space. These patterns on the one hand are teaching us how the cells are interacting with each other and allowing us to relate that to patient characteristics. So for patients who are destined to respond or not respond to a particular therapy, what were the patterns that were seen? And what does that tell us about the biology that happened? A lot of that information can also be fed into AI-related algorithms so that we can become better at pattern recognition.

Lehman: Yeah, Cathy, I like how you’re presenting that because it is where, again with these multidisciplinary approaches, the more I interact with specialists in computer science and artificial intelligence, the more I realize how much we really need their expertise just infusing healthcare. Because what we deal with is, we’ve had this incredible renaissance where we have so much technology that can collect so much data and in the imaging sciences alone. I think about, when I started, the kinds of images I would look at with plain films and a chest X-ray and a mammogram and then the complexity of the way that we can image the human body and the data that results from that. But the technology to collect that information, to create those patterns, just far exceeds our ability as humans. From the military, from the auto industry, I mean, what they’re doing in computer vision is just unbelievable. And bringing that into healthcare to improve the lives of our patients is incredibly exciting.

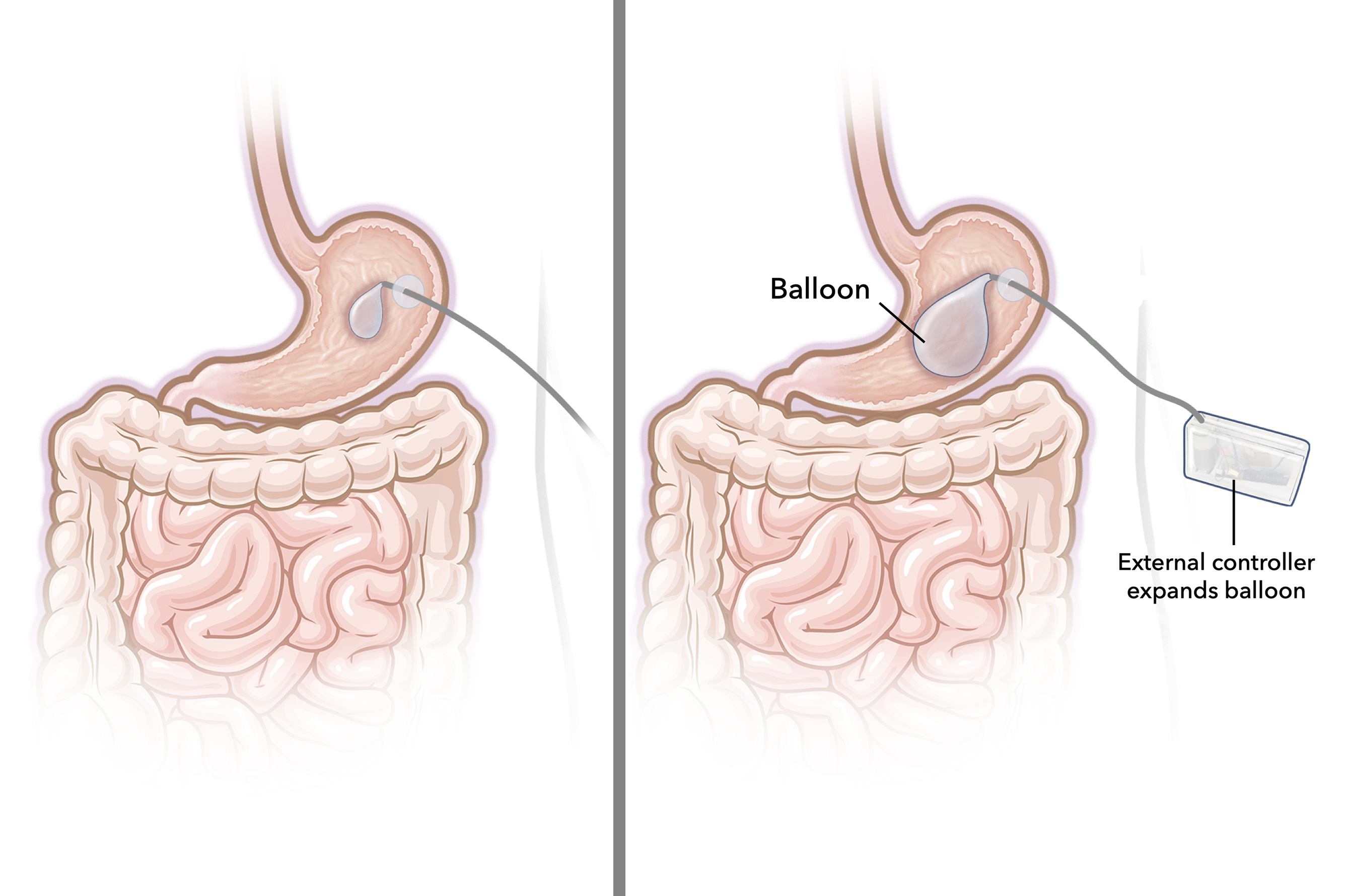

Garraway: Sam, you asked the question about other kinds of technologies. Of course, as Connie’s mentioning, AI pervades all of them, but I will mention there are technologies that are also allowing new kinds of cancer treatments to emerge. There are now what we call treatment modalities, which are different than were possible in the past. I’ll just mention a couple of them.

One is what we call cellular therapy. So this is a technology platform. You basically collect certain kinds of immune cells from an individual and then you expand them in the laboratory. You engineer them so that they can destroy tumor cells very effectively and then you give them back to patients. And so, the first generation of cell therapy, you would collect those cells from a patient with, let’s say a blood cancer, and then you engineer them and you give them back to the same patients. That actually often works remarkably well. You can get very profound clinical benefit in patients who otherwise weren’t going to benefit at all. But as you might imagine it’s logistically challenging to do this for every patient, and in every center and every context. So not as many patients have access to cell therapy as one might like.

So there’s now a new kind of emerging generation of cell therapy. The technical term is allogeneic cell therapy. In that setting, what you do is you collect immune cells from completely unrelated donors, and you expand them and you engineer them, just like we talked about, but then you can store them so that in the future, you have, like, an off-the-shelf way of leveraging this cell therapy. You don’t have to do the whole start-to-finish process on every single patient, every single time. We think this is potentially a really exciting, future promise. Then the other platform I’ll just mention very briefly, it’s called bispecific antibodies. Traditionally one kind of therapy we call a therapeutic antibody, it’s a mimic of the immune system but it allows you to design an antibody that binds a particular disease target very tightly. But bispecific antibodies work by binding not just one target, but two targets. So if one target is on the tumor cell and the other target is on the immune cell, the bispecific antibody can bring the immune cell to the tumor cell and activate the immune cell and kill the tumor cell. So I just want to bring up that we talked a lot about AI as it’s revolutionizing everything, but there are other kinds of platforms that we use more and more in the pharmaceutical arena to try to develop new kinds of medicines that can bring new kinds of benefits.

Laine Perfas: Hearing about all these emerging therapies is so exciting and amazing and miraculous-seeming, especially as someone who is not a cancer researcher. But I also want to acknowledge that there’s still challenges there, you know, there’s costs, resources, still limitations on technology. A lot of it is just a lot of work.

Wu: We know. Oh, we know.

Laine Perfas: So what keeps you all hopeful with the current trajectory and where do you see us being or hope we’ll be 10 years from now, 20 years from now?

Wu: I think the hope comes from all the progress that we see. It is incremental. I think all of us know the challenges but experience the positive signals that kind of give us hope and tell us that we’re on the right track, and you’ve got to have the focus and the vision to get you through the finish line.

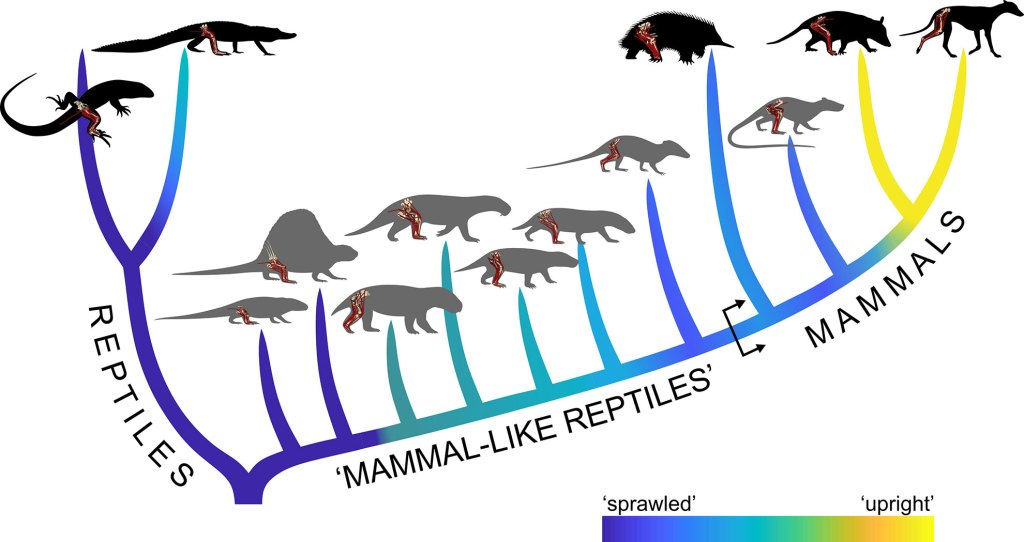

Garraway: Yeah, Sam, I think it’s a really prescient question because I know that both Connie and Cathy are part of outstanding institutions where unfortunately, the waiting rooms are still all too full with patients, some of whom are benefiting from these approaches, but others are not benefiting enough, or even at all from these approaches. So the unmet need is still quite considerable, and sometimes it feels like the pace of advance, it’s almost like, there’s a concept of how evolution happens, which is punctuated equilibrium: There’s a bunch of evolution, and then it plateaus, and there’s a bunch more, and then it plateaus. Cancer research and drug development can be like that. So you have this flurry of activity that led to targeted therapies, and then you have this flurry of activity that established immunotherapies, but all the while, you can be in these plateau phases also, where it’s like, “Oh, it’s not happening fast enough.” But the fact that these advances have happened and that we’ve been fortunate enough in our careers to either witness or, in some cases, participate in those advances, it doesn’t get old. You don’t forget those moments of impact, those opportunities to bring the advances. That’s what motivates you to bring more of those. I know for me, that’s what wakes me up in the morning.

Lehman: I actually think our strongest energy is around what we know needs to be done and the technology we have to make that happen. So we need to have the right people agree that this is the direction we have to go in. You can be in those domains where dogma, and this is the way we’ve always done it, and politics, can slow down the implementation and the progress. And so that’s really in the domain that I’m working the most in. The early detection-prevention side is to change the guidelines, to change the approach, to change how we think about how we screen to detect breast cancer early.

COVID was such a horrible period for so many, but one of the silver linings was we realized that we can be both safe and fast in certain domains of healthcare. I had been struggling with how many barriers there were to telehealth and to providing services to women in rural areas and in healthcare deserts. All of a sudden, all those barriers with COVID, it’s like, we can probably do these things that we used to always say weren’t safe, weren’t OK. But now that we need to do it, we can do it. I think it gave people new vision in what can be accomplished. That is something that’s going to be exciting as we continue to move forward in the next few years.

Laine Perfas: Thank you for this wonderful conversation.

Thanks for listening. To find a transcript of this episode and links to all of our other episodes, visit harvard.edu/thinking. This episode was hosted and produced by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was edited by Ryan Mulcahy, Simona Covel, and Paul Makishima with additional editing and production support from Sarah Lamodi. Original music and sound designed by Noel Flatt. Produced by Harvard University, copyright 2024.